Summary

BM-PROMA 是一种有效可靠的多媒体诊断工具,可为数学学习障碍儿童提供完整的认知特征。

Abstract

学习数学是一个复杂的过程,需要发展多个域通用和特定域的技能。因此,许多儿童难以保持年级水平并不出人意料,当这两个领域的几个能力受到损害时,这变得特别困难,例如数学学习障碍(MLD)。令人惊讶的是,虽然MLD是影响学童的最常见的神经发育障碍之一,但现有的大多数诊断仪器不包括对域名一般和特定领域技能的评估。此外,很少有计算机化。据我们所知,没有适合讲西班牙语的儿童的这些功能的工具。本研究的目的是描述使用BM-PROMA多媒体电池诊断西班牙MLD儿童的程序。BM-PROMA 有助于对这两个技能领域的评估,为此目的包括的 12 项任务都是基于经验证据的。展示了BM-PROMA及其多维内部结构的强大内部一致性。BM-PROMA 被证明是在初等教育期间诊断患有 MLD 的儿童的适当工具。它为孩子提供了广泛的认知特征,这不仅与诊断相关,而且与个性化教学规划相关。

Introduction

初等教育的关键目标之一是获得数学技能。这些知识是非常相关的,因为我们都在日常生活中使用数学,例如,计算超市1,2的变化。因此,数学成绩不佳的后果超出了学术范畴。在社会一级,人口中数学表现不佳的普遍现象给社会造成损失。有证据表明,人口中糟糕的数字技能的提高为一个国家节省了大量开支。在个人层面上也有负面后果。例如,那些数学技能水平低的人,职业发展欠佳(例如,低薪体力职业的就业率较高,失业率较高)4、5、6,经常报告对学者的负面社会情绪反应(例如焦虑、对学术动机低)7、8,并且往往比平均数学成就为9的同龄人表现出较差的身心健康。数学学习障碍(MLD)的学生表现非常差,持续10,11,12。因此,他们更有可能遭受上述后果,特别是如果这些没有及时诊断13。

MLD是一种神经生物学障碍,其特点是学习基本数值技能严重受损,尽管有足够的智力能力和学校教育14。虽然这一定义被广泛接受,但鉴定的文书和标准仍在讨论之中。MLD诊断缺乏普遍协议的一个很好的例证是报告的流行率,从3到10%16,17,18,19,20,21。诊断的这种困难源于数学知识的复杂性,这就要求在22、23年学习多个域名一般和域特定技能的组合。MLD儿童表现出非常不同的认知特征,有广泛的赤字星座14,24,25,26,27。在这方面,有人建议,需要通过涉及不同数字表示(即口头、阿拉伯语、类比)和算术技能的任务进行多维评估。

在小学时,MLD的症状多种多样。在域名特定技能方面,人们不断发现,许多 MLD 学生在基本数值技能方面表现出困难,例如快速准确地识别阿拉伯数字28、29、30,比较震级31、32或表示数字行33、34。小学生在理解概念知识方面也表现出困难,如地点值35、算术知识36,或通过有序序列37测得的平度。关于域名一般技能,特别注重工作记忆38、39和语言40在有和没有MLD的儿童数学技能的发展中的作用。在工作记忆方面,结果显示,MLD的学生在中央行政机构中表现出不足,尤其是在需要操纵数字信息41,42时。在MLD43,44的儿童中,也经常报告存在病毒空间短期记忆缺陷。语言技能是学习算术技能的先决条件,尤其是那些涉及高语言处理需求的技能。例如,语音处理技能(例如,语音意识和快速自动化命名(RAN)与小学时学到的基本技能密切相关,如数值处理或算术计算39、45、46、47。在这里,已经证明,语音意识和RAN的变化与个人在算术技能的差异,涉及管理口头代码42,48。鉴于 MLD 儿童的复杂状况,诊断工具最好包括评估域名一般技能和特定域位技能的任务,据报道,这些技能在这些儿童中往往存在缺陷。

近年来,为MLD开发了几种纸笔筛选工具。西班牙小学生最常用的是 a)埃瓦马泰利亚·巴泰利亚·马泰马蒂卡竞争中心(数学能力评价电池)49:b) 泰迪数学:数学残疾诊断评估测试(西班牙语改编)50:c)测试德埃卢阿西翁马特马蒂卡坦普拉纳德乌得勒支(TEMT-U)51,52, 乌得勒支早期算术测试53的西班牙语版本:d) 早期数学能力测试 (TEMA-3)54.这些文书衡量上述许多特定领域的技能:但是,他们都没有评估域名一般技能。这些仪器和一般纸和铅笔工具的另一个限制是,它们无法提供有关每个物品处理的准确性和自动性的信息。这只能用电脑电池。然而,很少有应用程序已经开发为计算障碍诊断。第一个计算机化的工具,旨在识别儿童(6至14岁)与MLD是Dyscalculia筛选器55。几年后,基于网络的DyscalculiUm56的开发目的相同,但侧重于16岁以后教育中的成年人和学习者。虽然仍然有限,但近年来对MLD诊断的计算机化工具设计的兴趣与日俱增。所提及的工具都没有为西班牙儿童标准化,其中只有一个工具 -MathPro 测试57- 包括域名一般技能评估。鉴于识别数学成就低的儿童,特别是那些有MLD的儿童的重要性,以及西班牙人口缺乏计算机化仪器,我们提出了一个多媒体评估协议,其中包括域名通用和特定领域的技能。

Subscription Required. Please recommend JoVE to your librarian.

Protocol

这项议定书是根据拉古纳大学 "双星动物 研究伦理和动物福利委员会"提供的准则执行的。

注: 巴泰利亚多媒体公司 使用 Unity 2.0 专业版和 SQLITE 数据库引擎开发了61。 BM-PROMA 包括 12 个子测试:8 个子测试以评估特定域的技能,4 个子测试以评估域名一般流程。对于每个子测试,由动画类人机器人口头提供说明,并在测试阶段之前进行演示和两次训练试验。下面将介绍每个任务的应用程序协议,并举一个示例。

1. 实验设置

- 使用以下包容性标准:二年级至六年级初等教育的儿童:以西班牙语为母语。

- 使用以下排除标准:有神经、智力或感官缺陷史的儿童。

- 安装多媒体电池,用于评估数学中的认知和基本技能。BM-PROMA 使用单个文件进行分发。此文件是一个自动安装程序,允许用户选择安装目的地。安装程序检测工具的先前版本,并警告用户由于覆盖而可能的数据丢失。该安装在 Windows"开始"菜单中创建快捷方式。此外,安装程序还提供批量文件(在 Windows 中称为.bat文件),以自动执行数据库备份过程。该工具以 800x600 像素的分辨率在全屏幕模式下运行。该工具不能在窗口模式下运行。

