2.5:

Das Periodensystem

2.5:

Das Periodensystem

As early chemists discovered more elements, they realized that various elements could be grouped by their similar chemical behaviors. One such grouping includes lithium (Li), sodium (Na), and potassium (K). All of these elements are shiny, conduct heat and electricity well, and have similar chemical properties. A second grouping includes calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), and barium (Ba), which also are shiny, good conductors of heat and electricity, and have chemical properties in common. However, the specific properties of these two groupings are notably different from each other. For example, Li, Na, and K are much more reactive than Ca, Sr, and Ba. Additionally, Li, Na, and K form compounds with oxygen in a ratio of two of their atoms to one oxygen atom, whereas Ca, Sr, and Ba form compounds with one of their atoms to one oxygen atom. Fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), and iodine (I) also exhibit similar properties to each other, but these properties are drastically different from those of any of the elements above.

Dimitri Mendeleev in Russia (1869) and Lothar Meyer in Germany (1870) independently recognized a periodic relationship among the properties of the elements known at that time. Both published tables with the elements arranged according to increasing atomic mass. However, Mendeleev went one step further than Meyer; he used his table to predict the existence of elements that would have properties similar to aluminum and silicon but were not yet known. The discoveries of gallium (1875) and germanium (1886) provided significant support for Mendeleev’s work. Although Mendeleev and Meyer had a long dispute over priority, Mendeleev’s contributions to the development of the periodic table are now more widely recognized.

By the twentieth century, it became apparent that the periodic relationship involved atomic numbers rather than atomic masses. The modern statement of this relationship, the periodic law, states the following: the properties of the elements are periodic functions of their atomic numbers. A modern periodic table arranges the elements in increasing order of their atomic numbers, and it groups atoms with similar properties in the same vertical column. Each box represents an element and contains its atomic number, symbol, average atomic mass, and (sometimes) name.

