ERRATUM NOTICE

Important: There has been an erratum issued for this article. Read more …

Summary

这个协议描述了从一个9周龄大鼠branchiomeric头肌卫星细胞的分离。肌肉从不同的鳃弓起源。随后,卫星细胞在局部上光毫米大小来研究其分化培养。这种方法避免了卫星细胞的扩增和传代。

Introduction

约1:500至1:1000的新生儿表现出涉及唇部和/或腭(CLP)的一个裂口;因此,这是在人类1中最常见的先天畸形。软腭肌肉是软腭的讲话,吞咽,吸吮和在运作的关键。如果软腭的裂存在时,这些肌肉异常插入腭骨的后端。

软腭上下移动讲话时,防止空气逸出通过鼻子。在上颚裂儿童没有造成这一现象被称为腭咽功能障碍2,3此控制功能。虽然治疗方案是可变的,软腭修复手术发生在儿童早期(6-36个月龄)4。软腭的异常插入肌肉可手术矫正5-7,然而,在7%的腭咽功能障碍仍然存在,以30%的的患者2,3,8-10。

骨骼肌通过卫星细胞(SCS)的作用,以再生能力是公认11,12。在肌肉损伤,旺被激活并迁移到损伤部位。然后,他们增殖,分化和融合形成新的肌纤维或修复受损的人13。静态旺表达转录因子表达Pax7 14,15,而他们的后代,增殖成肌细胞,另外表达生肌决定因子1(MyoD基因)16。分化成肌细胞开始表达肌细胞(肌细胞生成素)17。成肌细胞的终末分化的标志是形成的肌纤维,和肌特异性蛋白质如肌球蛋白重链(MyHC的)16,18的表达。

最近,一些战略已经在再生医学中用于改善四肢肌肉19-23的肌肉再生。在具体研究branchiomeric头部肌肉也很重要,因为它是最近表明,它们从其它肌肉的不同在几个方面24。与肢体肌肉相反,曾有人建议,branchiomeric头部肌肉含有较少的SCs 25,再生速度慢,并损伤26除之后形成更多的纤维结缔组织,增殖从branchiomeric头部肌肉旺还表示其它转录因子。例如,TCF21,颅面肌肉形成的转录因子中强烈表达再生头部肌肉但几乎在再生肢体肌肉25。在CLP患者的软腭肌肉通常更小,更精心组织比较正常腭肌肉27,28。慢速和快速纤维都存在于软腭肌肉但慢纤维更丰富。与此相反,裂肌含有较高比例的快速纤维,并且还减小毛细管供给与正常软腭肌肉29-31对比。快纤维更容易收缩引起的损伤31-33。伴随毛细血管供血不足也可促进纤维化34,35。手术裂闭合后36所有这些方面可能有助于软腭肌肉穷人再生。鉴于此,一个协议的branchiomeric头肌的SCs的分离和表征是关键的。这提供了研究branchiomeric头部肌肉SC生物学的可能性。此外,可以开发基于组织工程的新疗法手术中电和其他条件损害颅面区域后,以促进肌肉再生。

在一般情况下,许旺可以肌肉组织14的离解后得到。切碎,酶消化,并研磨一般都需要从它们的小生释放旺。雪旺可通过预镀上的未涂覆的菜肴14,37,38进行纯化,果actionation上珀39,40,或fluorescent-或磁性细胞分选41-43。在这里,我们提出了一个新的经济和快速的协议,用于卫星细胞从年轻的成年大鼠branchiomeric头部肌肉的隔离。这个协议是基于一个先前的原稿14,并特别适用于小的组织样本。从代表肌肉旺从第1次,2 次 ,和第 4 次鳃弓始发的分离进行说明。分离后,低数量的卫星细胞都在毫米大小的细胞外基质凝胶点来研究其分化培养。这种方法避免了对旺的膨胀和传代的要求。

Protocol

本文所述的所有实验,按照荷兰法律和法规(RU-DEC 2013-205)批准由当地局从Radboud大学奈梅亨动物实验。

1.细胞外基质凝胶点

- 隔离之前执行以下步骤之一天:

- 解冻等分试样的细胞外基质凝胶(100微升),在4℃下至少为1.5小时。稀释在Dulbecco改良的Eagle氏培养基1:10用4500毫克/升葡萄糖,4mM的L-谷氨酰胺,和110毫克/毫升丙酮酸钠(DMEM)中。保持在4℃的细胞外基质凝胶在任何时候。注:突然的温度变化会导致不均匀的涂层和晶体的形成。