- 在评估学生之前,将其数据添加到学生数据库。孩子注册后,点击学生列表中的相关条目进行选择。任务由考官或孩子随机选择。一旦检查员或孩子点击任务,任务就开始了。任务完成后,工具返回任务选择菜单。学生完成的任务在菜单中不再可见。一旦会话开始,任务之间就没有中断。

- 测试儿童在三个半小时内进行2级和3级考试,在两次45分钟的课程中测试4至6年级儿童。在不同的日子举行会议。在安静的房间里管理 BM-PROMA。让学生使用耳机听指示并记录他们的口头反应:考官还使用耳机监控任务。在某些情况下,审查员必须使用鼠标记录任务的结果:在其他方面,学生使用鼠标完成任务,并自动记录响应。

- 示范和培训试验。对于所有任务,在测试阶段之前,有说明(机器人口头介绍任务说明)、建模(机器人以示例逐步模拟任务)和练习试验(允许儿童进行多达两次有反馈的练习试验)。

2. 域特定子测试

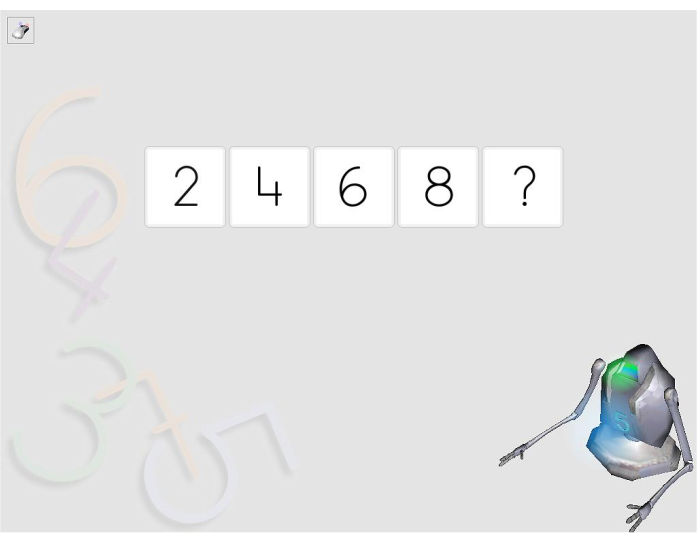

- 缺失号码 (图1)

- 在此任务中,请儿童从水平显示的 4 个单位和两位数的系列数字中说出缺失的数字。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须大声说出丢失号码的名称:二、四、六、八和(暂停)十。所以,缺少的数字是十。现在,自己试试"。

- 共呈现 18 个系列:6 个数字上升顺序(按给定数量级增加的系列值数字添加到上一个数字中),6 个以数字降序排列(以给定数量级减去的系列值减少的数字),以及 6 个数字级升序(需要多个算术操作才能解决它们, 在这种情况下,乘法和添加)。考官使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。

- 根据正确响应的总数计算分数。

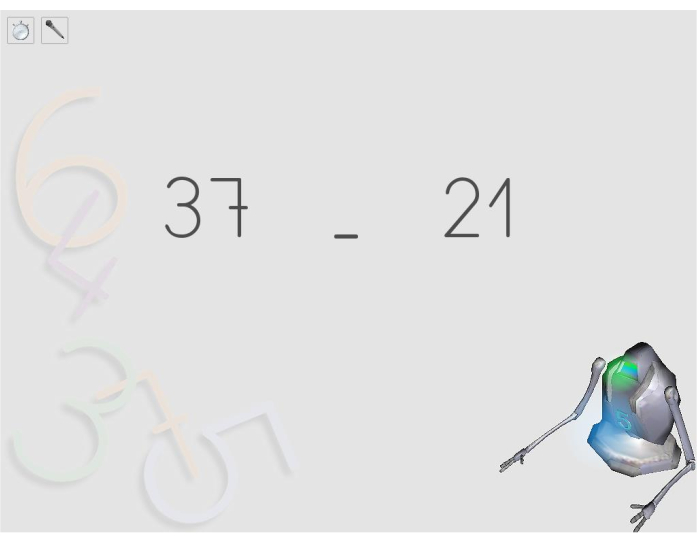

- 两位数比较 (图2)

- 在此任务中,在计算机屏幕上显示 40 对两位数的数字。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,仔细看看这两个数字。你必须选择最大的数字。要做到这一点,你必须比较两个数字,并大声说出最大的一个数字的名字。看看这两个数字三十七比二十一大。所以,我会说/三十七/。尽量尽快完成任务,而不要弄错。现在,自己试试"。

- 要求孩子大声说出每对数字较大的数字。语音键记录了孩子的反应时间(RT),之后检查员使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。

注:根据先前的研究, 62 、 63 、单位十年兼容性(兼容与不兼容)和十年和单位距离(小 [ 1 - 3 ] 与大 [ 4 - 8 ] )纵。 - 根据正确解决的刺激的 RT 计算分数。

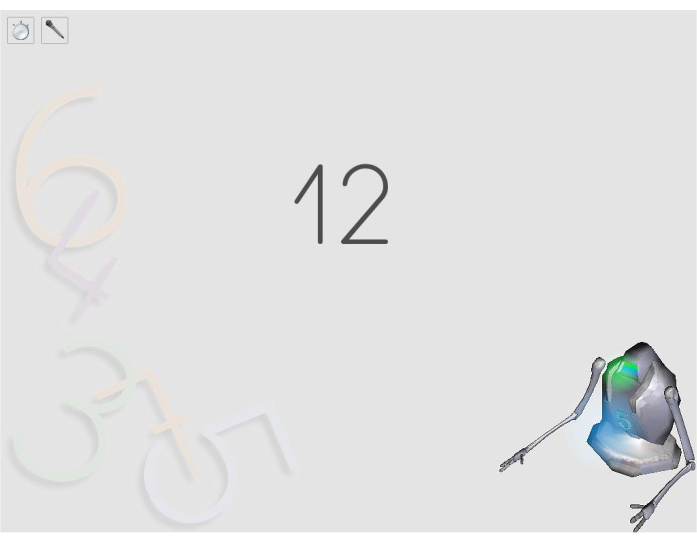

- 阅读数字 (图3)

- 在计算机屏幕上一次显示 30 个阿拉伯数字(10 个单位数数字、10 个两位数数字和 10 个三位数数字)。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须大声说出屏幕上出现的数字。看看这个数字在这里,你必须说/十二/,因为这是屏幕上的数字的名称。尽量尽快完成任务,而不要弄错。现在,自己试试"。

- 要求孩子尽快大声朗读,不要犯错。语音键注册了孩子的 RT,之后检查员使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。

