5.9:

Effusion und Diffusion

5.9:

Effusion und Diffusion

Although gaseous molecules travel at tremendous speeds (hundreds of meters per second), they collide with other gaseous molecules and travel in many different directions before reaching the desired target. At room temperature, a gaseous molecule will experience billions of collisions per second. The mean free path is the average distance a molecule travels between collisions. The mean free path increases with decreasing pressure; in general, the mean free path for a gaseous molecule will be hundreds of times the diameter of the molecule

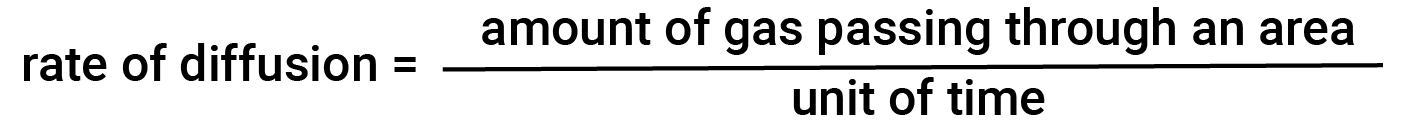

In general, when a sample of gas is introduced to one part of a closed container, its molecules very quickly disperse throughout the container; this process by which molecules disperse in space in response to differences in concentration is called diffusion. The gaseous atoms or molecules are, of course, unaware of any concentration gradient; they simply move randomly — regions of higher concentration have more particles than regions of lower concentrations, and so a net movement of species from high to low concentration areas takes place. In a closed environment, diffusion will ultimately result in equal concentrations of gas throughout. The gaseous atoms and molecules continue to move, but since their concentrations are the same in both bulbs, the rates of transfer between the bulbs are equal (no net transfer of molecules occurs). The amount of gas passing through some area per unit time is the rate of diffusion.

The diffusion rate depends on several factors: the concentration gradient (the increase or decrease in concentration from one point to another), the amount of surface area available for diffusion, and the distance the gas particles must travel.

A process involving the movement of gaseous species similar to diffusion is effusion, the escape of gas molecules through a tiny hole, such as a pinhole in a balloon into a vacuum. Although diffusion and effusion rates both depend on the molar mass of the gas involved, their rates are not equal; however, the ratios of their rates are the same.

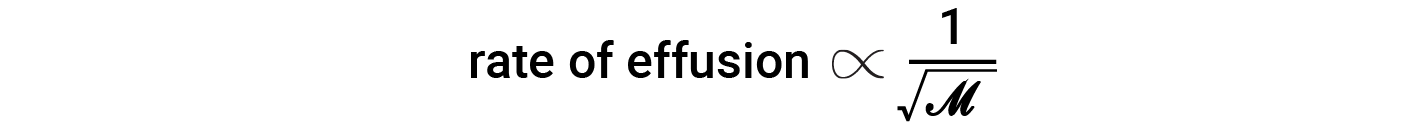

If a mixture of gases is placed in a container with porous walls, the gases effuse through the small openings in the walls. The lighter gases pass through the small openings more rapidly (at a higher rate) than the heavier one. In 1832, Thomas Graham studied the rates of effusion of different gases and formulated Graham’s law of effusion: The rate of effusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of the mass of its particles:

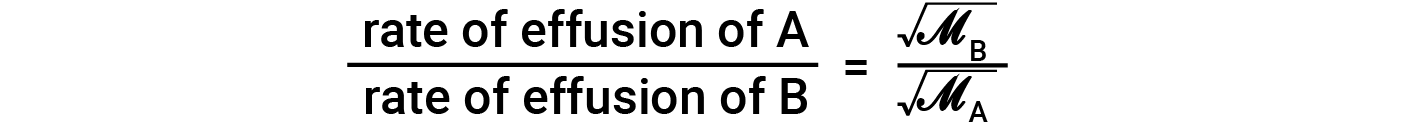

This means that if two gases, A and B, are at the same temperature and pressure, the ratio of their effusion rates is inversely proportional to the ratio of the square roots of the masses of their particles:

The relationship indicates that the lighter gas has a higher effusion rate.

For example, a helium-filled rubber balloon deflates faster than an air-filled one because the rate of effusion through the pores of the rubber is faster for the lighter helium atoms than for the air molecules.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 9.4: Effusion and Diffusion of Gases.