- 保持在冰上的稀释细胞外基质凝胶溶液15分钟。

- 预寒意20微升微量10分钟。

- 把8孔室玻片的100毫米的培养皿和10分钟的盘转移到冷表面( 例如一个冰柜包)。

- 使用预冷微量把在各一滴10μl的细胞外基质凝胶的井。保持培养皿上冰冷的表面至少在7分钟( 图1A)。

- 完全除去剩余的细胞外基质凝胶( 图1B),并干燥该井在37℃下过夜。

头部解剖2.肌(咬肌,二腹肌和吊具膀帆)

- 解剖前,准备50毫升磷酸盐缓冲盐水(PBS)中补充有2%青霉素 - 链霉素(P / S)的。置于冰上。

- 一位年轻的成年大鼠(9周),与CO 2 / O 2的安乐死后,斩首的头部和从头部取下的皮肤。头转移到冰冷的PBS,在50毫升管补充有2%P / S。

- 咬肌(从第1鳃弓派生)

- 将头一侧上一个硅胶垫和皮下ñ修复eedles( 图2A)。

- 确定腮腺和面神经( 图2A)。揭露深筋膜覆盖腺体。切开筋膜,用剪刀切开取出腺体。确定外耳道。从茎乳孔追踪面神经并小心地用手术刀刀片第15号取出颞,颧,颊分支机构。

- 通过去除筋膜释放咬肌浅头。确定咬肌两种浅表和深部负责人。跟踪浅表头,直到上颌骨颧突插入其厚腱腱膜。

- 在颧突与直钳分开它的起源肌腱。用手术刀片15号或夹层剪刀,小心它的生活( 图2B)削减它。

- 解剖咬肌的肤浅头,直到它的角度插入和T的下半部分他侧向下颌骨的支的表面用手术刀刀片号15( 图2C)。现在,完全去除肌肉。

- 二腹肌后腹(从第二鳃弓派生)

- 将头在上的硅胶垫仰卧位置和与皮下注射针( 图3A)固定。

- 取出皮下脂肪既覆舌下和下颌下腺。接下来,除去浅筋膜,用剪刀清扫腺体。暴露二腹肌(前,后腹)。

- 抓住后腹的前肌腱采用了直板钳,剪,小心翼翼地解剖它,直到它在鼓泡( 图3B)的由来。做同样的对侧。

- 提腭帆肌(从第4个鳃弓派生)

- 二腹肌后腹的解剖后,本地化舌骨肌,横向拉,并小心地将其删除( 图4A)。

- 本地化提腭帆是在插入鼓膜泡( 图4A)的肌腱。仔细解剖,并削减其两侧。

- 寻找气管和运行背后的食道。提起食道,并露出咽,喉和软腭。

- 本地化软腭插入提腭帆所在的区域,并切断其松动( 图4B)。

注意:直接解剖后,小心地从立体显微镜下每一块肌肉肌腱删除和结缔组织。迅速浸没在乙醇70%所有的样品,并将其转移到冰冷的PBS在15毫升管补充2%P / S。

3.隔离卫星细胞

- 执行以下步骤准备从3组肌肉SC隔离:

- 准备7.5毫升0.1%链霉蛋白酶的DMEM。过滤通过0.22微米的过滤器的溶液。预温热的水浴将溶液在37℃下分离之前10分钟。

- 制备35的DMEM补充有10%马血清(HS)和1%P / S的溶液中。还预先温暖,在37℃的水浴中。

- 制备其由DMEM中补充有20%牛胎儿血清(FBS),10%HS,1%P / S和1%鸡胚提取物(CEE)15毫升培养基。在水浴中预暖在37℃。

- 预涂层6塑料移液器(10毫升)与HS和干燥使用前至少10分钟。

- 在培养罩,转移的每个肌成一个6孔板的孔中。使用解剖剪,肌肉小块约2毫米。要小心,不要讳言组织过多。

- 小心加入2.5毫升0.1%的链霉蛋白酶溶液到每个孔中并在37℃进行60分钟。经过20,40和60分钟,轻轻摇动板。注:确切的所需时n中孵育取决于如年龄的动物和应变的因素。