- 根据正确读取的刺激的 RT 计算分数。

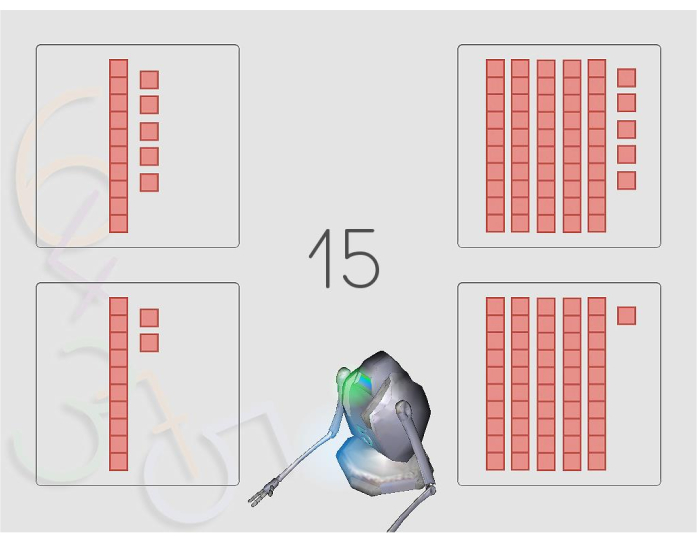

- 位置值 (图4)

- 衡量学生对阿拉伯语号码系统的了解。在计算机屏幕中央显示 12 个两位数的阿拉伯数字,屏幕每个角落都设有一个答案选项(总共四个选项)。每个选项都由几十个单元和块(十个单元分组成一个块)表示数量。对于每个项目,四个选项中只有一个是正确的。不正确的选项由与 a) 十中的正确选项重合的表示组成;b) 单位;或 c) 十和单位,但反转(例如,对于数字"15",不正确的选项表示 12,35 和 51)。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,我们有一个数字和四张图片。您必须单击正确表示数字的图片。我会选择第一个,因为酒吧等于十,方块等于五个单位。现在,自己试试"。

- 根据正确响应的总数计算分数。

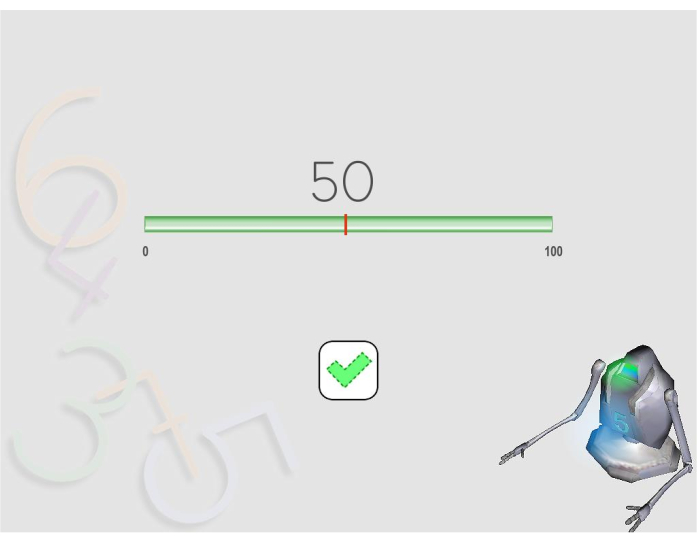

- 数字行 0-100 和 0-1000 任务 (图 5)

注:使用电脑改编的纸和铅笔原装64。- 在这项任务中,让孩子使用计算机鼠标在 15 厘米的号码线上放置给定号码。对于前 20 个项目,行左端值为 0,右端值为 100。对于以下 22 个项目,右端值为 1000。

- 在 0-100 行上展示以下项目:2、3、7、11、14、18、23、37、41、45、56、60、67、71、75、86、89、91、95 和 99。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须把数字放在你认为应该去的地方。看看这条线它从零开始,到一百点结束。你必须把五十号放在这里。为此,单击并按住数字下的红线,将其拖到正确位置。你知道我为什么把号码掉在这里吗?它在中间,因为五十是一百的一半。现在,自己试试"。

- 按照最初的任务,在分布的低端对数字进行过度调高,在 0 到 30 之间有 7 个数字。为 0-1000 行提供的项目是: 2, 11, 67, 99, 106, 162, 221, 325, 388, 450, 492, 511, 591, 643, 677, 755, 799, 815, 867, 910 和 988.与上述研究一样,低于100的值被过度采样。

- 根据百分比误差的绝对值计算分数(|估计数 - 估计数量/估计规模|)。

- 算术事实检索 (图6)

- 要求儿童解决 66 个单位数算术问题,包括 24 个加法、24 个乘法和 18 个减法,以单独的方块表示。不包括领带问题(例如,3+3)和包含 0 或 1 的问题作为操作或答案。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须解决你头脑中的计算问题。在第一个,正确的答案是三个。默默地完成任务,大声告诉我答案。尽量尽快解决任务,不要弄错。现在,自己试试。

- 在计算机屏幕上一次一个水平地显示问题。回应是口头的。语音键注册了孩子的 RT,之后检查员使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。

- 根据正确解决的刺激的 RT 计算分数。

- 算术原理 (图7)

- 呈现 24 对相关的两位数操作(12 对添加和 12 对乘法)。在每对中,一个项目正确解答,另一个项目未解(例如,5×5×10→5×6+?

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须大声说出第二次操作的结果。仔细查看这两个计算。第一个已经解决了,但第二个还是需要解决的。五加五等于十,然后五加六等于十一。当我告诉你开始,在沉默中解决任务,然后大声说答案。尽量尽快解决任务,不要弄错。现在,自己试试"。

- 请孩子们大声说出未解决手术的结果。语音键记录了孩子的反应时间(RT),之后检查员使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。

- 根据正确解决的刺激的 RT 计算分数。

3. 域名一般子测试

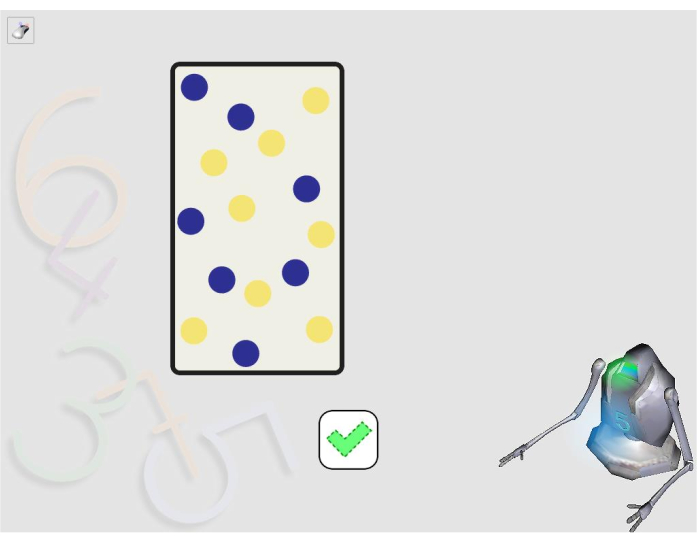

- 计数跨度 (图8)

