12.13:

Colloids

When salt is added to water, it dissolves to form a solution. Conversely, when sand is added to water and stirred, the sand particles are spread throughout the liquid to form a suspension, and finally settle at the bottom.

However, when flour is added to water, the water becomes cloudy. This is because flour and water form a colloidal dispersion or a colloid.

A colloid is a mixture in which particles of a solute-like substance are finely dispersed in a solvent-like medium.

The dispersed particles and the dispersing medium can be any combination of solid and liquid, such as opal, liquid and liquid, such as milk, liquid and gas, such as whipped cream, except that they cannot both be gases.

Properties of a colloid are intermediate between those of suspensions and solutions.

Colloids are heterogeneous mixtures like suspensions, in contrast to solutions, which are homogeneous.

With a size of 5 to 1000 nanometers, colloidal particles are much larger than the usual solute molecules, which are around 1 nanometer or less, and smaller than suspended particles, which are 10,000 nanometers or larger.

A laser beam passing through a solution is invisible but can be easily seen in a colloidal dispersion. This is because the colloid particles are large enough to scatter the light while solute particles are too small to do so.

This scattering of light by colloidal particles is called the Tyndall effect.

Colloidal particles can remain stably dispersed throughout the medium by colliding with other molecules and moving constantly in a random path. This movement is called Brownian motion.

If a suspension, a solution, and a colloid are centrifuged, only the suspension separates.

Water-based colloids can be hydrophilic, water-loving, or hydrophobic, water-fearing.

For example, when agar, a seaweed extract, is added to hot water, it forms a hydrophilic colloid.

Hydrophobic colloids, such as oil and vinegar, are unstable in water and tend to separate.

Such colloidal dispersions can be stabilized by adding other substances that attach to the surfaces of the colloidal particles. These additives can be ions that repel other ions on neighboring colloidal particles to remain dispersed.

Other additives can cover the colloid particle surface with hydrophilic groups. For example, sodium stearate, a type of soap, has a sodium ion along with a polar head and a long nonpolar tail of fatty acid.

In water, the soap molecules aggregate in spheres so that their hydrophobic tails point inwards while their charged hydrophilic heads are outside. These spherical structures are called micelles.

The hydrophobic tails trap the non-polar oil inside the micelles while the hydrophilic outside interacts with water. This explains the phenomena seen when soap is washed with water and oil is removed.

12.13:

Colloids

Children at play often make suspensions such as mixtures of mud and water, flour and water, or a suspension of solid pigments in water known as tempera paint. These suspensions are heterogeneous mixtures composed of relatively large particles that are visible to the naked eye or can be seen with a magnifying glass. They are cloudy, and the suspended particles settle out after mixing. On the other hand, a solution is a homogeneous mixture in which no settling occurs and in which the dissolved species are molecules or ions. Solutions exhibit completely different behavior from suspensions. A solution may be colored, but it is transparent, the molecules or ions are invisible, and they do not settle out on standing. Another class of mixtures called colloids (or colloidal dispersions) exhibit properties intermediate between those of suspensions and solutions. The particles in a colloid are larger than most simple molecules; however, colloidal particles are small enough that they do not settle out upon standing.

Preparation of Colloidal Systems

Colloids are prepared by producing particles of colloidal dimensions and distributing these particles throughout a dispersion medium. Particles of colloidal size are formed by two methods:

• Dispersion methods: breaking down larger particles. For example, paint pigments are produced by dispersing large particles by grinding in special mills.

• Condensation methods: growth from smaller units, such as molecules or ions. For example, clouds form when water molecules condense and form very small droplets.

A few solid substances, when brought into contact with water, disperse spontaneously and form colloidal systems. Gelatin, glue, starch, and dehydrated milk powder behave in this manner. The particles are already of colloidal size; the water simply disperses them. Powdered milk particles of colloidal size are produced by dehydrating milk spray. Some atomizers produce colloidal dispersions of a liquid in air.

An emulsion may be prepared by shaking together or blending two immiscible liquids. This breaks one liquid into droplets of colloidal size, which then disperse throughout the other liquid. Oil spills in the ocean may be difficult to clean up, partly because wave action can cause the oil and water to form an emulsion. In many emulsions, however, the dispersed phase tends to coalesce, form large drops, and separate. Therefore, emulsions are usually stabilized by an emulsifying agent, a substance that inhibits the coalescence of the dispersed liquid. For example, a little soap will stabilize an emulsion of kerosene in water. Milk is an emulsion of butterfat in water, with the protein casein serving as the emulsifying agent. Mayonnaise is an emulsion of oil in vinegar, with egg yolk components as the emulsifying agents.