- 在显微镜下监视。检查肌肉片段和停止酶消化当纤维束得到松动外观( 图5)。

- 添加2.5的DMEM毫升补充有10%HS和1%P / S。转移到15毫升管和离心管,在400×g离心5分钟。弃去上清液倾析。

- 加5的10ml DMEM补充有10%HS和1%P / S。吸取的溶液上下用10毫升塑料吸管(研磨)为至少20倍以均化该组织。

- 离心管,在200×g离心4分钟。收集上清液并转移到15毫升管。

- 加5的10ml DMEM补充有10%HS和1%P / S。吸管再次用10毫升塑料吸管,直到组织碎片通过吸管传递容易。

- 离心管,在200×g离心4分钟,并收集在15ml试管上清液。

- PUT斯达康一个细胞过滤网(40微米)至50ml管中,并含有离解的细胞的上清液转移到过滤器。用1毫升的DMEM最大细胞恢复洗。

- 离心管在1000×g离心10分钟,并弃用吸管将上清液。

- 悬浮在300微升培养基中的颗粒和细胞计数在血球。

在细胞外基质凝胶点4分化卫星细胞

- 稀释细胞悬浮液,以获得1.5×10 3个细胞于10微升培养基中。

- 固定的腔室玻片用胶带盖和标记用黑色标记在对象玻璃的底侧的斑点。

- 用微量,把一滴10微升细胞悬液到细胞外基质凝胶点。检查显微镜是否细胞悬液滴已正确放置当场下。孵育六个小时,在37℃。

- 小心LY添加400μl的培养基(补充有20%胎牛血清,10%HS,1%P / S和1%CEE)的孵育三天,在37℃。

注:在这一点上,新鲜分离的SC受到大面积创伤(酶消化和苛刻的研磨),他们需要恢复。期间的前三天37.下一页不干扰细胞,培养基可根据实验的类型而改变。

细胞外基质凝胶斑点可以接种高细胞密度(1.5-2.5×10 3 /20μL)对分化测定。培养培养基(DMEM补充有20%胎牛血清,10%HS,1%P / S和1%鸡胚胎提取物)可以每三天更换。 - 另外,如果扩张和传球需要按照下面的步骤:

- 解冻等分试样的细胞外基质凝胶(500微升),在4℃下至少为1.5小时。在稀释DMEM 1:10,按照点1.1.1的建议。

- 预寒意10毫升吸管10分钟在4#176;℃。

- 转移3 T75烧瓶在冷表面( 例如一个冰柜包)10分钟。

- 使用预冷吸管把1毫升细胞外基质凝胶到每个烧瓶中。检查的表面被完全覆盖。保持瓶在冰冷的表面至少在7分钟( 图1A)。

- 完全除去用10毫升吸管剩余细胞外基质凝胶和干井,在37℃进行1小时。

- 计数后,重悬在新鲜分离的SCs在10ml培养基(DMEM补充有20%胎牛血清,10%HS,1%P / S和1%鸡胚胎提取物)中的预涂覆T75烧瓶和种子。

- 三天后,改变培养基(和每三天),直到80%汇合为止。传代,用PBS洗T75烧瓶三次。下一步加入1 ml 0.25%胰蛋白酶溶液,孵育3分钟,在37℃。重悬的9ml培养基(DMEM补充有20%胎牛血清,10%HS,1%P / S和1%鸡胚提取物)和离心机在200×g离心5分钟。弃去上清液。计数后,重悬1×10 6个细胞在1000微升培养基并冷冻的细胞。

Representative Results

使用此协议,咬肌(一侧)得到0.8-1×10 6细胞,二腹肌(后腹)得到1.5-2×10 5个细胞,并提腭帆肌产量1-1.5×10 5个细胞。细胞产率取决于肌肉类型的动物,应变和年龄。对于这三个肌肉组间比较,新鲜分离的SCs接种在相同细胞密度(1.5×10 3个/ 10微升)。直接在分离后,90%以上的新鲜分离细胞的表达表达Pax7( 图6)。

4日,7日和10文化沾满抗表达Pax7,MyoD的,肌细胞生成素和免疫MyHC的。五场任意使用每一个20X的目标培养计数。在第4天大同7和缪D被表达于所有的肌肉群( 图6和图7和8),SatCs的但是从咬肌和二腹肌后代开始EXPRES唱肌细胞生成早于提腭帆肌( 图9)。在第10天,肌细胞生成素的表达在所有组中是强烈减少( 图9)。接种在细胞外基质凝胶点之后的几天,增殖细胞开始融合,形成多核肌管,这表达肌球蛋白重链。小肌管是在第7天( 图10)清楚可见。在第10天,对肌管的抽搐可以观察到( 视频1)。

图1:细胞外基质凝胶点在玻片(A)为了便于操作,将8孔室滑动到100毫米的培养皿。每个腔室中吸取10微升细胞外基质凝胶,并把它放在冷的表面(7分)。 ( 二)外过剩矩阵G后玻片埃尔被除去。

