8.4:

אנרגיית יינון

8.4:

אנרגיית יינון

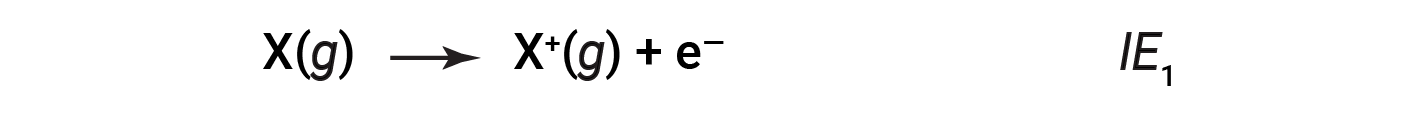

The amount of energy required to remove the most loosely bound electron from a gaseous atom in its ground state is called its first ionization energy (IE1). The first ionization energy for an element, X, is the energy required to form a cation with 1+ charge:

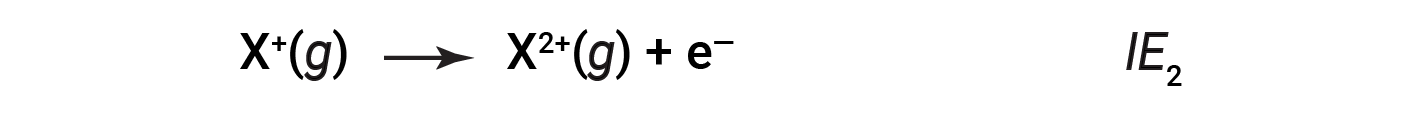

The energy required to remove the second most loosely bound electron is called the second ionization energy (IE2).

The energy required to remove the third electron is the third ionization energy, and so on. Energy is always required to remove electrons from atoms or ions, so ionization processes are endothermic and IE values are always positive. For larger atoms, the most loosely bound electron is located farther from the nucleus and so is easier to remove. Thus, as size (atomic radius) increases, the ionization energy should decrease.

Within a period, the IE1 generally increases with increasing Z. Down a group, the IE1 value generally decreases with increasing Z. There are some systematic deviations from this trend, however. Note that the ionization energy of boron (atomic number 5) is less than that of beryllium (atomic number 4) even though the nuclear charge of boron is greater by one proton. This can be explained because the energy of the subshells increases as l increases, due to penetration and shielding. Within any one shell, the s electrons are lower in energy than the p electrons. This means that an s electron is harder to remove from an atom than a p electron in the same shell. The electron removed during the ionization of beryllium ([He]2s2) is an s electron, whereas the electron removed during the ionization of boron ([He]2s22p1) is a p electron; this results in lower first ionization energy for boron, even though its nuclear charge is greater by one proton. Thus, we see a small deviation from the predicted trend occurring each time a new subshell begins.

Another deviation occurs as orbitals become more than one-half filled. The first ionization energy for oxygen is slightly less than that for nitrogen, despite the trend in increasing IE1 values across a period. For oxygen, removing one electron will eliminate the electron-electron repulsion caused by pairing the electrons in the 2p orbital and will result in a half-filled orbital (which is energetically favorable). Analogous changes occur in succeeding periods.

Removing an electron from a cation is more difficult than removing an electron from a neutral atom because of the greater electrostatic attraction to the cation. Likewise, removing an electron from a cation with a higher positive charge is more difficult than removing an electron from an ion with a lower charge. Thus, successive ionization energies for one element always increase. As seen in Table 1, there is a large increase in the ionization energies for each element. This jump corresponds to the removal of the core electrons, which are harder to remove than the valence electrons. For example, Sc and Ga both have three valence electrons, so the rapid increase in ionization energy occurs after the third ionization.

Table 1: Successive Ionization Energies for Selected Elements (kJ/mol)

| Element | IE1 | IE2 | IE3 | IE4 | IE5 | IE6 | IE7 |

| K | 418.8 | 3051.8 | 4419.6 | 5876.9 | 7975.5 | 9590.6 | 11343 |

| Ca | 589.8 | 1145.4 | 4912.4 | 6490.6 | 8153.0 | 10495.7 | 12272.9 |

| Sc | 633.1 | 1235.0 | 2388.7 | 7090.6 | 8842.9 | 10679.0 | 13315.0 |

| Ga | 578.8 | 1979.4 | 2964.6 | 6180 | 8298.7 | 10873.9 | 13594.8 |

| Ge | 762.2 | 1537.5 | 3302.1 | 4410.6 | 9021.4 | Not available | Not available |

| As | 944.5 | 1793.6 | 2735.5 | 4836.8 | 6042.9 | 12311.5 | Not available |

This text is adapted from OpenStax Chemistry 2e, Section 6.5: Periodic Variations in Element Properties.