7.11:

Atomic Orbitals

The densest region of the electron cloud — where an electron is most likely to be found — is described in terms of atomic orbitals.

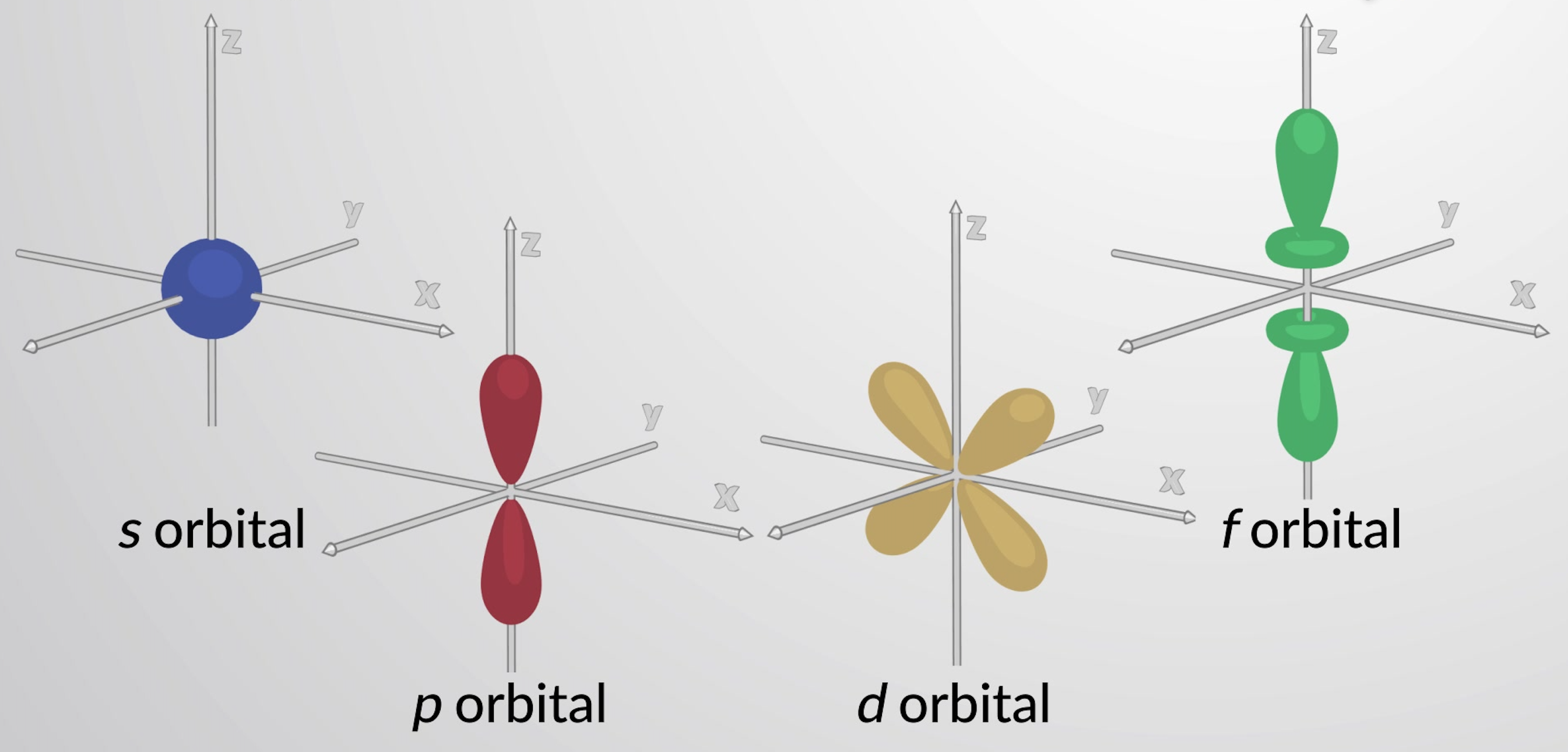

The shape of an atomic orbital is determined by the angular momentum quantum number, l. Recall that the values of l are based on the principal quantum number, n — possible values of l range from 0 to n − 1. When n is greater than one, multiple sublevels exist. Each value of l corresponds to either an s, p, d, or f orbital.

The lowest energy orbital is the 1s orbital. This is a spherically symmetric orbital. The probability density of a 1s orbital reveals that the electron is most likely to be found at the nucleus. However, given the electrostatic forces between protons and electrons — this isn’t likely.

