10.5:

Relating Angular And Linear Quantities – I

All the linear motion variables have a counterpart in rotational motion. Consider a ball tied to a string of length r, rotating such that the axis of rotation lies in the plane perpendicular to its plane of motion.

When the ball changes its angular displacement by θ, the linear distance it travels is equal to the arc length s.

At any point during the motion, the linear distance is directly proportional to the angular distance θ. For 2π changes in angular distance, the corresponding arc length is 2π times the radius.

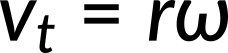

Now, take the time derivative of the equation. As the radius of the circle is constant, the rate of change of arc length is proportional to the rate of change of angular displacement. Thus, a relationship between instantaneous linear velocity and instantaneous angular velocity is obtained.

The direction of the velocity of the ball is tangential to the circular motion, hence termed as tangential velocity.

10.5:

Relating Angular And Linear Quantities – I

If the rotational definitions are compared with the definitions of linear kinematic variables from motion along a straight line and motion in two and three dimensions, we can observe a mapping of the linear variables to the rotational ones.

When comparing the linear and rotational variables individually, the linear variable of position has physical units of meters, whereas the angular position variable has dimensionless units of radians, as it is the ratio of two lengths. The linear velocity has units of m/s, and its counterpart, the angular velocity, has units of rad/s.

In the case of circular motion, the linear tangential speed of a particle at a radius r from the axis of rotation is related to the angular velocity by the relation

This could also apply to points on a rigid body rotating about a fixed axis. Here, only circular motion is considered. In a circular motion, both uniform and nonuniform, there exists a centripetal acceleration. The centripetal acceleration vector points inward from the particle executing circular motion toward the axis of rotation.

Thus, in a uniform circular motion, when the angular velocity is constant and the angular acceleration is zero, we observe a linear acceleration, that is, centripetal acceleration, since the tangential speed is a constant.

This text is adapted from Openstax, University Physics Volume 1, Section 10.3: Relating Angular and Translational Quantities.