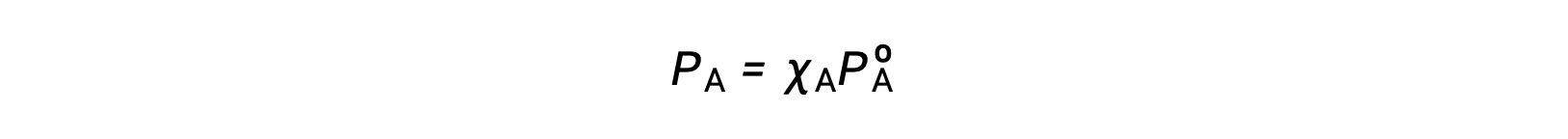

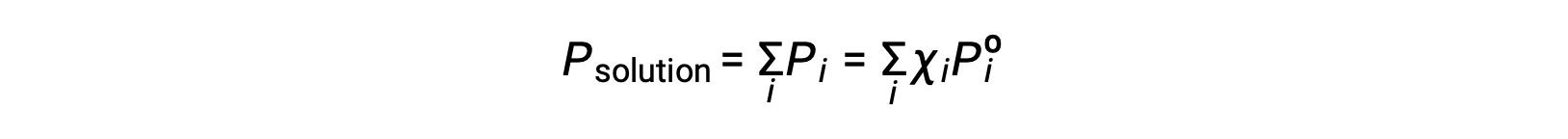

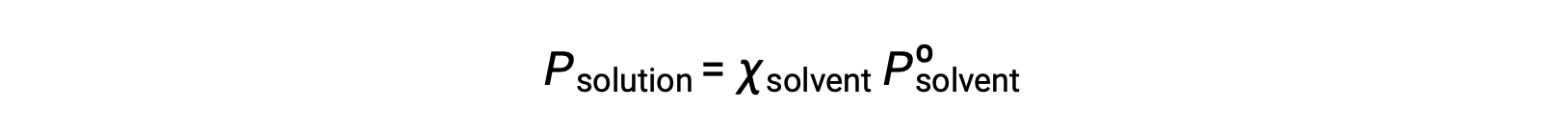

Some properties of a solution depend on the type of solute. An aqueous solution of hydrochloric acid turns a pH paper red, while a sodium hydroxide solution turns it blue. Other properties of a solution depend only on the concentration or the number of particles of the solute rather than the type of solute. These are called colligative properties. One such property is the vapor pressure of a solution. The vapor pressure of a liquid is the pressure of the gas above the liquid resulting from evaporation when the liquid and the gas are in a dynamic equilibrium in a closed container. The vapor pressure of the solution is always less than that of the pure solvent. Consider a solution made when a non-volatile solute, that is one with no measurable vapor pressure, is added to a volatile solvent. In a pure solvent, the entire surface of the liquid is solvent particles. Some of these particles escape into the gaseous state to create vapor, while some of the gas molecules above condense back into a liquid state. When the rate of vaporization equals the rate of condensation, a dynamic equilibrium is reached. In a solution, the liquid surface has both solute and solvent particles. So, a smaller number of the surface solvent particles can vaporize. The rate of condensation decreases to re-establish the dynamic equilibrium with the diminished rate of vaporization, now with a lower concentration of solvent particles in the gaseous state. The vapor pressure of a solution can be calculated by Raoult’s law, which states that the partial pressure of a solution is equal to the mole fraction of the solvent, X, multiplied by the vapor pressure of the pure solvent, Pº. For example, a solution contains 1.5 mol of a non-volatile solute such as glycerol and 3.5 mol of water at 25 °C. The mole fraction of the solvent is 0.70 and the vapor pressure of pure water is 23.8 torr. The vapor pressure of the solution can be calculated using Raoult’s law to be 16.7 torr, 70% of the vapor pressure of the pure solvent. An equation for vapor pressure lowering, ΔP, can also be derived from Raoult’s Law. Since the mole fraction of the solvent is equal to one minus the mole fraction of the solute, it can be substituted into Raoult’s Law. This can be used to create an equation where vapor pressure lowering is directly proportional to the mole fraction of the solute. Recalling the previous example, the mole fraction of the solute is 1 minus the mole fraction of the solvent. Plugging in the value, the mole fraction of the solute is 0.3. Given that the vapor pressure of pure water is 23.8 torr, the lowering of vapor pressure is calculated to be 7.14 torr. Adding ΔP and the vapor pressure of the solution, the vapor pressure of the pure solvent is obtained