Abstract

An erratum was issued for Research and Development of High-performance Explosives. The abstract, introduction, protocol, representative results, and acknowledgments sections were updated.

The Abstract was updated from:

Developmental testing of high explosives for military applications involves small-scale formulation, safety testing, and finally detonation performance tests to verify theoretical calculations. small-scale For newly developed formulations, the process begins with small-scale mixes, thermal testing, and impact and friction sensitivity. Only then do subsequent larger scale formulations proceed to detonation testing, which will be covered in this paper. Recent advances in characterization techniques have led to unparalleled precision in the characterization of early-time evolution of detonations. The new technique of photo-Doppler velocimetry (PDV) for the measurement of detonation pressure and velocity will be shared and compared with traditional fiber-optic detonation velocity and plate-dent calculation of detonation pressure. In particular, the role of aluminum in explosive formulations will be discussed. Recent developments led to the development of explosive formulations that result in reaction of aluminum very early in the detonation product expansion. This enhanced reaction leads to changes in the detonation velocity and pressure due to reaction of the aluminum with oxygen in the expanding gas products.

to:

Developmental testing of high explosives for military applications involves small-scale formulation, safety testing, and finally detonation performance tests to verify theoretical calculations. For newly developed formulations, the process begins with small-scale mixes, thermal testing, and impact and friction sensitivity. Only then do subsequent larger scale formulations proceed to detonation testing, which will be covered in this paper. Recent advances in characterization techniques have led to unparalleled precision in the characterization of early-time evolution of detonations. The new technique of Photonic Doppler Velocimetry (PDV) for the measurement of detonation pressure will be shared and compared with traditional fiber-optic detonation velocity and plate-dent calculation of detonation pressure. In particular, the role of aluminum in explosive formulations will be discussed. Recent developments led to the development of explosive formulations that result in reaction of aluminum very early in the detonation product expansion. This enhanced reaction leads to changes in the detonation velocity and pressure due to reaction of the aluminum with oxygen in the expanding gas products.

The Introduction's second to last paragraph was updated from:

In order to calculate the CJ pressure of a new explosive, a PDV system can be used to measure the particle velocity between the explosive and a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) window. A very thin foil, usually aluminum or copper, is placed at this interface to act as a reflective surface. In these studies, copper was used. This foil should be thin enough to prevent significant shock wave attenuation while being thick enough to prevent detonation light from passing through. Typically, a foil thickness of 1,000 angstroms is ideal for most experimental setups. Given the particle velocity in the PMMA and the detonation velocity of the explosive, the detonation pressure can be calculated with Hugoniot shock matching equations.6

to:

In order to calculate the CJ pressure of a new explosive, a PDV system can be used to measure the particle velocity between the explosive and a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) window. A very thin foil, usually aluminum or copper, is placed at this interface to act as a reflective surface. This foil should be thin enough to prevent significant shock wave attenuation while being thick enough to prevent detonation light from passing through. Typically, a foil thickness of 1,000 angstroms is ideal for most experimental setups. Given the particle velocity in the PMMA and the detonation velocity of the explosive, the detonation pressure can be calculated with Hugoniot shock matching equations.6

Step 2.1 in the Protocol was updated from:

Machine a PMMA window sized to the diameter of the explosive charge approximately 6.5mm thick. Ensure that the window is optically clear and free of any machining defects. To accomplish this take an optically clear sheet of cast acrylic and machining out the disks using a laser cutter or similar machining process. Then, utilize water jets to obtain an optically clear surface.

to:

Machine a PMMA window sized to the diameter of the explosive charge approximately 6.5mm thick. Ensure that the window is optically clear and free of any machining defects. To accomplish this take an optically clear sheet of cast acrylic and machining out the disks using a laser cutter or similar machining process. Then, polish the PMMA to obtain an optically clear surface.