图2:动物的侧视图咬肌剖析 ( 一 )负责人。耳(E),腮腺(P)和面神经(七)。 ( 二)咬肌(MS)和颞肌(T)的肤浅头腱肌腱膜(TE)。用镊子分离从其插入的肌腱。 (三)认真解剖肌肉,直到它的下颌骨升支插入。 E:耳,P:腮腺,VII:面神经,T:颞肌,MS:咬肌,特浅头:肌腱,熔点:咬肌深头。

图3:二腹肌后腹的夹层(。动物一)仰卧位头。本地化颌下腺(SG),咬肌(M),面神经(VII)和胸锁乳突肌(SCM)。取出颌下腺。 ( 二)本地化二腹肌前(AD)和后腹(PD)。采用了直板钳,取后腹的前肌腱,切开它,仔细解剖它,直到它在鼓泡(TY)的由来。 E:耳,SG:颌下腺,VII:面神经,M:咬肌,SMC:胸锁乳突肌,AD:前腹二腹肌,PD:后腹二腹肌,泰:鼓泡。

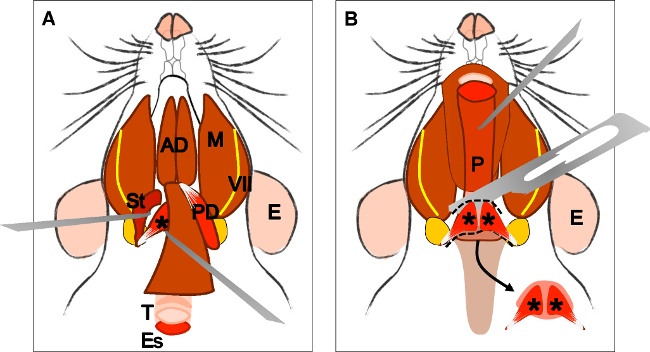

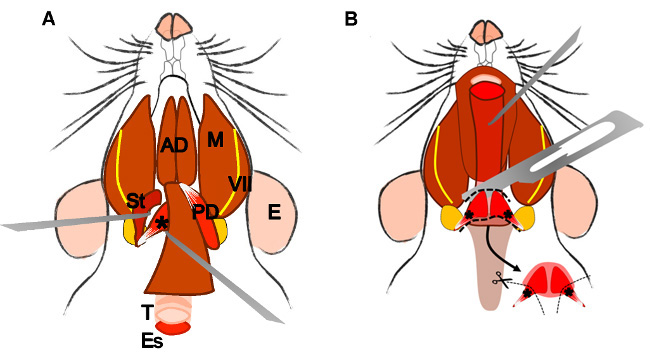

图4:上睑提腭帆肌的解剖(A)二腹肌(后腹)的解剖后,普遍的看法。舌骨肌(ST)和上睑提肌腱腭帆可以本地化。注气管(T)和食道(ES)运行它的后面。 (B)解除气管和食道咽(P)的被暴露之后。提上睑肌腭帆进入软腭的插入是现在可见。箭头指示解剖软腭与提腭帆肌肉在两侧。 E:耳,ST:舌骨肌,VII:面神经,M:咬肌,AD:前腹二腹肌,PD:后腹二腹肌,T:气管,ES:食道,P:咽部,提*腭帆肌。

图5:肌肉组织(A) 的前外观和(B)的酶消化用链霉蛋白酶后。注意,肌束出现酶消化后,以松开。

图6:大同7免疫染色新鲜分离的SCs,施加到细胞外基质凝胶在隔离结束时(初始组织消化后约6小时)。五场任意用一个10X的目标,平均每场210细胞计数。大约90%的细胞是大同7阳性。 DAPI:蓝色,表达Pax7:红色。比例尺,100微米。

图7:大同7,MyoD的免疫第4天,第7和10的培养物染色抗体表达Pax7和MyoD的免疫染色。 (A - C)和(D - F)4天的代表性显微照片和7个文化从咬肌。 (G和 H +和MyoD的+每显微镜视野核的数目进行计数,并表示为核的总数(DAPI)的百分比。 DAPI:蓝色,表达Pax7:红色,MyoD的:绿色。秤吧,100微米。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

图8:表达Pax7±/±MyoD基因分布在文化从单核细胞培养的咬肌,二腹肌和提腭帆肌(A - C)第4天,第7和第10文化沾满抗表达Pax7和MyoD的免疫染色。细胞的总数量是基于核的总数(DAPI)的。 (D)表达Pax7±/±MyoD基因的CEL量化数据LS。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

图9:肌细胞生成素的免疫染色天4,7和10的培养物染色抗肌细胞生成素。 (A - D)4天的代表性显微照片和7个文化从提腭帆肌。 (E)的肌细胞生成素+每显微镜视野核的数目进行计数,并表示为核的总数(DAPI)的百分比。 (F)数据肌细胞生成素+细胞的定量。 DAPI:蓝色,肌细胞生成素:绿色。秤吧,100微米。 请点击此处查看该FIGUR的放大版本。即