注:此任务是工作内存计数任务65的改编。- 让孩子们大声数一数黄点和蓝点的一系列牌上的黄点数。请他们回忆一下套卡上每张卡上的黄点数量。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,我们有一些牌。每张牌都有蓝色和黄色的圆点。你必须计算并记住每张卡上的黄点数。首先,我们将计算第一张卡上有多少个黄点。卡片上有两个黄点。然后,我们将计算第二张卡上的所有黄点。卡上有八个黄点。现在,由于第一张牌上有两个黄点,第二张牌上有八个黄点,你不得不大声说出数字二和八。现在,自己试试"。

- 将套路长度从2张增加到5张,让孩子们三次尝试进入新的难度水平。考官使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。

- 当孩子未能在给定难度级别正确回忆两套时,结束测试。

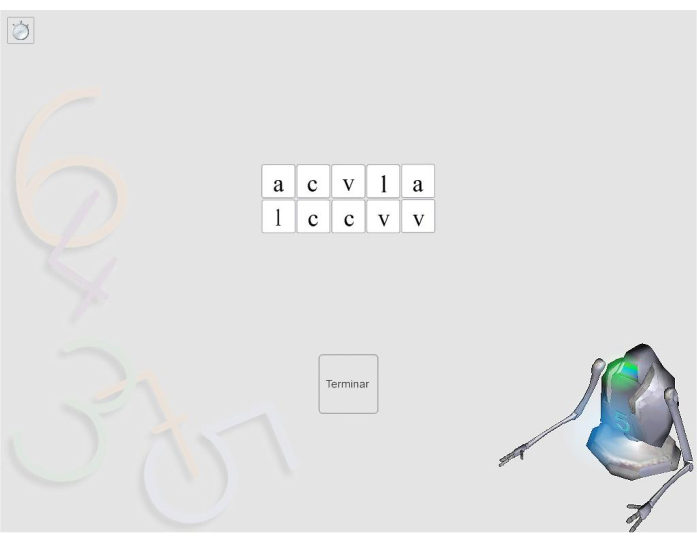

- 快速自动命名 - 字母 (RAN-L) (图 9)

注:此任务是对称为快速自动命名66 的技术的改编。RAN-L 由五行和计算机屏幕上的 10 列五个字母组成。- 要求孩子尽快从左到右、从上到下说出字母名称。在由两行和五列组成的图表中提供十个练习项目。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须说出屏幕上出现的字母。重复它们并不重要。因此,我们必须说:/a/,/c/,/v/,/n/,/a/,/n/,/c/,/c/,/v//尽量从左到右、从上到下尽快命名字母。现在,自己试试"。

- 使用花费的时间命名所有 50 个字母作为分数。要使分数分布正常化,将分数转换为每分钟的字母数。

- 维苏空间工作记忆 (图10)

注:此任务是科西块攻丝任务67的计算机化改编。- 在屏幕中央显示一个 3x3 板。在每个试验中,连续打开和关闭某些方块。

- 通过单击已更改颜色的方块,让孩子按正确的顺序重复序列。在 50% 的案例中,要求他们按相同的顺序执行,而其他 50% 的案例则以相反顺序执行。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你会看到一些正方形亮了起来。你必须记住哪些广场亮了,它们按顺序亮起。然后,您必须按相同的顺序按方块以重复序列。现在,仔细观察,按相同的顺序按方块"。

- 将试验长度从 2 块增加到 5 块。给孩子们三次尝试,让孩子们更上一层楼。

- 当孩子未能在给定难度级别正确回忆两套时,结束测试。考官使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。根据给出的正确答案数量计算分数。

- 电话删除

注:此任务包括 15 个双音节单词:5 个带辅音元音 (CV) 第一个音节结构,5 个带辅音-元音调谐体 (CVC) 第一个音节结构,5 个带辅音-谐音元音 (CCV) 第一个音节结构。- 对孩子说一句话,让他们重复一遍,省略第一声。

- 让机器人说:"在这个游戏中,你必须删除每个单词的第一个声音。如果您听到单词 /塔德/ (晚), 你必须删除声音 /t/.所以,你会说/阿德/。现在,自己试试"。

- 考官使用鼠标按钮记录答案是否正确。根据正确响应的总数计算分数。

Subscription Required. Please recommend JoVE to your librarian.

Representative Results

为了测试这种诊断工具的效用和有效性,在大规模样本中对其心理特征进行了分析。共有933名西班牙小学生(男孩=508,女孩=425; M年龄 = 10 岁 ,SD = 1.36), 从 2 年级到 6 年级 (2 年级, N = 169 [89 男孩]; 3 年级, N = 170 [89 男孩]; 4 年级, N = 187 [106 男孩]; 5 年级, N = 203 [113 男孩]; 6 年级, N= 204 [110 男孩]参加了这项研究。这些儿童来自圣克鲁斯-德特内里费市城市和郊区的国立和私立学校。学生分为两组:a) 在标准化算术测试中得分在或低于第16百分位的 MLD 儿童(2 年级、N =14;3 年级、N =35;4 年级、N =11;5 年级、N = 47;6 年级、N = 42 年级);和 b) 通常在同一测试中得分在 40 百分位或以上的儿童 (2 年级、 N = 130; 3 年级, N =124; 4 年级, N =149; 5 年级, N = 110; 6 年级, N = 105) 。

该工具结构的多维性通过确认因子分析(CFA)测试,使用R68中的熔岩包。假设了BM-PROMA的五因子模型。包含所有域一般任务的认知因素是预料之中的,因为域名一般技能对数学性能的贡献不同于域特定技能69,70。由于算术和基本数值技能涉及不同的认知和大脑相关性,因此也只对算术任务进行算术因子分组。最后,遵循三重代码模型72,根据任务是否涉及口头、阿拉伯语或类比表示,对数字任务进行三个因素的分组。

有关内部一致性的证据是使用克朗巴赫的阿尔法进行评估的。克朗巴赫的阿尔法是计算所有措施,并提出了每个年级和整个参与者样本。内部一致性值在α ≥ .80 时被认为是优秀的,在α ≥ .70 和 <.80 时良好,在α ≥ .60 和 <.70 时可接受,在α ≥ .50 时差时为 0.50 和 < .60 时为差值,在α < .5073时不可接受。

模型适合性是使用强大的最大可能性 (RML) 估计方法估计的,并使用以下索引74,75:标准化根平均方 (SRMS ≤.08), 奇方(+2,p> 0 进行评估 5)、塔克-刘易斯指数(TLI ≥ .90)、比较拟合指数(CFI ≥ 。90)、近似基本平均方误差(RMSA ≤.06)和复合可靠性(+≥ 。60)。检查了修改指数。

