20.10:

Colors and Magnetism

20.10:

Colors and Magnetism

Color in Coordination Complexes

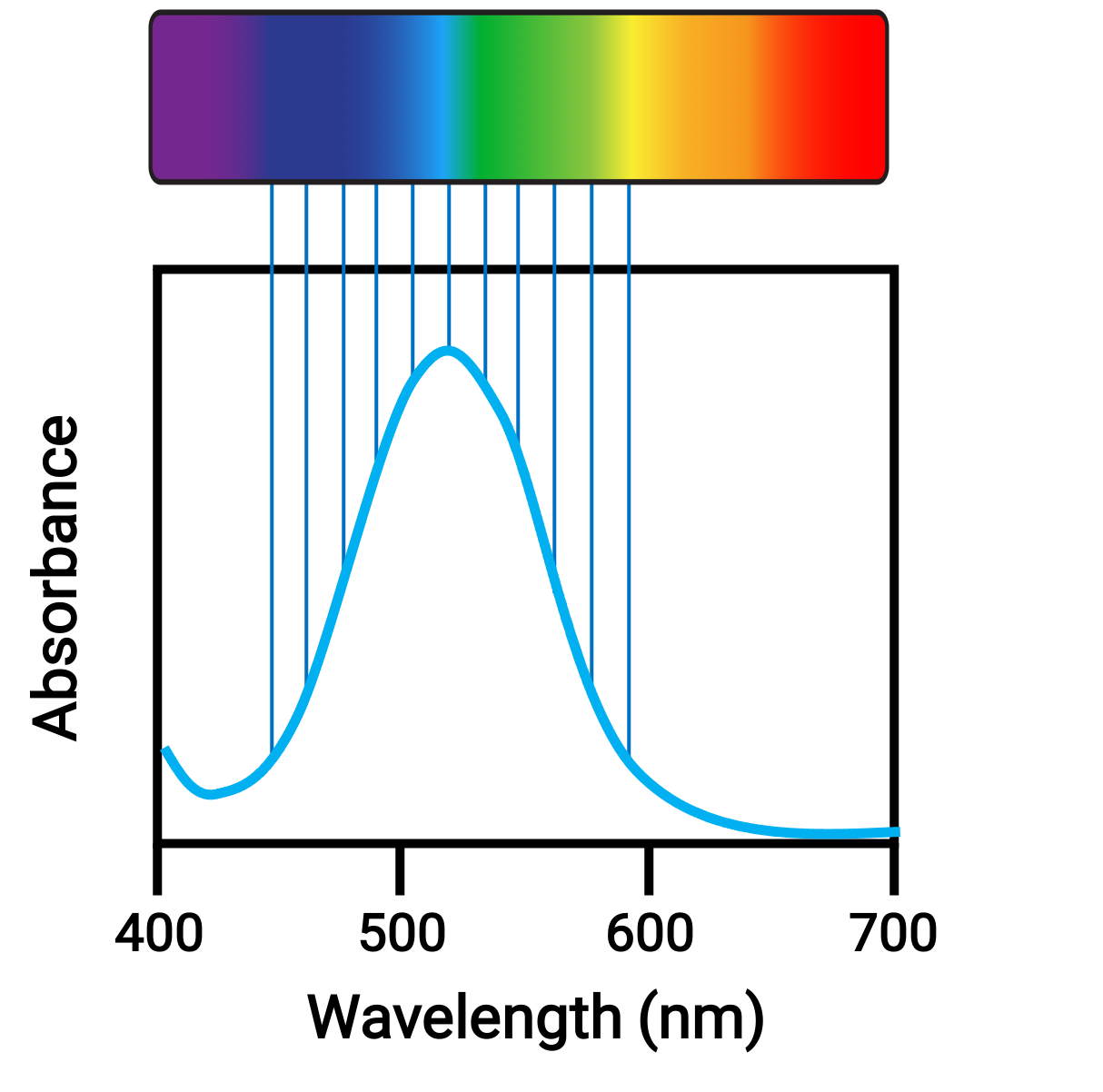

When atoms or molecules absorb light at the proper frequency, their electrons are excited to higher-energy orbitals. For many main group atoms and molecules, the absorbed photons are in the ultraviolet range of the electromagnetic spectrum, which cannot be detected by the human eye. For coordination compounds, the energy difference between the d orbitals often allows photons in the visible range to be absorbed and emitted, which is seen as colors by the human eye.

