9.6:

Covalent Bonding and Lewis Structures

Covalent bonds are formed between nonmetals by the sharing of valence electrons. But why do nonmetals prefer to share electrons rather than transfer them like in ionic bonds? Nonmetals have high ionization energies, which makes it difficult to transfer valence electrons from one atom to another.

Consider a molecule of ammonia. The nitrogen atom requires three more electrons to reach an octet, and the hydrogen atom needs an electron to reach a duet.

Therefore, the nitrogen atom bonds with three hydrogen atoms such that both nitrogen and hydrogen reach stable electron configurations. Since each of these bonds shares one pair of electrons, it is called a single bond.

The shared pair of electrons in the covalent bond is called a bonding pair. The valence electrons not participating in bonding are called the lone pair or nonbonding electrons.

With 6 valence electrons, oxygen atoms need two more electrons to reach an octet. Therefore, two oxygen atoms share two-electron pairs forming a double bond. Nitrogen, on the other hand, shares the three unpaired electrons in its diatomic form, creating a triple bond.

Single and multiple bonds differ in terms of bond length and strength. Triple bonds are shorter than double bonds, which are shorter than single bonds. The bond strength increases with bond multiplicity. This is why it is hard to break the triple bond in nitrogen, making it relatively unreactive.

The Lewis model helps to predict the structure and stability of molecules. According to the Lewis model, H2O is a stable molecule; because both oxygen and hydrogen have achieved stable electron configurations.

If the oxygen shares electrons with only one hydrogen atom, the resulting OH molecule is not stable since oxygen has only 7 valence electrons and cannot reach the octet. However, if an extra electron is added to the oxygen to complete the octet, the resulting hydroxide ion becomes stable with a negative charge.

Covalent bonds are directional because the shared electrons link two specific pairs of atoms. In contrast, ionic bonds are nondirectional and hold several ions in the lattice. Thus, in a covalent compound, the individual molecules are considered to be fundamental units.

9.6:

Covalent Bonding and Lewis Structures

Compared to ionic bonds, which results from the transfer of electrons between metallic and nonmetallic atoms, covalent bonds result from the mutual attraction of atoms for a “shared” pair of electrons.

Covalent bonds are formed between two atoms when both have similar tendencies to attract electrons to themselves (i.e., when both atoms have identical or fairly similar ionization energies and electron affinities).

Physical Properties of Covalent Compounds

Compounds that contain covalent bonds exhibit different physical properties than ionic compounds. Because the attraction between molecules, which are electrically neutral, is weaker than that between electrically charged ions, covalent compounds generally have much lower melting and boiling points than ionic compounds. In fact, many covalent compounds are liquids or gases at room temperature, and, in their solid states, they are typically much softer than ionic solids. Furthermore, whereas ionic compounds are good conductors of electricity when dissolved in water, most covalent compounds are insoluble in water; since they are electrically neutral, they are poor conductors of electricity in any state.

Formation of Covalent Bonds

Nonmetal atoms frequently form covalent bonds with other nonmetal atoms. For example, the hydrogen molecule, H2, contains a covalent bond between its two hydrogen atoms. Two separate hydrogen atoms with particular potential energy approach each other, their valence orbitals (1s) begin to overlap. The single electrons on each hydrogen atom then interact with both atomic nuclei, occupying the space around both atoms. The strong attraction of each shared electron to both nuclei stabilizes the system, and the potential energy decreases as the bond distance decreases. If the atoms continue to approach each other, the positive charges in the two nuclei begin to repel each other, and the potential energy increases. The bond length is determined by the distance at which the lowest potential energy is achieved.

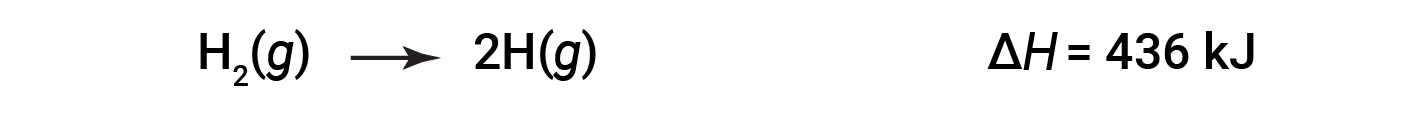

It is essential to remember that energy must be added to break chemical bonds (an endothermic process), whereas forming chemical bonds releases energy (an exothermic process). In the case of H2, the covalent bond is very strong; a large amount of energy, 436 kJ, must be added to break the bonds in one mole of hydrogen molecules and cause the atoms to separate:

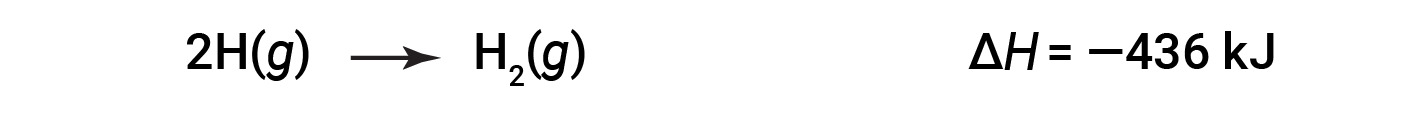

Conversely, the same amount of energy is released when one mole of H2 molecules forms from two moles of H atoms:

Lewis Structures

Lewis symbols can be used to indicate the formation of covalent bonds, which are shown in Lewis structures, drawings that describe the bonding in molecules and polyatomic ions. For example, when two chlorine atoms form a chlorine molecule, they share one pair of electrons:

The Lewis structure indicates that each Cl atom has three pairs of electrons that are not used in bonding (called lone pairs) and one shared pair of electrons (written between the atoms). A dash (or line) is sometimes used to indicate a shared pair of electrons: Cl—Cl.

- A single shared pair of electrons is called a single bond. Each Cl atom interacts with eight valence electrons: the six in the lone pairs and the two in the single bond.

- However, a pair of atoms may need to share more than one pair of electrons in order to achieve the requisite octet. A double bond forms when two pairs of electrons are shared between a pair of atoms, as between the carbon and oxygen atoms in CH2O (formaldehyde) and between the two carbon atoms in C2H4 (ethylene).

- A triple bond forms when three electron pairs are shared by a pair of atoms, as in carbon monoxide (CO) and the cyanide ion (CN–).

The periodic table can be used to predict the number of valence electrons in an atom and the number of bonds that will be formed to reach an octet. Group 18 elements such as Argon and Helium have filled electron configuration and thus rarely participate in chemical bonding. However, atoms from group 17, such as bromine or iodine, need only one electron to reach octet. Hence atoms belonging to group 17 can form a single covalent bond. The atoms of group 16 need 2 electrons to reach an octet; hence they can form two covalent bonds. Similarly, carbon that belongs to group 14, needs 4 more electrons to reach an octet; thus carbon can form four covalent bonds.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 7.2: Covalent Bonds and Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 7.3: Lewis Symbols and Structures.