图10:球蛋白重链免疫第4天,第7和10的培养物染色抗肌球蛋白重链(MyHC的)。第4天,7的代表性显微照片,并从二腹肌(DIG)肌肉10培养物。在7天,小肌管存在,而在第10天漫长而精心组织肌管是显而易见的。秤吧,200微米。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

视频1:肌管与抽动抽动肌管两个具有代表性的领域的例子显示了从天二腹肌10文化请点击此处观看该视频。

Discussion

雪旺从不同branchiomeric头肌从一个9周龄的Wistar大鼠和对细胞外基质凝胶斑点直接分离培养无需事先膨胀和传代。分离后,将细胞计数并接种在相同细胞密度。对于三种不同的肌肉的平行隔离,这种方法需要大约4小时。为了避免培养污染,一个关键的步骤是快速清洗酒精70%的肌肉解剖后。

期间的SC隔离它切割肌肉组织切成小块(约2mm),但避免过多切碎,因为这将导致由于细胞损伤的小细胞产量是重要的。此外,酶消化的持续时间必须小心地在显微镜下检查,以避免进一步的损害。消化的目的是离解的肌纤维。因为90%以上的分离的细胞的表达表达Pax7,没有进一步纯化是必须的( 图6-8)。这避免了在其它方法,例如在未涂覆的菜肴14,37,38预镀,分馏上的Percoll 39,40额外的纯化步骤,或fluorescent-或磁性细胞分选41,43。对于研磨有必要促使组织碎片和枪头的开口之间的剪切,因为这可以使机械释放的雪旺。如果用10毫升吸管(直径尖端内:1毫米)的研磨是困难的,有5毫升(直径尖端内:2mm)的移液管可以首先使用。或者,玻璃巴斯德移液管可以在所希望的直径被切割和使用。这种方法简单,高效,允许SC从不同的肌肉样本的同时分离。

在培养板的SCs也可以涂有明胶或胶原蛋白,但我们以前的研究表明,细胞外基质凝胶是好得多的肌源性潜力的维护比胶原38。的细胞外基质凝胶斑点毫米级(10微升/ O 2毫米或20微升/Ø4 MM)允许增殖和SCS与细胞的数量有限的分化研究。为分化测定约8至20倍的细胞较少,需要相比于24孔板(直径15.6毫米),以及约80至200倍更少相比毫米至35毫米的培养皿中(直径35 MM)14,38。

由于细胞外基质凝胶是昂贵的,这种方法也更具有成本效益。此外,该室载玻片可由塑料盖来代替滑动,以进一步降低成本。为细胞外基质的凝胶的制备掩护腔室玻片过夜干燥是必不可少的。作为细胞外基质凝胶斑点是透明的,有必要使用背光来标记斑点在底侧。腔室载玻片固定在一个培养皿容易操纵。进一步的细胞培养扩张是没有必要的,它提供了学习的SMAL的雪旺的可能性LER肌肉或小的肌肉样本。可替代地, 例如 ,用于PCR或肌肉构建如果需要更多的细胞,新鲜分离的SCs可以首先在T75烧瓶如上所述扩大。

雪旺分离使用该协议不适合用于进一步纯化用分离后的流动立即术。有链霉蛋白酶消化导致表面的广泛消化抗原14。了用于细胞培养的马血清和胎牛血清首先必须正确表征隔离之前,因为不同的批号不同的影响成肌细胞增殖和分化。

在最近几年,有一种在从鳃弓和头的中胚层( 例如眼外肌)24来自肌肉的兴趣与日俱增。已经清楚地表明,头和四肢肌肉具有高度不同的特性。从旧的动物咬肌似乎重新覃它们的再生能力与四肢肌肉25,26的比较。从种姓眼外肌具有强大的增殖和分化能力堪比从头部肌肉种姓,并显示出更大的潜力植入比四肢肌肉旺24。

光纤类型分布和肌球蛋白组合物之间的肌肉群,也物种之间变化。肌肉从第一鳃弓在人类起源同时包含慢速和快速纤维(IIA亚型和IIX),新生儿肌球蛋白和肌球蛋白典型的发展中国家心肌。在这些啮齿动物的肌肉含有约95%的快速纤维肌球蛋白IIa和IIb)44-46。研究禽流感的肌肉显示,从不同的肌纤维类型不同种姓的分化能力。从快速纤维只种姓分化成快肌纤维,而从慢纤维旺能分化成两种类型的纤维47。此外,旺中快肌的百分比纤维比在慢肌纤维48,49更低。这表明,纤维型分布,必须考虑到对研究上的肌肉在颅面区域。类似的腭裂的肌肉,在啮齿动物的LVP包含几乎完全快纤维50。出于这个原因,从LVP种姓适用于腭裂的领域临床前研究。