对描述性统计数据进行了审查,并提交 到表1中。结果显示,数据分布正常,股指和偏斜指数分别低于10.00和3.00。

| 措施 | 2 级 | 3 级 | 4 级 | 5 级 | 6 级 | 总 | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| 缺少数字 | 3.81 | 3.29 | 5.79 | 3.49 | 7.68 | 3.15 | 7.56 | 3.50 | 8.33 | 2.98 | 6.67 | 3.65 | |

| 两位数的数字比较 | 2.02 | .54 | 1.78 | .35 | 1.50 | .24 | 1.46 | .15 | 1.44 | .15 | 1.62 | .38 | |

| 阅读数字 | 1.14 | .27 | 1.27 | .23 | 1.14 | .21 | 1.17 | .18 | 1.21 | .20 | 1.24 | .24 | |

| 位置值 | 8.83 | 3.19 | 9.83 | 2.89 | 10.58 | 1.62 | 10.33 | 1.95 | 10.89 | 1.49 | 10.14 | 2.38 | |

| 数字行 0-100 | .11 | .06 | .07 | .30 | .06 | .02 | .05 | .02 | .05 | .19 | .07 | .04 | |

| 数字行 0-1000 | .18 | .09 | .13 | .06 | .09 | .04 | .09 | .04 | .07 | .02 | .11 | .06 | |

| 添加事实检索 | 5.11 | 4.42 | 7.03 | 5.24 | 11.15 | 5.74 | 10.27 | 5.82 | 12.03 | 5.30 | 9.32 | 5.93 | |

| 减法事实检索 | 4.36 | 3.79 | 5.78 | 4.66 | 8.94 | 4.53 | 8.64 | 4.84 | 9.76 | 4.31 | 7.66 | 4.89 | |

| 乘法事实检索 | 2.92 | 3.27 | 6.32 | 4.97 | 11.48 | 5.67 | 10.10 | 5.90 | 11.49 | 5.43 | 8.72 | 6.13 | |

| 算术原理 | 8.33 | 4.71 | 8.05 | 3.41 | 8.95 | 3.80 | 9.38 | 4.01 | 10.78 | 4.56 | 9.21 | 4.22 | |

| 计数跨度 | 4.57 | 2.35 | 5.45 | 2.65 | 6.41 | 2.56 | 6.43 | 2.59 | 7.03 | 2.49 | 6.05 | 2.67 | |

| 维苏空间工作记忆 | 6.26 | 2.74 | 7.30 | 2.62 | 8.18 | 2.33 | 8.46 | 2.42 | 9.27 | 2.23 | 7.98 | 2.66 | |

| 电话删除 | 9.34 | 4.78 | 10.96 | 4.60 | 12.64 | 2.83 | 12.62 | 2.92 | 12.61 | 3.37 | 11.73 | 3.94 | |

| 快速自动化命名 - 字母 | 1.37 | .32 | 1.53 | .31 | 1.72 | .31 | 1.80 | .35 | 1.87 | .36 | 1.68 | .38 | |

表1:每个等级的BM-PROMA子测试的描述性统计数据。

除数值工作内存外,每个测量的内部一致性均在 表 2中显示。结果表明,每个年级的大部分措施的α均超过0.70,表明大多数任务的内部一致性良好。

| 措施 | 2 级 | 3 级 | 4 级 | 5 级 | 6 级 | 总 | ICL | |

| 缺少数字 | .841 | .843 | .807 | .858 | .801 | .861 | 1 | |

| 两位数的数字比较 | .891 | .925 | .916 | .868 | .866 | .895 | 1 | |

| 阅读数字 | .861 | .830 | .849 | .892 | .753 | .855 | 1-2 | |

| 位置值 | .843 | .864 | .722 | .686 | .740 | .809 | 1-3 | |

| 数字行 0-100 | .825 | .748 | .658 | .547 | .678 | .801 | 1-4 | |

| 数字行 0-1000 | .806 | .820 | .763 | .743 | .729 | .867 | 1-2 | |

| 添加事实检索 | .852 | .879 | .885 | .892 | .856 | .898 | 1 | |

| 减法事实检索 | .826 | .880 | .846 | .868 | .823 | .876 | 1 | |

| 乘法事实检索 | .811 | .861 | .867 | .881 | .853 | .901 | 1 | |

| 算术原理 | .586 | .734 | .844 | .742 | .866 | .821 | 1-4 | |

| 维苏空间工作记忆 | .741 | .726 | .660 | .695 | .699 | .747 | 1-3 | |

| 电话删除 | .918 | .933 | .835 | .853 | .899 | .911 | 1 | |

| 注意。ICL = 内部一致性级别;1 = 优秀;2 = 好;3 = 可接受;4 = 穷人, 5 = 不能接受。 | ||||||||

表2:克朗巴赫是每个年级所有措施的系数。

为了确认BM-PROMA的因子结构,使用RML估计方法进行了终审法院。拟合指数建议充分适合为数据提出的五因子模型:=2 = 29.930 df = 67,p = .000;CFI = .948;TLI = .930;RMSEA = .053, 90% CI = [.046-.061];SRMR = .046;F1 , = 0.50 ;F2, + = .75;F3, + + .80;F4, + + .81;F5, = = .46 (图 11)。

图11:BM-PROMA的确认因子分析。 注意。F1 = 阿拉伯数字表示因子;F2 = 类比表示因子;F3 = 语言表示因素;F4 = 算术因子;F5 = 认知因子;RAN-L = 快速自动化命名字母;VWM = 维苏空间工作记忆;CS = 计数跨度;Pd = 电话删除;AP = 算术原理;MFR+ 乘法事实检索;AFR = 添加事实检索;SFR = 减法事实检索;跨国公司 = 两位数数字比较;RN = 阅读数字;NL-100 = 数字行 0-100;NL-1000 = 数字行 0-1000;光伏 = 地方价值;MN = 缺少号码。请单击此处查看此图的较大版本。

该工具的多维方法得到确认。BM-PROMA 中包含的任务包含五个因素:1) 在"阿拉伯数字表示因子"上加载的缺失数值任务:2) 数字线估计 0-100 和数字线估计 0-1000 任务加载在"模拟表示因子"上:3) 加载在"语言表示因子"上的两位数数字比较和读数任务:4) 计算原理、添加事实检索、乘法事实检索和减法事实检索任务加载在"算术因子"上:和 5) 计数跨度、音素删除、RAN-L 和在"认知因子"上加载的维苏空间工作记忆任务。

