14.2:

The Equilibrium Constant

14.2:

The Equilibrium Constant

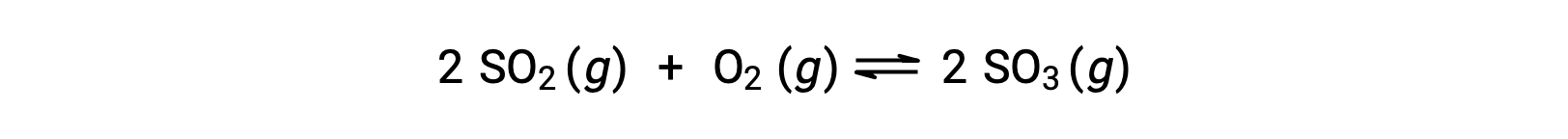

Consider the oxidation of sulfur dioxide:

For a reaction that begins with a mixture of reactants only, the product concentration is initially equal to zero. As the reaction proceeds toward equilibrium in the forward direction, the reactant concentrations decrease and the product concentration increases. When equilibrium is achieved, the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant.

If the reaction begins with only the products present, the reaction proceeds toward equilibrium in the reverse direction. The product concentration decreases with time and the reactant concentrations increase until the concentrations become constant at equilibrium.

The law of mass action states that the ratio of the concentration of products to the concentration of reactants at equilibrium, raised to their respective stoichiometric coefficients, is equal to a constant, called the equilibrium constant, K or Kc.

Thus, the equilibrium constant expression for the above reaction is written as:

where, the subscript ‘c’ indicates that the equilibrium constant considers the molar concentration of reactants and products.

The magnitude of equilibrium constant explicitly reflects the composition of a reaction mixture at equilibrium. A reaction exhibiting a large K will reach equilibrium when most of the reactant has been converted to product, whereas a small K indicates the reaction achieves equilibrium after very little reactant has been converted. It’s important to keep in mind that the magnitude of K does not indicate how rapidly or slowly equilibrium will be reached. Some equilibria are established so quickly as to be nearly instantaneous, and others so slowly that no perceptible change is observed over the course of days, years, or longer. The equilibrium constant for a reaction can be used to predict the behavior of mixtures containing its reactants and/or products. As demonstrated by the sulfur dioxide oxidation process described above, a chemical reaction will proceed in whatever direction is necessary to achieve equilibrium.

Coupled Equilibria

Many equilibrium systems involve two or more coupled equilibrium reactions, those which have in common one or more reactant or product species. The K value for a system involving coupled equilibria can be related to the K values of the individual reactions. Three basic manipulations are involved in this approach, as described below:

• Changing the direction of a chemical equation essentially swaps the identities of “reactants” and “products,” and so the equilibrium constant for the reversed equation is simply the reciprocal of that for the forward equation.

• Changing the stoichiometric coefficients in an equation by some factor x results in an exponential change in the equilibrium constant by that same factor.

• Adding two or more equilibrium equations together yields an overall equation whose equilibrium constant is the mathematical product of the individual reaction’s K values.

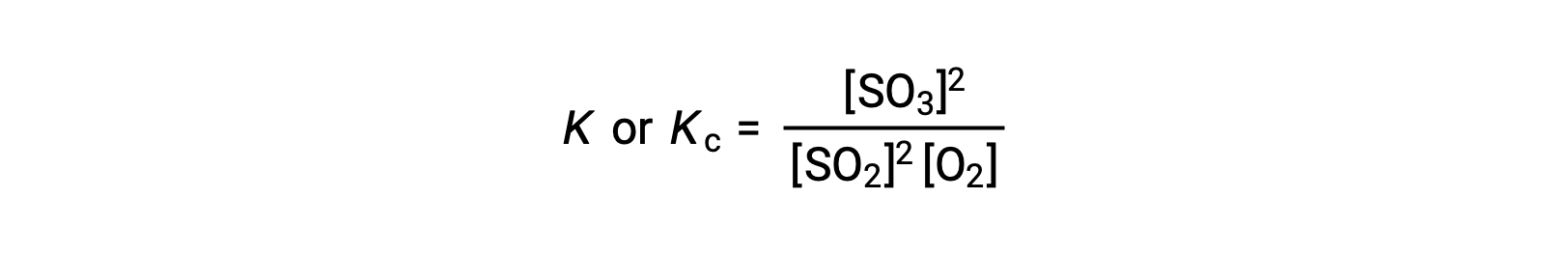

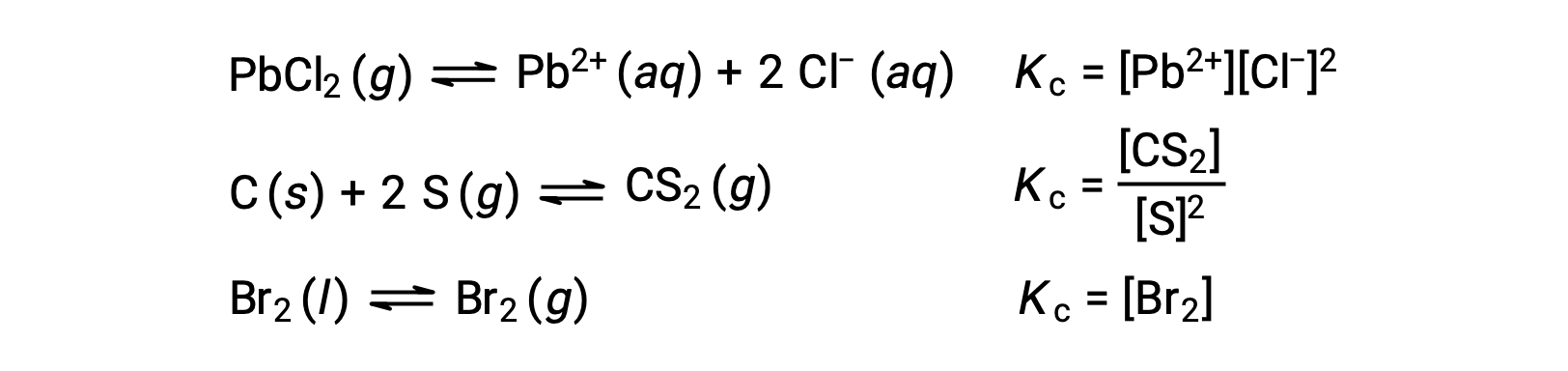

Equilibrium Constant expression for heterogeneous equilibria

For heterogeneous equilibria, involving reactants and products in two or more different phases, the concentrations of pure solids or pure liquids are not included in the equilibrium constant expression, as illustrated by the following example:

This is because the relative concentrations for pure liquids and pure solids remain constant during the reaction.

This text has been adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 13.2 Equilibrium Constants.