8.5:

Elektronenaffiniteit

8.5:

Elektronenaffiniteit

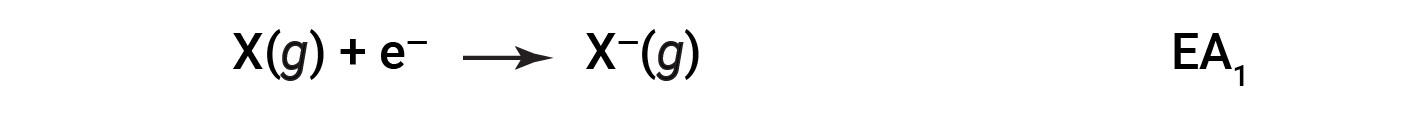

The electron affinity (EA) is the energy change for adding an electron to a gaseous atom to form an anion (negative ion).

This process can be either endothermic or exothermic, depending on the element. Many of these elements have negative values of EA, which means that energy is released when the gaseous atom accepts an electron. However, for some elements, energy is required for the atom to become negatively charged, and the value of their EA is positive. Just as with ionization energy, subsequent EA values are associated with forming ions with more charge. The second EA is the energy associated with adding an electron to an anion to form a 2– ion, and so on.

As one might predict, it becomes easier to add an electron across a series of atoms as the effective nuclear charge of the atoms increases. As we go from left to right across a period, EAs tend to become more negative. The exceptions found among the elements of group 2 (2A), group 15 (5A), and group 18 (8A) can be understood based on the electronic structure of these groups. The noble gases, group 18 (8A), have a completely filled shell, and the incoming electron must be added to a higher n level, which is more difficult to do. Group 2 (2A) has a filled ns subshell, and so the next electron added goes into the higher energy np, so, again, the observed EA value is not as the trend would predict. Finally, group 15 (5A) has a half-filled np subshell, and the next electron must be paired with an existing np electron. In all of these cases, the initial relative stability of the electron configuration disrupts the trend in EA.

One might expect the atom at the top of each group to have the most negative EA; their first ionization potentials suggest that these atoms have the largest effective nuclear charges. However, as we move down a group, we see that the second element in the group most often has the most negative EA. This can be attributed to the small size of the n = 2 shell and the resulting large electron-electron repulsions. For example, chlorine, with an EA value of –348 kJ/mol, has the highest value of any element in the periodic table. The EA of fluorine is –322 kJ/mol. When we add an electron to a fluorine atom to form a fluoride anion (F–), we add an electron to the n = 2 shell. The electron is attracted to the nucleus, but there is also significant repulsion from the other electrons already present in this small valence shell. The chlorine atom has the same electron configuration in the valence shell, but because the entering electron is going into the n = 3 shell, it occupies a considerably larger region of space and the electron-electron repulsions are reduced. The entering electron does not experience as much repulsion, and the chlorine atom accepts an additional electron more readily, resulting in a more negative EA.

This text is adapted from OpenStax Chemistry 2e, Section 6.5: Periodic Variations in Element Properties.