为了检查不同等级的测量差异,我们将样本分成两组。第一组由2-3年级(A组)的学生组成。第二组由4-6年级(B组)的学生组成。学生被重新组合,以增加样本量和尽量减少组数,作为样本特征,组数比较,和模型复杂性都影响测量不一致77。比较了四个嵌套模型:配置(模型形式的等价)、公制(因子加载等价)、缩放(项目拦截等价物)和严格(项目残余等价)。结果在表 3中显示,该表显示了不同组的配置、指标、缩放和严格不一致。

| 型 | χ2 | df | CFI | 特利 | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | [中菲 | 奥姆西 | ||

| 配置(结构) | 364.145 | 134 | .940 | .918 | .061 [.053 - . 068] | .051 | ||||

| 公制(加载) | 383.400 | 143 | .937 | .920 | .060 [.053 - .067] | .056 | - .003 | -.001 | ||

| 斯卡拉(拦截) | 383.845 | 152 | .939 | .927 | .057 [.050 - .064] | .056 | .002 | -.003 | ||

| 严格(残余) | 398.514 | 166 | .939 | .933 | .055 [.048 - .062] | .056 | .000 | -.002 | ||

| 注意。CFI = 比较适合指数;TLI = 塔克 - 刘易斯指数, RMSEA = 根平均方形近似误差; | ||||||||||

| CI = 置信区间;SRMR = 标准化根均值方形残余; •差异。 | ||||||||||

| 所有 +2 值在 p <.001 时都很重要。 | ||||||||||

表3:适合BM-PROMA测量不一致的指数。

最后,根据CFA分析得出的五个因素,对接收机操作特征(ROC)进行了分析,以研究BM-PROMA的诊断准确性。标准化的 普鲁埃巴·德·卡尔库洛·努梅里科 (算术计算测试)78 作为测试每个单一诊断措施(即因子)准确性的黄金标准。探讨了 ROC 曲线下的区域 (AUC > 。70)、灵敏度 (>.70) 和特异性 (> 。80) 值。结果显示,除F3(即语言表示因子)和F2(即类比表示因子)外,所有年级的所有系数均可接受的AUC(表4)。灵敏度和特异性值变化很大,灵敏度从 0.468 到 0.846 不等,特异性从 0.595 到 0.929 不等。这些结果表明,虽然所有指标都有助于数学能力的发展,但其效用因年级而异。

| 年级 | 因素 | AUC | 锡 | 斯普 |

| 2 级 | F1 | .912 | .808 | .857 |

| F2 | .902 | .785 | .929 | |

| F3 | .746 | .823 | .786 | |

| F4 | .906 | .846 | .929 | |

| F5 | .918 | .838 | .929 | |

| 3 级 | F1 | .762 | .734 | .714 |

| F2 | .736 | .645 | .800 | |

| F3 | .608 | .468 | .743 | |

| F4 | .753 | .605 | .771 | |

| F5 | .733 | .556 | .743 | |

| 4 级 | F1 | .719 | .745 | .727 |

| F2 | .694 | .597 | .727 | |

| F3 | .817 | .705 | .818 | |

| F4 | .775 | .691 | .818 | |

| F5 | .782 | .678 | .727 | |

| 5 级 | F1 | .855 | .764 | .809 |

| F2 | .810 | .736 | .745 | |

| F3 | .630 | .527 | .681 | |

| F4 | .835 | .745 | .809 | |

| F5 | .832 | .855 | .787 | |

| 6 级 | F1 | .839 | .686 | .714 |

| F2 | .776 | .648 | .738 | |

| F3 | .524 | .486 | .595 | |

| F4 | .891 | .848 | .905 | |

| F5 | .817 | .752 | .738 |

表4:每个等级的BM-PROMA子测试的诊断准确性。注意。F1 = 阿拉伯数字表示因子;F2 = 类比表示因子;F3 = 语言表示因素;F4 = 算术因子;F5 = 认知因子;AUC = 曲线下的区域;Sn = 敏感性;斯普 = 特异性。

图1:缺少数字任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图2:两位数比较任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图3:阅读数字任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图4: 放置值任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图5:数字线估计任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图6:算术事实检索任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图7:算术原理任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图8: 计数跨度任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图9: 快速自动化命名 - 字母任务 (RAN-L) 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

图10: 维苏空间工作内存任务请点击这里查看此图的较大版本。

Subscription Required. Please recommend JoVE to your librarian.

Discussion

患有MLD的儿童不仅有学业失败的危险,而且有精神情绪和健康障碍的风险,8、9和后来的就业剥夺4,5。因此,必须迅速诊断MLD,以便提供这些儿童所需要的教育支助。然而,诊断MLD是复杂的,由于多个域特定和域一般技能缺陷,导致紊乱22,23。BM-PROMA 是少数使用多维协议诊断患有 MLD 的小学生的计算机化工具之一,也是第一个对讲西班牙语的儿童进行标准化的工具。

本研究已证明BM-PROMA是一种有效和可靠的仪器。ROC 分析的结果很有希望,显示几乎所有因素和等级的 AUC 从 0.72 到 0.92 不等。这表明接受优秀的歧视79。F3 在 3 级、5 级和 6 级的支撑力最弱,4 级的 F2 获得 AUC < 。70。需要注意的是,我们只使用一种衡量标准作为黄金标准,并且它侧重于多位数计算技能:因此,这是一个非常有限的措施。黄金标准应反映所调查标准措施的内容,因此我们认为,在今后的研究中增加其他标准化国家评估,可以提高分类准确性。

虽然 BM-PROMA 是一个非常全面的工具,但未来版本将相关性地包括已发现在 MLD 儿童中受损的其他特定领域技能,例如,81岁幼儿的非符号比较任务和合理的数字操作或解决82、83岁年龄较大的儿童的算术单词问题。还必须纳入其他领域通用技能,似乎缺乏MLD,如抑制控制84。

尽管存在上述限制,但BM-PROMA是少数旨在识别有计算障碍儿童的软件之一,本研究已证明它是一种有效和可靠的仪器。内部结构代表工具的多维评估方法。它为孩子提供了广泛的认知特征,这不仅与诊断相关,而且与个性化教学规划相关。此外,其多媒体格式对儿童具有很强的激励作用,同时使评估程序更加容易。

Subscription Required. Please recommend JoVE to your librarian.

Disclosures

上述作者证明本研究没有经济利益或其他利益冲突。

Acknowledgments

我们感谢西班牙政府通过其 国家I+D+i计划 (西班牙经济和竞争力部国家研究计划)对项目参考的支持:PET2008_0225,第二作者为主要调查员;和康尼西特 - 智利 [方德西特定期诺1191589], 第一作者作为主要调查员。我们还感谢 ULL 视听联合 团队参与视频制作。

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Multimedia Battery for Assessment of Cognitive and Basic Skills in Maths | Universidad de La Laguna | Pending assignment | BM-PROMA |

References

- Henik, A., Gliksman, Y., Kallai, A., Leibovich, T. Size Perception and the Foundation of Numerical Processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 26 (1), 45-51 (2017).

- Henik, A., Rubinsten, O., Ashkenazi, S. The "where" and "what" in developmental dyscalculia. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 25 (6), 989-1008 (2011).

- OCDE. The High Cost of Low Educational Performance: The long-run economic impact of improving PISA outcomes. , Available from: www.oecd.org/publishingwww.sourceoecd.org/9789264077485 (2010).

- Ghisi, M., Bottesi, G., Re, A. M., Cerea, S., Mammarella, I. C. Socioemotional features and resilience in Italian university students with and without dyslexia. Frontiers in Psychology. 7, 1-9 (2016).

- Parsons, S., Bynner, J. Numeracy and employment. Education + Training. 39 (2), 43-51 (1997).