Figure 1. Electromagnetic spectrum of visible light and absorbance.

Small changes in the relative energies of the orbitals that electrons are transitioning between can lead to drastic shifts in the color of light absorbed. Therefore, the colors of the coordination compounds depend on many factors, like:

• Different aqueous metal ions can have different colors.

• Different oxidation states of one metal can produce different colors.

• Specific ligands coordinated to the metal center influence the color of coordination complexes. For example, the iron(II) complex [Fe(H2O)6]SO4 appears blue-green because the high-spin complex absorbs photons in the red wavelengths. In contrast, the low-spin iron(II) complex K4[Fe(CN)6] appears pale yellow because it absorbs higher-energy violet photons.

In general, strong-field ligands cause a large split in the energies of d orbitals of the central metal atom (large Δ). Transition metal coordination compounds with these ligands are yellow, orange, or red because they absorb higher-energy violet or blue light.

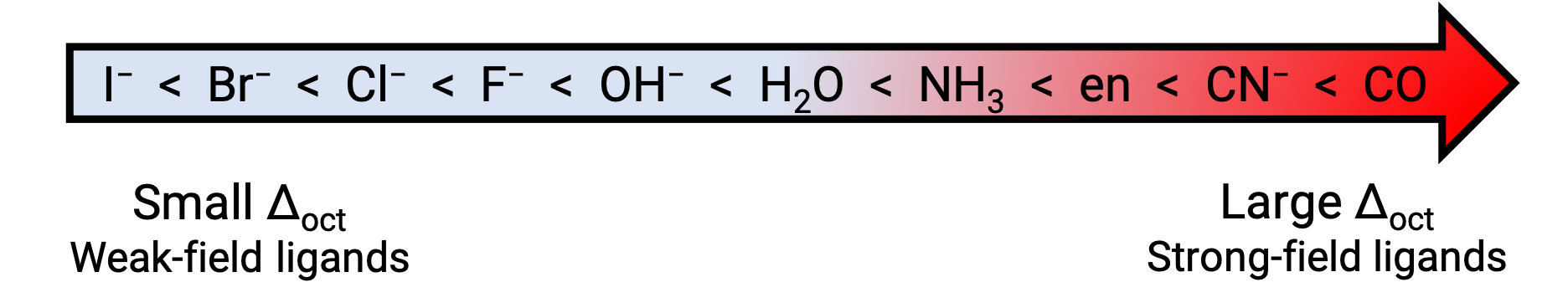

On the other hand, coordination compounds of transition metals with weak-field ligands are often blue-green, blue, or indigo because they absorb lower-energy yellow, orange, or red light. The strength of the ligands to split the d orbitals are listed in the spectrochemical series. Here the ligands are written in the increasing value of crystal field splitting energy (Δ).

Figure 2. Spectrochemical series.

For example, a coordination compound of the Cu+ ion has a d10 configuration, and all the eg orbitals are filled. To excite an electron to a higher level, such as the 4p orbital, photons of very high energy are necessary. This energy corresponds to very short wavelengths in the ultraviolet region of the spectrum. No visible light is absorbed, so the eye sees no change, and the compound appears white or colorless. A solution containing [Cu(CN)2]−, for example, is colorless. On the other hand, octahedral Cu2+ complexes have a vacancy in the eg orbitals, and electrons can be excited to this level. The wavelength (energy) of the light absorbed corresponds to the visible part of the spectrum, and Cu2+ complexes are almost always colored—blue, blue-green violet, or yellow.

