7.7:

The de Broglie Wavelength

If electrons are particles, then when a beam of electrons passes through two closely spaced slits, it is expected that two smaller beams of electrons should emerge and produce two bright stripes with darkness in between.

Initially, with only a few electrons, localized spots appear randomly on the screen. This suggests particle-like behavior.

However, as more and more electrons pass through the slits, an interference pattern — the hallmark of wave-like behavior — emerges. How is this possible?

Recall that the Bohr model proposed that the electron is a particle that orbits the nucleus. The French physicist Louis de Broglie postulated that the electron can exhibit wave properties. He suggested that the electron behaves as a circular standing wave with a wavelength, lambda.

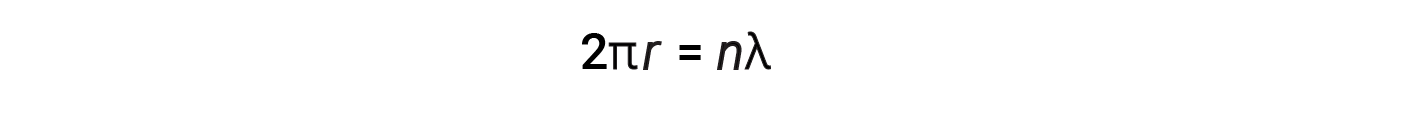

The circumference of each orbit contains an integer number of wavelengths. Certain points on the wave have zero amplitude —these are nodes.

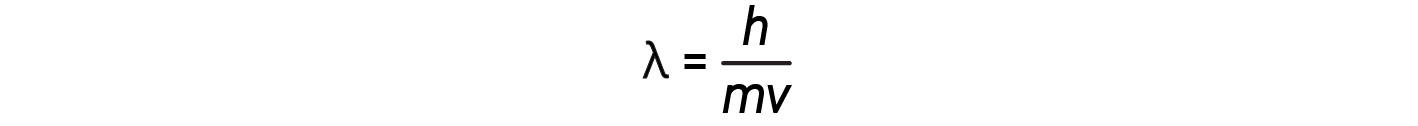

De Broglie proposed the following relation, in which the wavelength of the electron depends on its mass and velocity, with h being Planck’s constant. The greater the velocity of the electron, the shorter its wavelength.

The de Broglie hypothesis extends to all matter, and these waves are called ‘matter waves’. However, large, macroscopic objects, such as a golf ball, do not appear as waves. If we apply the de Broglie relation, the tiny value of Planck’s constant divided by the mass and velocity of the golf ball reveals an extremely small wavelength that is too small to observe.

However, for subatomic particles with extremely small masses — like electrons — their wave nature can’t be ignored.

When X-rays pass through a crystal, the waves are diffracted, and a distinctive interference pattern is obtained that reveals the arrangement of atoms in the crystal. This is the laboratory technique known as X-ray diffraction.

If a similar experiment is performed by passing electrons through the crystal instead of X-rays, a similar behavior is observed. This is experimental evidence that electrons are particles that demonstrate wave-like behavior.

7.7:

The de Broglie Wavelength

In the macroscopic world, objects that are large enough to be seen by the naked eye follow the rules of classical physics. A billiard ball moving on a table will behave like a particle; it will continue traveling in a straight line unless it collides with another ball, or it is acted on by some other force, such as friction. The ball has a well-defined position and velocity or well-defined momentum, p = mv, which is defined by mass m and velocity v at any given moment. This is the typical behavior of a classical object.

When waves interact with each other, they show interference patterns which are not displayed by macroscopic particles, like the billiard ball. However, by the 1920s, it became increasingly clear that very small pieces of matter follow a different set of rules from large objects. In the microscopic world, waves and particles are inseparable.

One of the first people to pay attention to the special behavior of the microscopic world was Louis de Broglie. He questioned that if electromagnetic radiation can have particle-like character, can electrons and other submicroscopic particles exhibit wavelike character? De Broglie extended the wave-particle duality of light that Einstein used to resolve the photoelectric-effect paradox to material particles. He predicted that a particle with mass m and velocity v (that is, with linear momentum p) should also exhibit the behavior of a wave with a wavelength value λ, given by this expression in which h is Planck’s constant:

This is called the de Broglie wavelength. Where Bohr had postulated the electron as being a particle orbiting the nucleus in quantized orbits, de Broglie argued that Bohr’s assumption of quantization could be explained if the electron is instead considered a circular standing wave. Only an integer number of wavelengths could fit exactly within the orbit.

If an electron is viewed as a wave circling around the nucleus, an integer number of wavelengths must fit into the orbit for this standing wave behavior to be possible.

For a circular orbit of radius r, the circumference is 2πr, and so de Broglie’s condition is:

where n = 1, 2, 3, and so forth. Shortly after de Broglie proposed the wave nature of matter, two scientists at Bell Laboratories, C. J. Davisson and L. H. Germer, experimentally demonstrated that electrons could exhibit wavelike behavior. This was demonstrated by aiming a beam of electrons at a crystalline nickel target. The spacing of the atoms within the lattice was approximately the same as the de Broglie wavelengths of the electrons being aimed at it, and the regularly spaced atomic layers of the crystal served as ‘slits,’ which is used in other interference experiments.

Initially, when only a few electrons were recorded, a clear particle-like behavior was observed. As more and more electrons arrived and were recorded, a clear interference pattern emerged, which is the hallmark of wavelike behavior. Thus, it appears that while electrons are small localized particles, their motion does not follow the equations of motion implied by classical mechanics. Instead, their motion is governed by a wave equation. Thus, the wave-particle duality first observed with photons is a fundamental behavior, intrinsic to all quantum particles.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 6.3: Development of Quantum Theory.