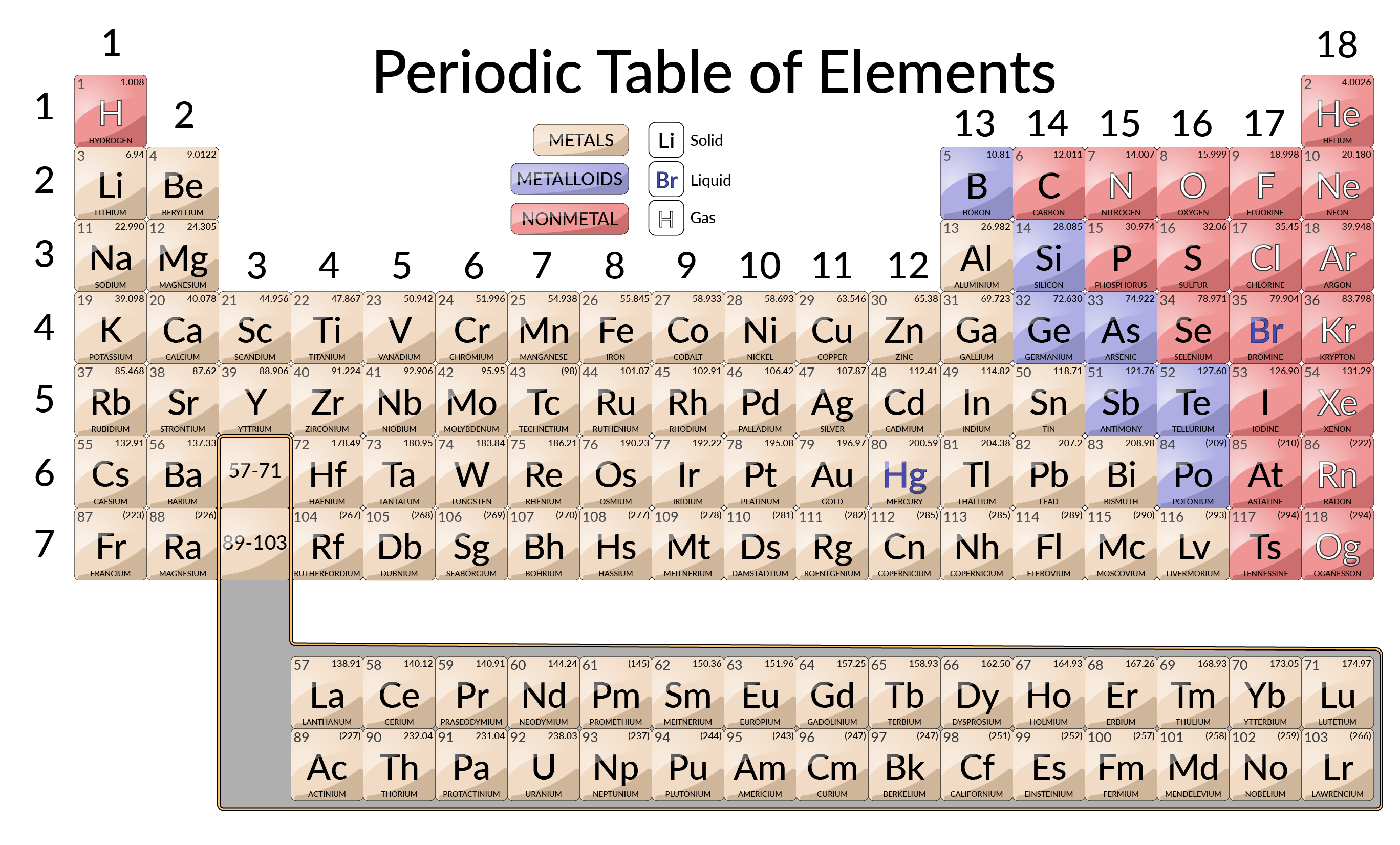

The elements are arranged in seven horizontal rows, called periods or series, and 18 vertical columns, called groups. Groups are labeled at the top of each column. For the table to fit on a single page, parts of two of the rows, a total of 14 columns, are usually written below the main body of the table.

Many elements differ significantly in their chemical and physical properties, but some elements are similar in their behaviors. For example, many elements appear shiny, are malleable and ductile, and conduct heat and electricity well. Other elements are not shiny, malleable, or ductile, and are poor conductors of heat and electricity. The elements can be sorted into large classes with common properties: metals (elements that are shiny, malleable, good conductors of heat and electricity — shaded yellow); nonmetals (elements that appear dull, poor conductors of heat and electricity — shaded red); and metalloids (elements that conduct heat and electricity moderately well, and possess some properties of metals and some properties of nonmetals — shaded purple).

The elements can also be classified into the main-group elements (or representative elements) in the columns labeled 1, 2, and 13–18; the transition metals in the columns labeled 3–12; and inner transition metals in the two rows at the bottom of the table. The top-row elements at the bottom of the table are lanthanides, and the bottom-row elements are actinides. The elements can be subdivided further by more specific properties, such as the composition of the compounds they form. For example, the elements in group 1 (the first column) form compounds that consist of one atom of the element and one atom of hydrogen. These elements (except hydrogen) are known as alkali metals, and they all have similar chemical properties. The elements in group 2 (the second column) form compounds consisting of one atom of the element and two atoms of hydrogen: These are called alkaline earth metals, with similar properties among members of that group.

Other groups with specific names are the pnictogens (group 15), chalcogens (group 16), halogens (group 17), and the noble gases (group 18, also known as inert gases). The groups can also be referred to by the first element of the group: For example, the chalcogens can be called the oxygen group or oxygen family. Hydrogen is a unique, nonmetallic element with properties similar to both group 1 and group 17 elements. For that reason, hydrogen may be shown at the top of both groups, or by itself.

Element 43 (technetium), element 61 (promethium), and most of the elements with atomic number 84 (polonium) and higher have their atomic mass given in square brackets. This is done for elements that consist entirely of unstable, radioactive isotopes (radioactivity is covered in more detail in the nuclear chemistry chapter). An average atomic weight cannot be determined for these elements because their radioisotopes may vary significantly in relative abundance, depending on the source, or may not even exist in nature. The number in square brackets is the atomic mass number, which is an approximate atomic mass of the most stable isotope of that element.

Text adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 2.5: The Periodic Table.