13.23:

Poiseuille’s Law and Reynolds Number

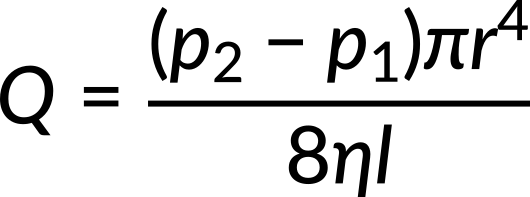

In a laminar flow, through a horizontal tube, the flow rate is defined as the ratio of pressure difference at two points and flow resistance.

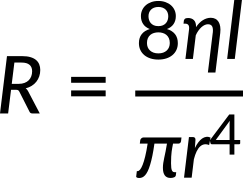

Here, resistance is directly proportional to the coefficient of viscosity and tube length, and inversely proportional to the fourth power of tube radius. When combined with the flow rate equation, this relation gives Poiseuille's law for laminar flow.

Considering the viscosity to be constant, a slight decrease in the radius of the tube causes a significant reduction in the flow rate. To maintain the same flow rate, the pressure difference has to increase accordingly.

Likewise, it is difficult for a more viscous fluid to flow through the tube than a less viscous fluid at constant temperature.

The Reynolds number is a value that indicates if the flow of a fluid is laminar or turbulent.

If the Reynolds number is below two thousand, the flow is laminar, and turbulent if it is greater than three thousand. Between two and three thousand, the flow is unstable and may show chaotic behavior.

13.23:

Poiseuille’s Law and Reynolds Number

Any fluid in a horizontal tube can flow due to pressure differences—fluid flows from high to low pressure. The flow rate (Q) is the ratio of pressure difference and resistance through a horizontal tube. The greater the pressure difference, the higher the flow rate. The flow resistance is expressed as:

When combined with the flow rate (Q), this relation gives Poiseuille's law for the laminar flow of an incompressible fluid in a tube.

All factors that affect the flow rate, except pressure, are included in resistance. Resistance depends on the dimensions of the tube and the viscosity of the fluid. Resistance is directly proportional to the length of the tube and inversely proportional to the fourth power of the radius of the tube.

In the case of a non-viscous fluid, the fluid flow is frictionless, and the resistance to flow is zero. This results in the motion of all the layers with the same velocity. In contrast, resistance to fluid flow in viscous fluids is non-zero. In such cases, the speed is greatest for the midstream and decreases towards the edge of the tube. We can see the effect in a Bunsen burner flame.

Flow can be considered to be laminar or turbulent as classified by the Reynolds number. If the Reynolds number is below 2,000, the flow is laminar; if it is greater than 3,000, the flow is turbulent. Flow is considered to be unstable and may show chaotic behavior if the Reynolds number falls between 2,000 and 3,000. Unstable flow indicates that it is initially laminar, but due to obstructions or surface roughness, the flow can become turbulent, and it may oscillate randomly between being laminar and turbulent. Here, a tiny variation in one factor can have an exaggerated (or nonlinear) effect on a system, thus showing chaotic behavior.

This text is adapted from Openstax, University Physics Volume 1, Section 14.7: Viscosity and Turbulence.