该协议提供了新的可能性,研究从branchiomeric头部肌肉或其他肌肉更小或更小的肌肉样本得到旺。这将有利于新的疗法的开发,以改善肌肉在颌面区域中的条件的再生如腭裂而且在影响较小的肌肉的其他条件。

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Hypodermic Needle 25 G 0.5 x 25 m | BD Microlance | 300400 | |

| Dissecting scissors | Braun | BC154R | |

| Micro forceps straight | Braun | BD330R | |

| Surgical Scalpel Blade No. 15 | Swann-Morton | 0205 | |

| Alcohol 70% | Denteck | 2,010,005 | |

| Permanox Slide, 8 Chamber | Thermo Scientific | 177445 | |

| 6 well cell culture plate | Greiner bio-one | 657160 | |

| Cell Culture Dishes (100 x 20 mm) | Greiner bio-one | 664160 | |

| 15 ml sterile conical centrifuge tube | BD Biosciences | 352097 | |

| 50 ml sterile conical centrifuge tube | BD Biosciences | 352098 | |

| Cell strainer (40 μm) | Gibco | 431750 | |

| 10 ml serological pipette | Greiner bio-one | 607180 | |

| 20 µl FT20 | Greiner bio-one | 774288 | |

| Matrigel, Phenol-Red Free | BD Biosciences | 356237 | 10 ml |

| Pronase | Calbiochem | 53702 | 10 KU |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline | Gibco | 14190-144 | 500 ml |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium, high glucose, GlutaMAX Supplement, pyruvate | Gibco | 10569-010 | 500 ml |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Fisher Scientific | 3600511 | 500 ml |

| Horse Serum | Gibco | 26050088 | 500 ml |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin (10,000 U/ml) | Gibco | 15140-122 | 100 ml |

| Chicken Embryo Extract | MP Biomedicals | 2850145 | 20 ml |

References

- Gritli-Linde, A. Molecular control of secondary palate development. Developmental Biology. 301, 309-326 (2007).

- Marrinan, E. M., LaBrie, R. A., Mulliken, J. B. Velopharyngeal function in nonsyndromic cleft palate: relevance of surgical technique, age at repair, and cleft type. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 35, 95-100 (1998).

- Morris, H. L. Velopharyngeal competence and primary cleft palate surgery, 1960-1971: a critical review. The Cleft Palate Journal. 10, 62-71 (1973).

- Mossey, P. A., Little, J., Munger, R. G., Dixon, M. J., Shaw, W. C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. 374, 1773-1785 (2009).

- Boorman, J. G., Sommerlad, B. C. Musculus uvulae and levator palati: their anatomical and functional relationship in velopharyngeal closure. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 38, 333-338 (1985).

- Bae, Y. C., Kim, J. H., Lee, J., Hwang, S. M., Kim, S. S. Comparative study of the extent of palatal lengthening by different methods. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 48, 359-362 (2002).

- Braithwaite, F., Maurice, D. G. The importance of the levator palati muscle in cleft palate closure. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 21, 60-62 (1968).

- Inman, D. S., Thomas, P., Hodgkinson, P. D., Reid, C. A. Oro-nasal fistula development and velopharyngeal insufficiency following primary cleft palate surgery--an audit of 148 children born between 1985 and 1997. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 58, 1051-1054 (2005).

- Phua, Y. S., de Chalain, T. Incidence of oronasal fistulae and velopharyngeal insufficiency after cleft palate repair: an audit of 211 children born between 1990 and 2004. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 45, 172-178 (1990).

- Kirschner, R. E., et al. Cleft-palate repair by modified Furlow double-opposing Z-plasty: the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 104, 1998-2010 (1999).

- Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 9, 493-495 (1961).

- Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: still young and fascinating at 50. The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 59, 1041-1059 (2011).

- Ten Broek, R. W., Grefte, S., Von den Hoff, J. W. Regulatory factors and cell populations involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 224, 7-16 (2010).

- Danoviz, M. E., Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Skeletal muscle satellite cells: background and methods for isolation and analysis in a primary culture system. Methods in Molecular Biology. 798, 21-52 (2012).

- Seale, P., et al. Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. Cell. 102, 777-786 (2000).

- Yablonka-Reuveni, Z., et al. The transition from proliferation to differentiation is delayed in satellite cells from mice lacking MyoD. Developmental Biology. 210, 440-455 (1999).