Multiplying the probability density by the volume of thin spherical shells with radii r is more representative. The total probability of finding an electron within the thin shell at a distance r from the nucleus is the radial distribution function.

For hydrogen, the greatest probability of finding an electron is at 52.9 picometers from the nucleus. Thus, the shape of the 1s atomic orbital for hydrogen is spherical with a radius of 52.9 picometers.

The 2s and 3s orbitals are also spherical. They are larger and have nodes. At a node, the probability of finding an electron is zero.

Principal levels with n equal to two or more also contain three p-orbitals. These are lobe-shaped with a node at the nucleus. Their orientation is described by the value of ml. The three p-orbitals are orthogonal to each other.

Principal levels of n equal to three or more also have five d orbitals. The d orbitals with the cloverleaf shape have four electron-dense lobes and two perpendicular nodal planes. One of the d-orbitals is slightly different.

The f orbitals have more lobes and nodes. These orbitals exist for principal levels of n equal to four or more.

When you overlay the orbitals on top of one another, a roughly spherical shape emerges. This is why atoms are generally represented as spheres.

7.11:

Atomic Orbitals

An atomic orbital represents the three-dimensional regions in an atom where an electron has the highest probability to reside. The radial distribution function indicates the total probability of finding an electron within the thin shell at a distance r from the nucleus. The atomic orbitals have distinct shapes which are determined by l, the angular momentum quantum number. The orbitals are often drawn with a boundary surface, enclosing densest regions of the cloud.

The angular momentum quantum number is an integer that may take the values, l = 0, 1, 2, …, n – 1. An orbital with a principal quantum number of 1 (n = 1) can have only one value of l (l = 0), whereas a principal quantum number of 2 (n = 2) permits l = 0 and l = 1. Orbitals with the same value of l define a subshell.

Orbitals with l = 0 are called s orbitals and they make up the s subshells. The value l = 1 corresponds to the p orbitals. For a given n, p orbitals constitute a p subshell (i.e., 3p if n = 3). The orbitals with l = 2 are called the d orbitals. The orbitals with l = 3, 4, and 5 are the f, g, and h orbitals.

The lowest energy orbital is the 1s orbital. This is a spherically symmetric orbital. The probability density (ψ2) of a 1s orbital implies that the electron is most likely to be found at the nucleus. However, given the electrostatic forces between protons and electrons, this does not accurately represent where the electron will reside. Instead, the Radial Distribution Function is used, which is a plot of the total probability of finding an electron in an orbital at a given radius r. The radial distribution function is found by multiplying the probability density by the volume of thin spherical shells with radii, r. For the 1s orbital of hydrogen, the Radial Distribution Function has a value zero at the nucleus, which increases to a maximum at 52.9 picometers before decreasing with increasing r.

There are certain distances from the nucleus at which the probability density of finding an electron located at a particular orbital is zero. In other words, the value of the wavefunction ψ is zero at this distance for this orbital. Such a value of r is called a radial node. The number of radial nodes in an orbital is n – l – 1. For 2s orbitals, where n = 1, there is one radial node, whereas 3s orbitals have two radial nodes.

Each principal level with n = 2 or more contains three p orbitals. The three p orbitals have two lobes with a node located at the nucleus . The orientation of p orbitals in space is described by the value of ml. The three p orbitals are mutually perpendicular (orthogonal) to each other. The higher p orbitals (3p, 4p, 5p, and higher) have similar shapes but are larger in size with additional radial nodes.

Principal levels with n = 3 or more contain five d orbitals. Four of these orbitals consist of a cloverleaf shape, with four electron-dense lobes. There are two perpendicular nodal planes that intersect at the nucleus. At these nodal planes, the electron density is zero. One of the d orbitals is slightly different in shape and has two lobes oriented in the z-axis with a donut-shaped ring in the xy plane. Principal levels with n = 4 and greater contain seven f orbitals, which have complex shapes. These orbitals have more nodes and lobes than d orbitals.

Figure 1: Representative s, p, d, and f orbitals.

These different shapes of the atomic orbitals represent the three-dimensional regions within which the electron is likely to be found. All the orbitals together make up a roughly spherical shape, which is why atoms are generally represented as spheres.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 6.3: Development of Quantum Theory.