- Sideridis, G. D. International Approaches to Learning Disabilities: More Alike or More Different. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 22 (3), 210-215 (2007).

- Duncan, G. J., et al. School Readiness and Later Achievement. Developmental Psychology. 43 (6), 1428-1446 (2007).

- Wu, S. S., Barth, M., Amin, H., Malcarne, V., Menon, V. Math Anxiety in Second and Third Graders and Its Relation to Mathematics Achievement. Frontiers in Psychology. 3, 162 (2012).

- Reyna, V. F., Brainerd, C. J. The importance of mathematics in health and human judgment: Numeracy, risk communication, and medical decision making. Learning and Individual Differences. 17 (2), 147-159 (2007).

- Geary, D. C., Hoard, M. K., Nugent, L., Bailey, D. H. Mathematical cognition deficits in children with learning disabilities and persistent low achievement: A five-year prospective study. Journal of Educational Psychology. 104 (1), 206-223 (2012).

- Kaufmann, L., et al. Dyscalculia from a developmental and differential perspective. Frontiers in Psychology. 4, 516 (2013).

- Wong, T. T. Y., Chan, W. W. L. Identifying children with persistent low math achievement: The role of number-magnitude mapping and symbolic numerical processing. Learning and Instruction. 60, 29-40 (2019).

- Haberstroh, S., Schulte-Körne, G. Diagnostik und Behandlung der Rechenstörung. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 116 (7), 107-114 (2019).

- Kaufmann, L., von Aster, M. The diagnosis and management of dyscalculia. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international. 109 (45), 767-777 (2012).

- Murphy, M. M., Mazzocco, M. M., Hanich, L. B., Early, M. C. Children With Mathematics Learning Disability (MLD) Vary as a Function of the Cutoff Criterion Used to Define MLD. Journal of learning disabilities. 40 (5), 458-478 (2007).

- Ramaa, S., Gowramma, I. P. A systematic procedure for identifying and classifying children with dyscalculia among primary school children in India. Dyslexia. 8 (2), 67-85 (2002).

- Dirks, E., Spyer, G., Van Lieshout, E. C. D. M., De Sonneville, L. Prevalence of combined reading and arithmetic disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 41 (5), 460-473 (2008).

- Mazzocco, M. M. M., Myers, G. F. Complexities in Identifying and Defining Mathematics Learning Disability in the Primary School-Age Years. Annals of dyslexia. (Md). 53, 218-253 (2003).

- Barahmand, U. Arithmetic Disabilities: Training in Attention and Memory Enhances Artihmetic Ability. Research Journal of Biological Sciences. 3 (11), 1305-1312 (2008).

- Reigosa-Crespo, V., et al. Basic numerical capacities and prevalence of developmental dyscalculia: The Havana survey. Developmental Psychology. 48 (1), 123-135 (2012).

- Hein, J., Bzufka, M. W., Neumärker, K. J. The specific disorder of arithmetic skills. Prevalence studies in a rural and an urban population sample and their clinico-neuropsychological validation. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 9, Suppl. 2 (2000).

- Geary, D. C., Nicholas, A., Li, Y., Sun, J. Developmental change in the influence of domain-general abilities and domain-specific knowledge on mathematics achievement: An eight-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology. 109 (5), 680-693 (2017).

- Cowan, R., Powell, D. The contributions of domain-general and numerical factors to third-grade arithmetic skills and mathematical learning disability. Journal of Educational Psychology. 106 (1), 214-229 (2014).

- Rubinsten, O., Henik, A. Developmental Dyscalculia: heterogeneity might not mean different mechanisms. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 13 (2), 92-99 (2009).

- Peake, C., Jiménez, J. E., Rodríguez, C. Data-driven heterogeneity in mathematical learning disabilities based on the triple code model. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 71, (2017).

- Chan, W. W. L., Wong, T. T. Y. Subtypes of mathematical difficulties and their stability. Journal of Educational Psychology. 112 (3), 649-666 (2020).

- Bartelet, D., Ansari, D., Vaessen, A., Blomert, L. Cognitive subtypes of mathematics learning difficulties in primary education. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 35 (3), 657-670 (2014).

- Geary, D. C., Hamson, C. O., Hoard, M. K. Numerical and arithmetical cognition: a longitudinal study of process and concept deficits in children with learning disability. Journal of experimental child psychology. 77 (3), 236-263 (2000).

- Landerl, K., Bevan, A., Butterworth, B. Developmental dyscalculia and basic numerical capacities: a study of 8-9-year-old students. Cognition. 93 (2), 99-125 (2004).

- Moura, R., et al. Journal of Experimental Child Transcoding abilities in typical and atypical mathematics achievers : The role of working memory and procedural and lexical competencies. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 116 (3), 707-727 (2013).

- De Smedt, B., Gilmore, C. K. Defective number module or impaired access? Numerical magnitude processing in first graders with mathematical difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 108 (2), 278-292 (2011).

- Andersson, U., Östergren, R. Number magnitude processing and basic cognitive functions in children with mathematical learning disabilities. Learning and Individual Differences. 22 (6), 701-714 (2012).

- Geary, D. C., Hoard, M. K., Nugent, L., Byrd-Craven, J. Development of Number Line Representations in Children With Mathematical Learning Disability. Developmental neuropsychology. , (2008).

- van't Noordende, J. E., van Hoogmoed, A. H., Schot, W. D., Kroesbergen, E. H. Number line estimation strategies in children with mathematical learning difficulties measured by eye tracking. Psychological Research. 80 (3), 368-378 (2016).

- Chan, B. M., Ho, C. S. The cognitive profile of Chinese children with mathematics difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 107 (3), 260-279 (2010).

- Geary, D. C., Hoard, M. K., Bailey, D. H. Fact Retrieval Deficits in Low Achieving Children and Children With Mathematical Learning Disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 45 (4), 291-307 (2012).

- Clarke, B., Shinn, M., Shinn, M. R. A Preliminary Investigation Into the Identification and Development of Early Mathematics Curriculum-Based Measurement. Psychology Review. 33 (2), 234-248 (2004).

- David, C. V. Working memory deficits in Math learning difficulties: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 58 (2), 67-84 (2012).

- Peng, P., Fuchs, D. A Meta-Analysis of Working Memory Deficits in Children With Learning Difficulties: Is There a Difference Between Verbal Domain and Numerical Domain. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 49 (1), 3-20 (2016).

- Peng, P., et al. Examining the mutual relations between language and mathematics: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 146 (7), 595-634 (2020).

- Andersson, U., Lyxell, B. Working memory deficit in children with mathematical difficulties: A general or specific deficit. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 96 (3), 197-228 (2007).

- Guzmán, B., Rodríguez, C., Sepúlveda, F., Ferreira, R. A. Number Sense Abilities , Working Memory and RAN: A Longitudinal. Revista de Psicodidáctica. 24, 62-70 (2019).