In the Representative Results Figure 3's capation was updated from:

Figure 3. PDV setup (close view). The PDV setup at the base where the flyer plate is located.

to:

Figure 3. PDV setup (close view). The PDV setup at the base.

In the Representative Results, the paragraph between table 1 and figure 7 has been updated from:

The output from the PDV trace of the flyer plate from the bottom of the explosive charge of Figures 2-3 is shown in Figure 7. The oscillations arise from the ringing in the plate from the rapid acceleration to nearly 4-5 km/sec. The CJ pressure is calculated from modeling the product gas Hugoniot with Cooper’s approximation,6 and then extrapolating the CJ point once the aluminum-explosive Hugoniot is matched. A typical screen print from such a calculation is shown in Figure 8. The technique still has some limitations since the calculations assume a linear acceleration extrapolation from the beginning of the flyer velocity. This results in slightly underestimating the pressure, as evidenced by the results (Table 1). Work is ongoing to develop new equations to fit the early acceleration of the flyer plate.

to:

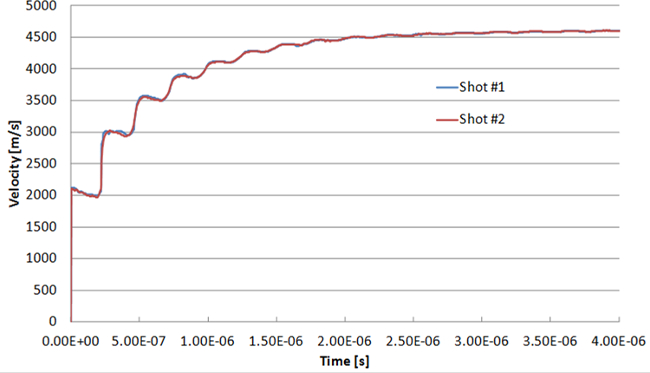

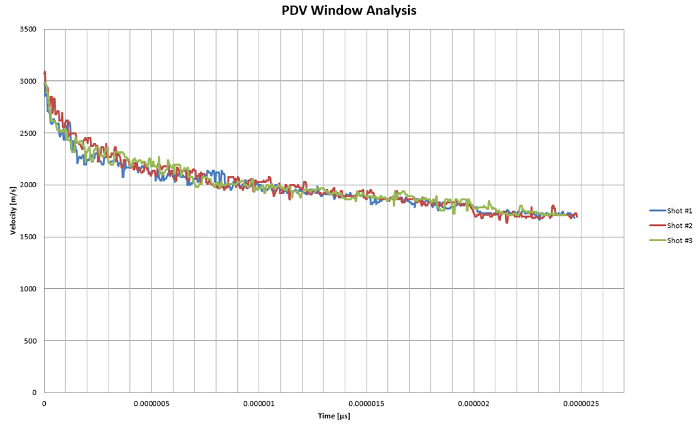

The output of the PDV trace from the bottom of the explosive charge of Figures 2-3 is shown in Figure 7. The CJ pressure is calculated from modeling the product gas Hugoniot with Cooper’s approximation,6 and then extrapolating the CJ point once the PMMA-explosive Hugoniot is matched. A typical screen print from such a calculation is shown in Figure 8. The technique still has some limitations since the calculations assume a linear extrapolation from the beginning of the window velocity trace. This results in slightly underestimating the pressure, as evidenced by the results (Table 1).

In the Representative Results Figure 7 and its caption were updated from:

Figure 7. Plate velocity as a function of time for the measurement of CJ pressure in the PBXN-5 explosive. Note the excellent agreement between two different shots, where the traces practically fall on one another.

to:

Figure 7. Window velocity as a function of time for the measurement of CJ pressure. Note the excellent agreement between the different shots, where the traces practically fall on one another.