Magnetism in Coordination Complexes

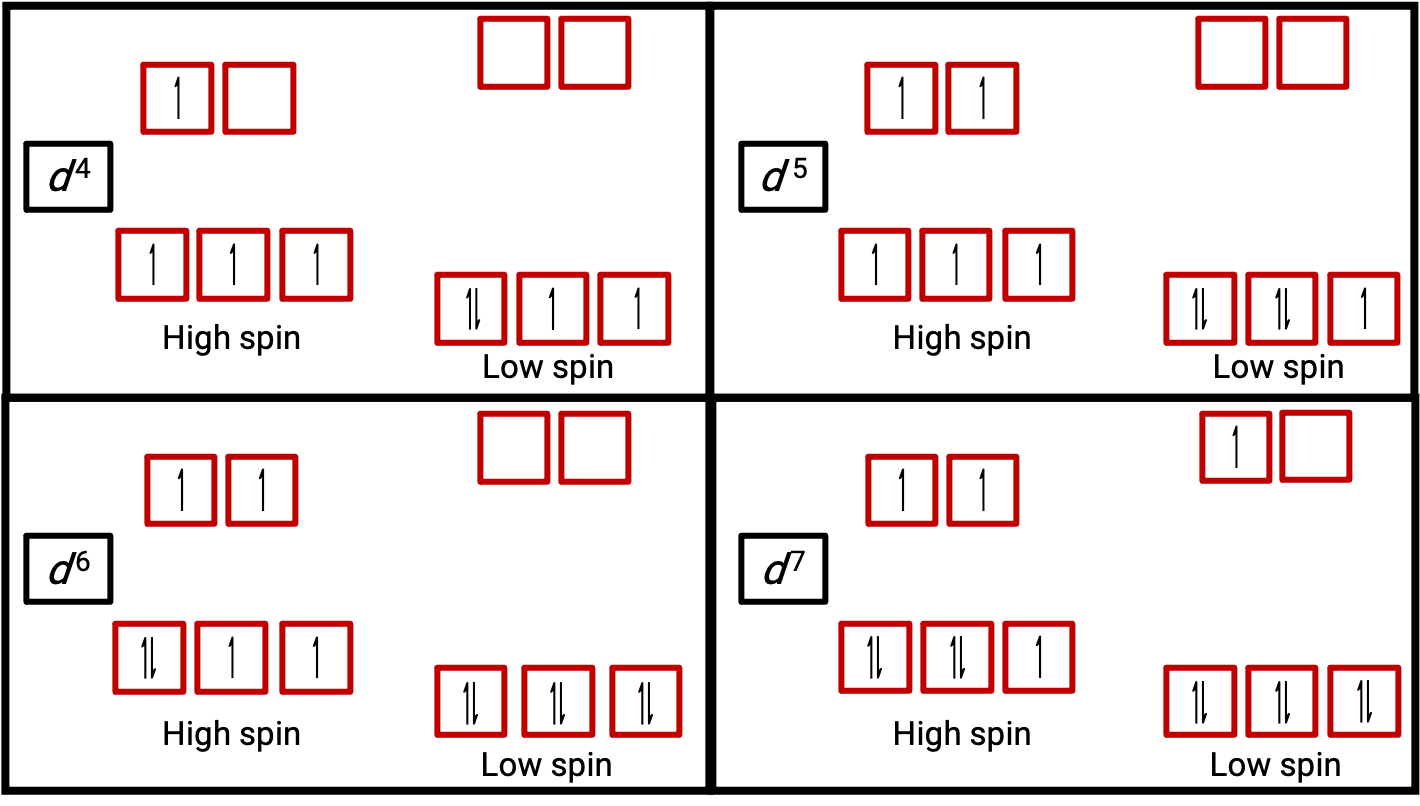

Experimental evidence of magnetic measurements supports the theory of high- and low-spin complexes. Molecules such as O2 that contain unpaired electrons are paramagnetic. Paramagnetic substances are attracted to magnetic fields. Many transition metal complexes have unpaired electrons and hence are paramagnetic. Molecules such as N2 and ions such as Na+ and [Fe(CN)6]4− that contain no unpaired electrons are diamagnetic. Diamagnetic substances have a slight tendency to be repelled by magnetic fields.

Figure 3. Orbital diagrams of the octahedral complexes in the high and low spin state for the d4, d5, d6, and d7 systems. This distinction can not be made for d1, d2, d3, d5, d8,d9 and d10 systems.

When an electron in an atom or ion is unpaired, the magnetic moment due to its spin makes the entire atom or ion paramagnetic. The size of the magnetic moment of a system containing unpaired electrons is related directly to the number of such electrons: the greater the number of unpaired electrons, the larger the magnetic moment. Therefore, the observed magnetic moment is used to determine the number of unpaired electrons present. The measured magnetic moment of low-spin d6 [Fe(CN)6]4− confirms that iron is diamagnetic, whereas high-spin d6 [Fe(H2O)6]2+ has four unpaired electrons with a magnetic moment that confirms this arrangement (Figure 2).

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section19.3: Spectroscopic and Magnetic Properties of Coordination Compounds.