- Zammit, P. S., Partridge, T. A., Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold. The Journal of Histochemistry And Cytochemistry. 54, 1177-1191 (2006).

- Andres, V., Walsh, K. Myogenin expression, cell cycle withdrawal, and phenotypic differentiation are temporally separable events that precede cell fusion upon myogenesis. The Journal of Cell Biology. 132, 657-666 (1996).

- Fukushima, K., et al. The use of an antifibrosis agent to improve muscle recovery after laceration. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 29, 394-402 (2001).

- Grefte, S., Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M., Torensma, R., Von den Hoff, J. W. Skeletal muscle fibrosis: the effect of stromal-derived factor-1α-loaded collagen scaffolds. Regenerative Medicine. 5, 737-747 (2010).

- Jackson, W. M., Nesti, L. J., Tuan, R. S. Potential therapeutic applications of muscle-derived mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 10, 505-517 (2010).

- Sato, K., et al. Improvement of muscle healing through enhancement of muscle regeneration and prevention of fibrosis. Muscle, & Nerve. 28, 365-372 (2003).

- Tatsumi, R., Anderson, J. E., Nevoret, C. J., Halevy, O., Allen, R. E. HGF/SF is present in normal adult skeletal muscle and is capable of activating satellite cells. Developmental Biology. 194, 114-128 (1998).

- Stuelsatz, P., et al. Extraocular muscle satellite cells are high performance myo-engines retaining efficient regenerative capacity in dystrophin deficiency. Developmental biology. , (2014).

- Ono, Y., Boldrin, L., Knopp, P., Morgan, J. E., Zammit, P. S. Muscle satellite cells are a functionally heterogeneous population in both somite-derived and branchiomeric muscles. Developmental Biology. 337, 29-41 (2010).

- Pavlath, G. K., et al. Heterogeneity among muscle precursor cells in adult skeletal muscles with differing regenerative capacities. Developmental Dynamics. 212, 495-508 (1998).

- Koo, S. H., Cunningham, M. C., Arabshahi, B., Gruss, J. S., Grant, J. H. 3rd The transforming growth factor-beta 3 knock-out mouse: an animal model for cleft palate. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 108, 938-948 (2001).

- Fara, M., Brousilova, M. Experiences with early closure of velum and later closure of hard palate. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 44, 134-141 (1969).

- Lindman, R., Paulin, G., Stal, P. S. Morphological characterization of the levator veli palatini muscle in children born with cleft palates. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 38, 438-448 (2001).

- Hanes, M. C., et al. Contractile properties of single permeabilized muscle fibers from congenital cleft palates and normal palates of Spanish goats. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 119, 1685-1694 (2007).

- Rader, E. P., et al. Contraction-induced injury to single permeabilized muscle fibers from normal and congenitally-clefted goat palates. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 44, 216-222 (2007).

- Rader, E. P., et al. Effect of cleft palate repair on the susceptibility to contraction-induced injury of single permeabilized muscle fibers from congenitally-clefted goat palates. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 45, 113-120 (2008).

- Macpherson, P. C., Dennis, R. G., Faulkner, J. A. Sarcomere dynamics and contraction-induced injury to maximally activated single muscle fibres from soleus muscles of rats. The Journal of Physiology. 500 (Pt 2), 523-533 (1997).

- Koch, K. H., Grzonka, M. A., Koch, J. The pathology of the velopharyngeal musculature in cleft palates). Annals of Anatomy. 181, 123-126 (1999).

- Fara, M., Dvorak, J. Abnormal anatomy of the muscles of palatopharyngeal closure in cleft palates: anatomical and surgical considerations based on the autopsies of 18 unoperated cleft palates. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 46, 488-497 (1970).

- Carvajal Monroy, P. L., Grefte, S., Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M., Wagener, F. A., Von den Hoff, J. W. Strategies to Improve Regeneration of the Soft Palate Muscles After Cleft Palate Repair. Tissue Engineering. Part B, Reviews. , (2012).

- Grefte, S., Kuijpers, M. A., Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M., Torensma, R., Von den Hoff, J. W. Myogenic capacity of muscle progenitor cells from head and limb muscles. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 120, 38-45 (2012).

- Grefte, S., Vullinghs, S., Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M., Torensma, R., Von den Hoff, J. W. Matrigel but not collagen I, maintains the differentiation capacity of muscle derived cells in vitro. Biomedical Materials. 7, 055004 (2012).

- Kastner, S., Elias, M. C., Rivera, A. J., Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Gene expression patterns of the fibroblast growth factors and their receptors during myogenesis of rat satellite cells. The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 48, 1079-1096 (2000).