Also in the Representative Results, Figure 8 had its caption update from:

Figure 8. Calculation of the CJ pressure from the copper flyer plate data on the PDV experiment. Note that the extrapolation assumes a linear acceleration in the initial push of the flyer plate which currently leads to an underestimation of the CJ pressure.

to:

Figure 8. Calculation of the CJ pressure from the PDV experiment. Note that the extrapolation assumes a linear acceleration in the initial push of the window which currently leads to an underestimation of the CJ pressure.

The Acknowledgments section was updated from:

The authors would like to thank the Future Requirement of Enhanced Energetics for Decisive Munitions (FREEDM) Program for funding, Mike VanDeWal and Gerard Gillen for their assistance in testing, Paula Cook for formulations assistance, and Ralph Acevedo and Brian Travers for pressing of the samples.

to:

The authors would like to thank the Future Requirement of Enhanced Energetics for Decisive Munitions (FREEDM) Program for funding, Mike Van De Waal and Gerard Gillen for their assistance in testing, Paula Cook for formulations assistance, and Ralph Acevedo and Brian Travers for pressing of the samples.

Protocol

An erratum was issued for Research and Development of High-performance Explosives. The abstract, introduction, protocol, representative results, and acknowledgments sections were updated.

The Abstract was updated from:

Developmental testing of high explosives for military applications involves small-scale formulation, safety testing, and finally detonation performance tests to verify theoretical calculations. small-scale For newly developed formulations, the process begins with small-scale mixes, thermal testing, and impact and friction sensitivity. Only then do subsequent larger scale formulations proceed to detonation testing, which will be covered in this paper. Recent advances in characterization techniques have led to unparalleled precision in the characterization of early-time evolution of detonations. The new technique of photo-Doppler velocimetry (PDV) for the measurement of detonation pressure and velocity will be shared and compared with traditional fiber-optic detonation velocity and plate-dent calculation of detonation pressure. In particular, the role of aluminum in explosive formulations will be discussed. Recent developments led to the development of explosive formulations that result in reaction of aluminum very early in the detonation product expansion. This enhanced reaction leads to changes in the detonation velocity and pressure due to reaction of the aluminum with oxygen in the expanding gas products.

to:

Developmental testing of high explosives for military applications involves small-scale formulation, safety testing, and finally detonation performance tests to verify theoretical calculations. For newly developed formulations, the process begins with small-scale mixes, thermal testing, and impact and friction sensitivity. Only then do subsequent larger scale formulations proceed to detonation testing, which will be covered in this paper. Recent advances in characterization techniques have led to unparalleled precision in the characterization of early-time evolution of detonations. The new technique of Photonic Doppler Velocimetry (PDV) for the measurement of detonation pressure will be shared and compared with traditional fiber-optic detonation velocity and plate-dent calculation of detonation pressure. In particular, the role of aluminum in explosive formulations will be discussed. Recent developments led to the development of explosive formulations that result in reaction of aluminum very early in the detonation product expansion. This enhanced reaction leads to changes in the detonation velocity and pressure due to reaction of the aluminum with oxygen in the expanding gas products.

The Introduction's second to last paragraph was updated from:

In order to calculate the CJ pressure of a new explosive, a PDV system can be used to measure the particle velocity between the explosive and a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) window. A very thin foil, usually aluminum or copper, is placed at this interface to act as a reflective surface. In these studies, copper was used. This foil should be thin enough to prevent significant shock wave attenuation while being thick enough to prevent detonation light from passing through. Typically, a foil thickness of 1,000 angstroms is ideal for most experimental setups. Given the particle velocity in the PMMA and the detonation velocity of the explosive, the detonation pressure can be calculated with Hugoniot shock matching equations.6

to:

In order to calculate the CJ pressure of a new explosive, a PDV system can be used to measure the particle velocity between the explosive and a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) window. A very thin foil, usually aluminum or copper, is placed at this interface to act as a reflective surface. This foil should be thin enough to prevent significant shock wave attenuation while being thick enough to prevent detonation light from passing through. Typically, a foil thickness of 1,000 angstroms is ideal for most experimental setups. Given the particle velocity in the PMMA and the detonation velocity of the explosive, the detonation pressure can be calculated with Hugoniot shock matching equations.6

