Source:

Alexandra Duncan, GTA, Praxis Clinical, New Haven, CT

Tiffany Cook, GTA, Praxis Clinical, New Haven, CT

Jaideep S. Talwalkar, MD, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Providing comfortable speculum placement is an important skill for providers to develop, since the speculum is a necessary tool in many gynecological procedures. Patients and providers are often anxious about the speculum exam, but it is entirely possible to place a speculum without patient discomfort. It's important for the clinician to be aware of the role language plays in creating a comfortable environment; for instance, a provider should refer to the speculum "bills" rather than "blades" to avoid upsetting the patient.

There are two types of speculums: metal and plastic (Figure 1). This demonstration utilizes plastic, as plastic speculums are most commonly used in clinics for routine testing. When using a metal speculum, it's recommended to use a Graves speculum if the patient has given birth vaginally, and a Pederson speculum if the patient has not. Pederson and Graves speculums are different shapes, and both come in many different sizes (medium is used most often). Prior to placing a metal speculum, it is helpful to perform a digital cervical exam to assess for the appropriate speculum size. The depth and direction of the cervix is estimated by placing one finger into the vagina. If the patient's cervix can be located while the patient is seated, it is likely that the patient has a shallow vagina, and therefore should be most comfortable with a short metal speculum.

Figure 1. A photograph of commercially available speculums in different sizes.

Plastic speculums are all shaped like Pederson metal speculums and come in different sizes. To assess the appropriate size for a plastic speculum, the examiner places two fingers in the patient's vagina, palm down, and tries to separate the fingers: if there is no space between the fingers, a small plastic speculum should be used; if there is space between the fingers, a medium one should be used. The exam should never be performed with a large speculum (as it is significantly longer) without first determining the length of the vaginal canal.

The speculum is used to perform the Papanicolaou test as part of cervical cancer screening examinations. Cervical cancer was once the leading cause of cancer deaths for women in the United States, but in recent decades the number of cases and deaths has declined significantly1. This change is credited to the discovery made by Georgios Papanicolaou in 1928 that cervical cancer could be diagnosed by vaginal and cervical smears. The Pap test, as it is now called, detects abnormal cells in the cervix, both cancerous and pre-cancerous. Current guidelines for recommended screening intervals can be found through the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) website2.

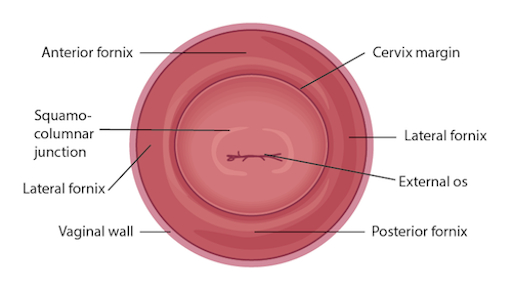

The test can be performed using either 1) a conventional glass slide and fixative with a spatula and endocervical brush (the traditional "Pap smear") or 2) the more commonly utilized liquid-based cytology with a cervical broom or a spatula and endocervical brush (Figure 2). No matter what tools are used, the samples are collected from just inside the external os and the squamocolumnar junction, or transition zone around the os (Figure 3). This video demonstrates the spatula and endocervical brush with liquid-based cytology, as the liquid preparation is a more effective technique for the detection of cervical lesions, and the spatula and endocervical brush improve specimen collection.

Figure 2. Pap smear tools. Shown in sequence are: a liquid cytology canister, cervical broom, spatula, and endocervical brush.

Figure 3. Diagram of the cervix withrelevant structures labeled.

Physical Examinations II