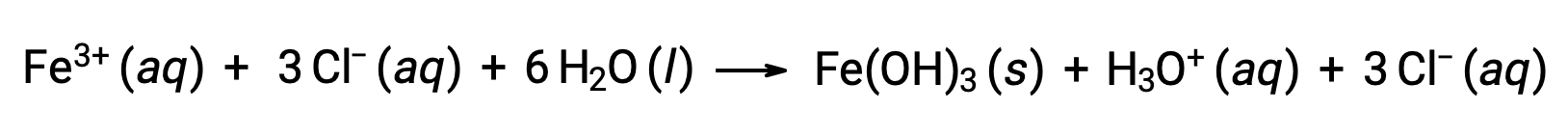

Condensation methods form colloidal particles by aggregation of molecules or ions. If the particles grow beyond the colloidal size range, drops or precipitates form, and no colloidal system results. Clouds form when water molecules aggregate and form colloid-sized particles. If these water particles coalesce to form adequately large water drops of liquid water or crystals of solid water, they settle from the sky as rain, sleet, or snow. Many condensation methods involve chemical reactions. A red colloidal suspension of iron(III) hydroxide may be prepared by mixing a concentrated solution of iron(III) chloride with hot water:

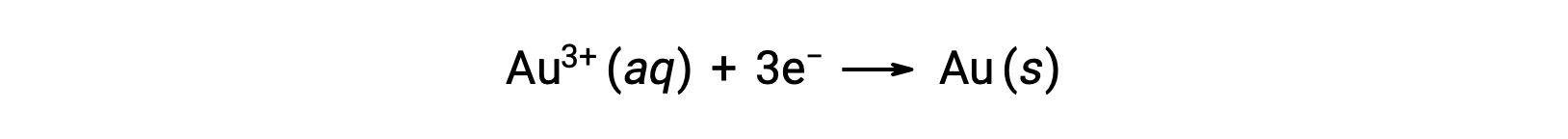

A colloidal gold sol results from the reduction of a very dilute solution of gold(III) chloride by a reducing agent such as formaldehyde, tin(II) chloride, or iron(II) sulfate:

Some gold sols prepared in 1857 are still intact (the particles have not coalesced and settled), illustrating the long-term stability of many colloids.

Soaps and Detergents

Pioneers made soap by boiling fats with a strongly basic solution made by leaching potassium carbonate, K2CO3, from wood ashes with hot water. Animal fats contain polyesters of fatty acids (long-chain carboxylic acids). When animal fats are treated with a base like potassium carbonate or sodium hydroxide, glycerol and salts of fatty acids such as palmitic, oleic, and stearic acid are formed. The salts of fatty acids are called soaps. The sodium salt of stearic acid, sodium stearate, contains an uncharged nonpolar hydrocarbon chain, the C17H35 unit, and an ionic carboxylate group, the COO− unit.

The cleaning action of soaps and detergents can be explained in terms of the structures of the molecules involved. The hydrocarbon (nonpolar) end of a soap or detergent molecule dissolves in or is attracted to nonpolar substances, such as oil, grease, or dirt particles. The ionic end is attracted by water (polar). As a result, the soap or detergent molecules become oriented at the interface between the dirt particles and the water, so they act as a kind of bridge between two different kinds of matter, nonpolar and polar. Molecules such as this are termed amphiphilic since they have both a hydrophobic (“water-fearing”) part and a hydrophilic (“water-loving”) part. As a consequence, dirt particles become suspended as colloidal particles and are readily washed away.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 11.5: Colloids.

Suggested Reading

- Riley, John T. "Appetizing colloids." Journal of Chemical Education 57, no. 2 (1980): 153.

- Friberg, Stig E., and Beverly Bendiksen. "A simple experiment illustrating the structure of association colloids." Journal of Chemical Education 56, no. 8 (1979): 553.

- Liang, Fuxin, Bing Liu, Zheng Cao, and Zhenzhong Yang. "Janus colloids toward interfacial engineering." Langmuir 34, no. 14 (2017): 4123-4131.

- Hansen, Robert S., and C. A. Smolders. "Colloid and surface chemistry in the mainstream of modern chemistry." (1962): 167.