Step 2.1 in the Protocol was updated from:

Machine a PMMA window sized to the diameter of the explosive charge approximately 6.5mm thick. Ensure that the window is optically clear and free of any machining defects. To accomplish this take an optically clear sheet of cast acrylic and machining out the disks using a laser cutter or similar machining process. Then, utilize water jets to obtain an optically clear surface.

to:

Machine a PMMA window sized to the diameter of the explosive charge approximately 6.5mm thick. Ensure that the window is optically clear and free of any machining defects. To accomplish this take an optically clear sheet of cast acrylic and machining out the disks using a laser cutter or similar machining process. Then, polish the PMMA to obtain an optically clear surface.

In the Representative Results Figure 3's capation was updated from:

Figure 3. PDV setup (close view). The PDV setup at the base where the flyer plate is located.

to:

Figure 3. PDV setup (close view). The PDV setup at the base.

In the Representative Results, the paragraph between table 1 and figure 7 has been updated from:

The output from the PDV trace of the flyer plate from the bottom of the explosive charge of Figures 2-3 is shown in Figure 7. The oscillations arise from the ringing in the plate from the rapid acceleration to nearly 4-5 km/sec. The CJ pressure is calculated from modeling the product gas Hugoniot with Cooper’s approximation,6 and then extrapolating the CJ point once the aluminum-explosive Hugoniot is matched. A typical screen print from such a calculation is shown in Figure 8. The technique still has some limitations since the calculations assume a linear acceleration extrapolation from the beginning of the flyer velocity. This results in slightly underestimating the pressure, as evidenced by the results (Table 1). Work is ongoing to develop new equations to fit the early acceleration of the flyer plate.

to:

The output of the PDV trace from the bottom of the explosive charge of Figures 2-3 is shown in Figure 7. The CJ pressure is calculated from modeling the product gas Hugoniot with Cooper’s approximation,6 and then extrapolating the CJ point once the PMMA-explosive Hugoniot is matched. A typical screen print from such a calculation is shown in Figure 8. The technique still has some limitations since the calculations assume a linear extrapolation from the beginning of the window velocity trace. This results in slightly underestimating the pressure, as evidenced by the results (Table 1).

In the Representative Results Figure 7 and its caption were updated from:

Figure 7. Plate velocity as a function of time for the measurement of CJ pressure in the PBXN-5 explosive. Note the excellent agreement between two different shots, where the traces practically fall on one another.

to:

Figure 7. Window velocity as a function of time for the measurement of CJ pressure. Note the excellent agreement between the different shots, where the traces practically fall on one another.

Also in the Representative Results, Figure 8 had its caption update from:

Figure 8. Calculation of the CJ pressure from the copper flyer plate data on the PDV experiment. Note that the extrapolation assumes a linear acceleration in the initial push of the flyer plate which currently leads to an underestimation of the CJ pressure.

to:

Figure 8. Calculation of the CJ pressure from the PDV experiment. Note that the extrapolation assumes a linear acceleration in the initial push of the window which currently leads to an underestimation of the CJ pressure.

The Acknowledgments section was updated from:

The authors would like to thank the Future Requirement of Enhanced Energetics for Decisive Munitions (FREEDM) Program for funding, Mike VanDeWal and Gerard Gillen for their assistance in testing, Paula Cook for formulations assistance, and Ralph Acevedo and Brian Travers for pressing of the samples.

to:

The authors would like to thank the Future Requirement of Enhanced Energetics for Decisive Munitions (FREEDM) Program for funding, Mike Van De Waal and Gerard Gillen for their assistance in testing, Paula Cook for formulations assistance, and Ralph Acevedo and Brian Travers for pressing of the samples.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest declared.