- Yablonka-Reuveni, Z., Quinn, L. S., Nameroff, M. Isolation and clonal analysis of satellite cells from chicken pectoralis muscle. Developmental Biology. 119, 252-259 (1987).

- Sherwood, R. I., et al. Isolation of adult mouse myogenic progenitors: functional heterogeneity of cells within and engrafting skeletal muscle. Cell. 119, 543-554 (2004).

- Gilbert, P. M., et al. Substrate elasticity regulates skeletal muscle stem cell self-renewal in culture. Science. 329, 1078-1081 (2010).

- Motohashi, N., Asakura, Y., Asakura, A. Isolation culture, and transplantation of muscle satellite cells. Journal of Visualized Experiments. , (2014).

- Sciote, J. J., Horton, M. J., Rowlerson, A. M., Link, J. Specialized cranial muscles: how different are they from limb and abdominal muscles. Cells, Tissues, Organs. 174, 73-86 (2003).

- Rowlerson, A., Mascarello, F., Veggetti, A., Carpene, E. The fibre-type composition of the first branchial arch muscles in Carnivora and Primates. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 4, 443-472 (1983).

- Muller, J., et al. Comparative evolution of muscular dystrophy in diaphragm, gastrocnemius and masseter muscles from old male mdx mice. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 22, 133-139 (2001).

- Feldman, J. L., Stockdale, F. E. Skeletal muscle satellite cell diversity: satellite cells form fibers of different types in cell culture. Developmental Biology. 143, 320-334 (1991).

- Schmalbruch, H., Hellhammer, U. The number of nuclei in adult rat muscles with special reference to satellite cells. The Anatomical Record. 189, 169-175 (1977).

- Gibson, M. C., Schultz, E. The distribution of satellite cells and their relationship to specific fiber types in soleus and extensor digitorum longus muscles. The Anatomical Record. 202, 329-337 (1982).

- Carvajal Monroy, P. L., et al. A rat model for muscle regeneration in the soft palate. PloS One. 8, e59193 (2013).

Tags

发育生物学,第101,头部肌肉,提腭帆肌,二腹肌,咬肌,卫星细胞,分离原代细胞,腭裂,再生医学,组织工程,干细胞,分化,肌纤维Erratum

Formal Correction: Erratum: Isolation and Characterization of Satellite Cells from Rat Head Branchiomeric Muscles

Posted by JoVE Editors on 10/01/2015.

Citeable Link.

An erratum was issue for Isolation and Characterization of Satellite Cells from Rat Head Branchiomeric Muscles. The fourth figure was updated to explain the isolation of the LVP better.

Steps 2.5.3 and 2.5.4 were updated from:

2.5.3. Look for the trachea and the esophagus that runs behind it. Lift the esophagus, and expose the pharynx, larynx and the soft palate.

2.5.4. Localize the area of the soft palate where the levator veli palatini is inserted and cut it loose (Figure 4B).

to

2.5.3. Look for the trachea and the esophagus that runs behind it. Lift the esophagus, and expose the pharynx and the larynx.

2.5.4 Localize and dissect the area of the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. Identify the levator veli palatini and cut it at both sides (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 and its legend were updated from:

Figure 4: Dissection of the levator veli palatini muscle. (A) General view after dissection of the digastric muscle (posterior belly). Stylohyoid muscle (St) and tendon of the levator veli palatini can be localized. Note the trachea (T) and esophagus (Es) running behind it. (B) After lifting the trachea and the esophagus the pharynx (P) is exposed. The insertion of the levator veli palatini into the soft palate is now visible. The arrow indicates the dissected soft palate with the levator veli palatini muscles at both sides. E: ear, St: stylohyoid muscle, VII: facial nerve, M: masseter muscle, AD: anterior belly digastric muscle, PD: posterior belly digastric muscle, T: trachea, Es: esophagus, P: Pharynx, *levator veli palatini muscle.

to

Figure 4: Dissection of the levator veli palatini muscle. (A) General view after dissection of the digastric muscle (posterior belly). Stylohyoid muscle (St) and tendon of the levator veli palatini can be localized. Note the trachea (T) and esophagus (Es) running behind it. (B) After lifting the trachea and the esophagus the pharynx (P) is exposed. The levator veli palatini that runs laterally towards the soft palate is now visible. The arrow indicates the dissected superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle; note the levator veli palatini muscles at both sides. E: ear, St: stylohyoid muscle, VII: facial nerve, M: masseter muscle, AD: anterior belly digastric muscle, PD: posterior belly digastric muscle, T: trachea, Es: esophagus, P: Pharynx, *levator veli palatini muscle.