5.10:

Reale Gase - Abweichung von der thermischen Zustandsgleichung idealer Gase

5.10:

Reale Gase - Abweichung von der thermischen Zustandsgleichung idealer Gase

Thus far, the ideal gas law, PV = nRT, has been applied to a variety of different types of problems, ranging from reaction stoichiometry and empirical and molecular formula problems to determining the density and molar mass of a gas. However, the behavior of a gas is often non-ideal, meaning that the observed relationships between its pressure, volume, and temperature are not accurately described by the gas laws.

According to kinetic molecular theory, particles of an ideal gas do not exhibit attractive or repulsive forces on one another. They are assumed to have a negligible volume compared with that of the container. At room temperature and 1 atm or less, gases follow the ideal behavior, as implied by the ideal gas equation.

At higher pressures or lower temperatures, however, deviations from the ideal gas law occur, meaning that the observed relationships between its pressure, volume, and temperature are not accurately followed.

Rearranging the ideal gas equation to solve for n gives:

For 1 mole of an ideal gas, the ratio PV/RT = 1, regardless of pressure. Any deviation of this ratio from one is an indication of non-ideal behavior.

The ideal gas law does not describe gas behavior well at relatively high pressures. Meaning, the ratio equals 1 only at low pressures. But as the pressure rises, PV/RT begins to deviate from 1, and the deviations are not uniform. At high pressures, the deviation from ideal behavior is large and different for each gas. Real gases, in other words, do not behave ideally at high pressure. At lower pressures (usually below 10 atm), however, the deviation from ideal behavior is small, and we can use the ideal-gas equation.

Particles of a hypothetical ideal gas have no significant volume and do not attract or repel each other. In general, real gases approximate this behavior at relatively low pressures and high temperatures. However, at high pressures, the molecules of a gas are crowded closer together, and the amount of empty space between the molecules is reduced. At these higher pressures, the volume of the gas molecules themselves becomes appreciable relative to the total volume occupied by the gas. The gas, therefore, becomes less compressible at these high pressures, and although its volume continues to decrease with increasing pressure, this decrease is not proportional as predicted by Boyle’s law.

At relatively low pressures, gas molecules have practically no attraction for one another because they are (on average) so far apart, and they behave almost like particles of an ideal gas. At higher pressures, however, the force of attraction is also no longer insignificant. This force pulls the molecules a little closer together, slightly decreasing the pressure (if the volume is constant) or decreasing the volume (at constant pressure). This change is more pronounced at low temperatures because the molecules have lower KE relative to the attractive forces, and so they are less effective in overcoming these attractions after colliding with one another.

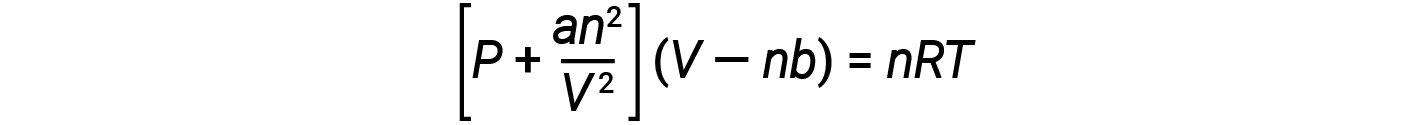

There are several different equations that better approximate gas behavior than does the ideal gas law. The first, and simplest of these, was developed by the Dutch scientist Johannes van der Waals in 1879. The van der Waals equation improves upon the ideal gas law by adding two terms: one to account for the volume of the gas molecules and another for the attractive forces between them.

The constant a corresponds to the strength of the attraction between molecules of a particular gas, and the constant b corresponds to the size of the molecules of a particular gas. The “correction” to the pressure term in the ideal gas law is an2/V2, and the “correction” to the volume is nb. Note that when V is relatively large and n is relatively small, both of these correction terms become negligible, and the van der Waals equation reduces to the ideal gas law, PV = nRT. Such a condition corresponds to a gas in which a relatively low number of molecules is occupying a relatively large volume, that is, a gas at relatively low pressure.

At low pressures, the correction for intermolecular attraction, a, is more important than the one for molecular volume, b. At high pressures and small volumes, the correction for the volume of the molecules becomes important because the molecules themselves are incompressible and constitute an appreciable fraction of the total volume. At some intermediate pressure, the two corrections have opposing influences, and the gas appears to follow the relationship given by PV = nRT over a small range of pressures.

Strictly speaking, the ideal gas equation functions well when intermolecular attractions between gas molecules are negligible, and the gas molecules themselves do not occupy an appreciable part of the whole volume. These criteria are satisfied under conditions of low pressure and high temperature. Under such conditions, the gas is said to behave ideally, and deviations from the gas laws are small enough that they may be disregarded — this is, however, very often not the case.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 9.2: Non-ideal Gas Behavior.