- Passolunghi, M. C., Cornoldi, C. Working memory failures in children with arithmetical difficulties. Child Neuropsychology. 14 (5), 387-400 (2008).

- vander Sluis, S., vander Leij, A., de Jong, P. F. Working Memory in Dutch Children with Reading- and Arithmetic-Related LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 38 (3), 207-221 (2005).

- Lefevre, J. A., et al. Pathways to Mathematics: Longitudinal Predictors of Performance. Child Development. 81 (6), 1753-1767 (2010).

- Simmons, F. R., Singleton, C. Do weak phonological representations impact on arithmetic development? A review of research into arithmetic and dyslexia. Dyslexia. 14 (2), 77-94 (2008).

- Kleemans, T., Segers, E., Verhoeven, L. Role of linguistic skills in fifth-grade mathematics. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 167, 404-413 (2018).

- Hecht, S. A., Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A. The relations between phonological processing abilities and emerging individual differences in mathematical computation skills: A longitudinal study from second to fifth grades. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 79 (2), 192-227 (2001).

- García-Vidal, J., González-Manjón, D., García-Ortiz, B., Jiménez-Fernández, A. Evamat: batería para la evaluación de la competencia matemática. , Madrid. (2010).

- Gregoire, J., Nöel, M. P., Van Nieuwenhoven, C. TEDI-MATH. , Spanish version by M. J. Sueiro & J. Perena (2005).

- Navarro, J. I., et al. Estimación del aprendizaje matemático mediante la versión española del Test de Evaluación Matemática Temprana de Utrecht. European Journal of Education and Psychology. 2 (2), 131 (2009).

- Cerda Etchepare, G., et al. Adaptación de la versión española del Test de Evaluación Matemática Temprana de Utrecht en Chile . Estudios pedagógicos. 38, Valdivia. 235-253 (2012).

- Van De Rijt, B. A. M., Van Luit, J. E. H., Pennings, A. H. The construction of the Utrecht early mathematical competence scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 59 (2), 289-309 (1999).

- Ginsburg, H., Baroody, A. Test of early math ability. , Madrid. Spanish adaptation by Nunez, M. & Lozano, I (2007).

- Butterworth, B. Dyscalculia Screener. , (2003).

- Beacham, N., Trott, C. Screening for Dyscalculia within HE. MSOR Connections. 5 (1), 1-4 (2005).

- Karagiannakis, G., Noël, M. -P. Mathematical Profile Test: A Preliminary Evaluation of an Online Assessment for Mathematics Skills of Children in Grades 1-6. Behavioral Sciences. 10 (8), 126 (2020).

- Lee, E. K., et al. Development of the Computerized Mathematics Test in Korean Children and Adolescents. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 28 (3), 174-182 (2017).

- Cangöz, B., Altun, A., Olkun, S., Kaçar, F. Computer based screening dyscalculia: Cognitive and neuropsychological correlates. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology. 12 (3), 33-38 (2013).

- Zygouris, N. C., et al. Screening for disorders of mathematics via a web application. IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON. , 502-507 (2017).

- Jiménez, J. E., Rodríguez, C. Batería multimedia para la evaluación de habilidades cognitivas y básicas en matemáticas (BM-PROMA). , Software (2020).

- Nuerk, H. -C., Weger, U., Willmes, K. On the Perceptual Generality of the Unit-DecadeCompatibility Effect. Experimental Psychology (formerly "Zeitschrift für Experimentelle Psychologie". 51 (1), 72-79 (2004).

- Nuerk, H. -C., Weger, U., Willmes, K. Decade breaks in the mental number line? Putting the tens and units back in different bins. Cognition. 82 (1), 25-33 (2001).

- Booth, J. L., Siegler, R. S. Developmental and individual differences in pure numerical estimation. Developmental Psychology. 42 (1), 189-201 (2006).

- Case, R., Kurland, D. M., Goldberg, J. Operational efficiency and the growth of short-term memory span. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 33 (3), 386-404 (1982).

- Denckla, M. B., Rudel, R. Rapid "Automatized" Naming of Pictured Objects, Colors, Letters and Numbers by Normal Children. Cortex. 10 (2), 186-202 (1974).

- Milner, B. Interhemispheric differences in the localization of psychological processes in man. British Medical Bulletin. 27, 272-277 (1971).

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 48 (2), 1-36 (2012).

- Knops, A., Nuerk, H. -C., Göbel, S. M. Domain-general factors influencing numerical and arithmetic processing. Journal of Numerical Cognition. 3 (2), 112-132 (2017).

- Torresi, S. Review Interaction between domain-specific and domain-general abilities in math's competence. Journal of Applied Cognitive Neuroscience. 1 (1), 43-51 (2020).

- Arsalidou, M., Pawliw-Levac, M., Sadeghi, M., Pascual-Leone, J. Brain areas associated with numbers and calculations in children: Meta-analyses of fMRI studies. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 30, 239-250 (2018).

- Dehaene, S. Varieties of numerical abilities. Cognition. 44 (1-2), 1-42 (1992).

- Streiner, D. L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Statistical Developments and Applications. 80 (1), 99-103 (2003).

- Zainudin, A. Validating the measurement model CFA. A handbook on structural equation modeling. , 54-73 (2014).

- Brown, T. A. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied reaearch. (9), The Gildford Press. New York, NY. (2015).

- Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. , The Gildford Press. New York, NY. (2011).

- Putnick, D. L., Bornstein, M. H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review. 41, 71-90 (2016).

- Artiles, C., Jiménez, J. E. Prueba de Cáculo Artimético. Normativización de instrumentos para la detección e identificación de las necesidades educativas del alumnado con trastorno por déficit de atención con o sin hiperactividad (TDAH) o alumnado con dificultades específicas de aprendizaje (DEA). , 13-26 (2011).

- Hosmer, D., Lemeshow, S., Rod, X. Sturdivant. Applied Logistic Regression. , Hoboken. (2013).

- Smolkowski, K., Cummings, K. D. Evaluation of Diagnostic Systems: The Selection of Students at Risk of Academic Difficulties. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 41 (1), 41-54 (2015).

- Piazza, M., et al. Developmental trajectory of number acuity reveals a severe impairment in developmental dyscalculia. Cognition. 116 (1), 33-41 (2010).

- Van Hoof, J., Verschaffel, L., Ghesquière, P., Van Dooren, W. The natural number bias and its role in rational number understanding in children with dyscalculia. Delay or deficit. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 71, 181-190 (2017).

- Swanson, H. L., Jerman, O., Zheng, X. Growth in Working Memory and Mathematical Problem Solving in Children at Risk and Not at Risk for Serious Math Difficulties. Journal of Educational Psychology. 100 (2), 343-379 (2008).

- Kroesbergen, E., Van Luit, J. E. H., Van De Rijt, B. A. M. Young children at risk for math disabilities: Counting skills and executive functions. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. , (2009).