9.5:

Radioactive Decay and Radiometric Dating

9.5:

Radioactive Decay and Radiometric Dating

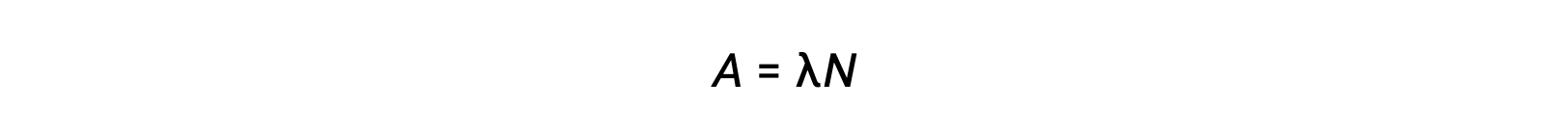

Radioactivity is a spontaneous disintegration of an unstable nuclide and is a random process, as all the nuclei in the sample do not decay simultaneously. The number of disintegrations per unit time is called the activity (A), which is directly proportional to the number of nuclei in the sample. The decay constant (λ) is an average probability of decay per nucleus in unit time.

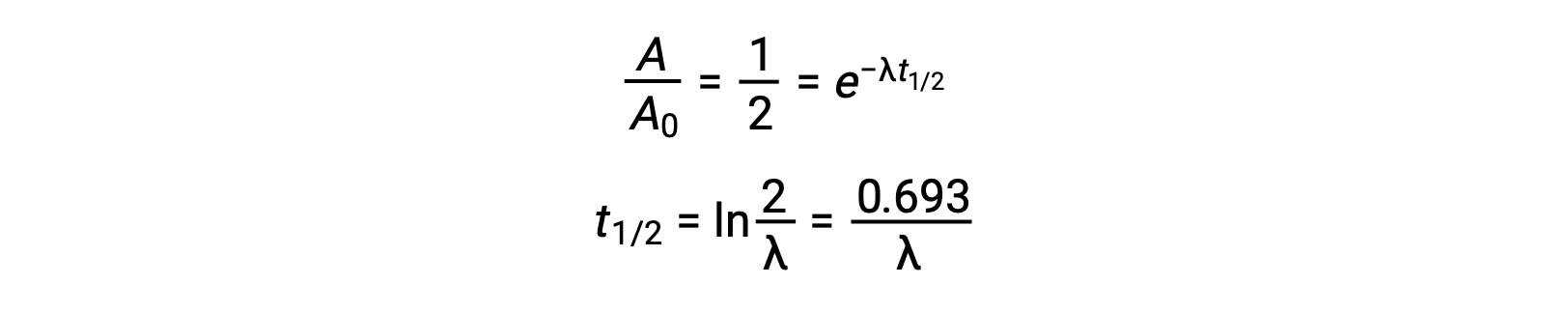

The SI unit for activity is the becquerel, which is one disintegration per second. Another unit of activity is the curie, which is equal to 37 billion becquerels. Plotting activity vs time for different radionuclides indicates different decay rates. The time required for the activity to fall from any value to half of that value is one half-life, indicated as t1/2.

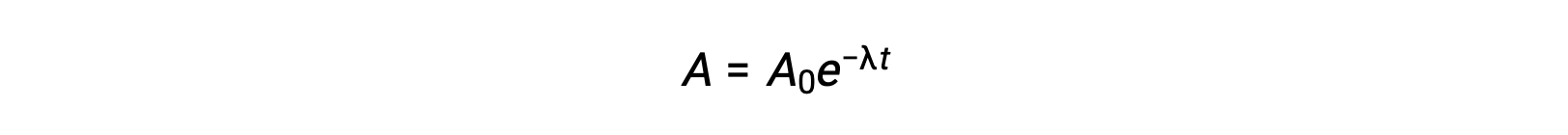

As the activity is proportional to the number of radioactive atoms, it decreases with time as the amount of sample diminishes. Mathematically, the activity of a radionuclide is indicated by an exponential equation:

Thus, when activity is reduced to half, rearranging the equation provides a way to calculate the half-life, which is inversely proportional to the decay constant.

A half-life is an intrinsic property of a radionuclide, and any single atom of an unstable nuclide has the same half-life regardless of whether it is completely alone in a vacuum or in a sample with many other atoms of that nuclide. The half-lives of radionuclides vary widely: radon-220 has a half-life of 1 minute: one million nuclei decay down to half a million in a minute and further decay to one fourth of a million in another minute. However, thorium-232 has a half-life of 14 billion years.

Several radioisotopes have half-lives and other properties that make them useful for purposes of “dating” the temporal origin of objects such as archaeological artifacts, formerly living organisms, or geological formations.

Carbon-14, a radionuclide with a half-life of 5730 years, provides a method for dating objects that were a part of a living organism. This method of radiometric dating is accurate for dating carbon-containing substances that are up to about 30,000 years old and can provide reasonably accurate dates up to a maximum of about 50,000 years old.

Naturally occurring carbon consists of three isotopes: carbon-12, which constitutes about 99% of the carbon on earth; carbon-13, about 1% of the total; and trace amounts of carbon-14. Carbon-14 forms in the upper atmosphere by the reaction of nitrogen atoms with neutrons from cosmic rays in space.

All isotopes of carbon react with oxygen to produce CO2 molecules. Thus, living plants and animals have a ratio of carbon-14 and carbon-12 identical to the atmosphere. But when the living plant or animal dies, replenishment of carbon stops, and the carbon-14 to 12 ratio starts diminishing as the radioactive carbon-14 continuously decays. For example, if the carbon-14 to carbon-12 ratio in a wooden object found in an archaeological dig is half what it is in a living tree, this suggests that the object was made from wood cut down 5730 years ago. Highly accurate determinations of carbon-14 to carbon-12 ratios can be obtained from very small samples (as little as a milligram) using a mass spectrometer.

Radioactive dating can also use other radioactive nuclides with longer half-lives to date older events. For example, uranium-238, which decays in a series of steps into lead-206, can be used for establishing the age of rocks (and the approximate age of the oldest rocks on earth). Since uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.5 billion years, it takes that amount of time for half of the original uranium-238 to decay into lead-206. In a sample of rock that does not contain appreciable amounts of lead-208, the most abundant isotope of lead, we can assume that lead was not present when the rock was formed. Therefore, by measuring and analyzing the ratio of U-238:Pb-206, we can determine the age of the rock. This assumes that all of the lead-206 present came from the decay of uranium-238. If there is additional lead-206 present, which is indicated by the presence of other lead isotopes in the sample, it is necessary to make an adjustment. Potassium–argon dating uses a similar method. Potassium-40 decays by positron emission and electron capture to form argon-40 with a half-life of 1.25 billion years. If a rock sample is crushed and the amount of argon-40 gas that escapes is measured, determination of the Ar-40:K-40 ratio yields the age of the rock.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 21.3: Radioactive Decay.