Criando uma coluna de Winogradsky: um método para enriquecer as espécies microbianas em uma amostra de sedimento

English

Share

Overview

Fonte: Elizabeth Suter1, Christopher Corbo1, Jonathan Blaize1

1 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Wagner College, 1 Campus Road, Staten Island NY, 10301

A coluna Winogradsky é um ecossistema em miniatura e fechado usado para enriquecer comunidades microbianas de sedimentos, especialmente aquelas envolvidas no ciclismo de enxofre. A coluna foi usada pela primeira vez por Sergei Winogradsky na década de 1880 e desde então tem sido aplicada no estudo de muitos microrganismos diversos envolvidos na biogeoquímica, como fotossintingesizers, oxidantes de enxofre, redutores de sulfato, methanogens, oxidantes de ferro, ciclodificadores de nitrogênio e muito mais (1,2).

A maioria dos microrganismos na Terra são considerados inculturais,o que significa que eles não podem ser isolados em um tubo de ensaio ou em uma placa de petri (3). Isso se deve a muitos fatores, incluindo que os microrganismos dependem de outros para certos produtos metabólicos. As condições em uma coluna de Winogradsky imitam de perto o habitat natural de um microrganismo, incluindo suas interações com outros organismos, e permitem que eles sejam cultivados em laboratório. Por isso, essa técnica permite que os cientistas estudem esses organismos e entendam como eles são importantes para os ciclos biogeoquímicos da Terra sem ter que cultivá-los isoladamente.

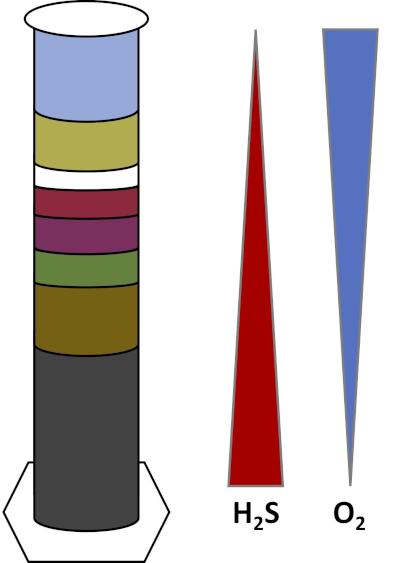

Os ambientes da Terra estão cheios de microrganismos que prosperam em todos os tipos de habitats,como solos, água oceânica, nuvens e sedimentos em alto mar. Em todos os habitats, os microrganismos dependem uns dos outros. À medida que um microrganismo cresce, ele consome substratos particulares, incluindo combustíveis ricos em carbono, como açúcares, bem como nutrientes, vitaminas e gases respiratórios como oxigênio. Quando esses recursos importantes se esgotam, diferentes microrganismos com diferentes necessidades metabólicas podem então florescer e prosperar. Por exemplo, na coluna Winogradsky, os micróbios primeiro consomem o material orgânico adicionado enquanto esgotam o oxigênio nas camadas inferiores da coluna. Uma vez que o oxigênio é usado, organismos anaeróbicos podem então assumir e consumir diferentes materiais orgânicos. Esse desenvolvimento consecutivo de diferentes comunidades microbianas ao longo do tempo é chamado de sucessão (4). A sucessão microbiana é importante em uma coluna winogradsky, onde a atividade microbiana altera a química do sedimento, que então afeta a atividade de outros micróbios e assim por diante. Muitos microrganismos em solos e sedimentos também vivem ao longo de gradientes,que são zonas transitórias entre dois tipos diferentes de habitats baseados nas concentrações de substratos (5). No ponto correto no gradiente, um micróbio pode receber quantidades ideais de diferentes substratos. À medida que uma coluna winogradsky se desenvolve, ela começa a imitar esses gradientes naturais, particularmente em oxigênio e sulfeto (Fig. 1).

Figura 1: Uma representação dos gradientes de oxigênio (O2) e sulfeto (H2S) que se desenvolvem em uma coluna winogradsky.

Em uma coluna winogradsky, lama e água de um lago ou pântano são misturados em uma coluna transparente e permitidos a incubação, tipicamente à luz. Substratos adicionais são adicionados à coluna para dar à comunidade fontes de carbono, geralmente sob a forma de celulose, e enxofre. Fotossintificadores normalmente começam a crescer nas camadas superiores do sedimento. Esses microrganismos fotossintéticos são em grande parte compostos por cianobactérias,que produzem oxigênio e aparecem como uma camada verde ou marrom-vermelha (Fig. 2, Tabela 1). Enquanto a fotossíntese produz oxigênio, o oxigênio não é muito solúvel em água e diminui abaixo dessa camada (Fig. 1). Isso cria um gradiente de oxigênio, variando de altas concentrações de oxigênio nas camadas superiores a zero oxigênio nas camadas inferiores. A camada oxigenada é chamada de camada aeróbica e a camada sem oxigênio é chamada de camada anaeróbica.

Na camada anaeróbica, muitas comunidades microbianas diferentes podem proliferar dependendo do tipo e quantidade de substratos disponíveis, da fonte dos micróbios iniciais e da porosidade do sedimento. No fundo da coluna, organismos que aeróbios quebram matéria orgânica podem prosperar. A fermentação microbiana produz ácidos orgânicos a partir da quebra da celulose. Esses ácidos orgânicos podem então ser usados por redutores de sulfato,que oxidam esses orgânicos usando sulfato, e produzem sulfeto como subproduto. A atividade dos redutores de sulfato é indicada se o sedimento ficar preto, pois o ferro e o sulfeto reagem para formar minerais pretos de ferro-sulfeto (Fig. 2, Tabela 1). O sulfeto também difunde para cima, criando outro gradiente no qual as concentrações de sulfeto são altas na parte inferior da coluna e baixas na parte superior da coluna (Fig. 1).

Perto do meio da coluna, os oxidantes de enxofre aproveitam o fornecimento de oxigênio de cima e sulfeto de baixo. Com a quantidade certa de luz, oxidantes de enxofre fotossintéticos podem se desenvolver nessas camadas. Esses organismos são conhecidos como bactérias de enxofre verde e roxo , e muitas vezes aparecem como filamentos e manchas verde, roxo ou roxo-vermelho (Fig. 2, Tabela 1). As bactérias de enxofre verde têm maior tolerância ao sulfeto e geralmente se desenvolvem na camada diretamente abaixo das bactérias do enxofre roxo. Acima das bactérias de enxofre roxo, bactérias não-enxofre roxas também podem se desenvolver. Esses organismos fotossintestêm usando ácidos orgânicos como doadores de elétrons em vez de sulfeto e muitas vezes aparecem como uma camada vermelha, roxa, laranja ou marrom. Oxidantes de enxofre não fotosintéticos podem desenvolver-se acima das bactérias não-enxofre roxas, e estes geralmente aparecem como filamentos brancos (Fig. 2, Tabela 1). Além disso, bolhas também podem se formar na coluna Winogradsky. Bolhas nas camadas aeróbicas indicam a produção de oxigênio pelas cianobactérias. Bolhas nas camadas anaeróbicas são provavelmente devido à atividade de metanogens, organismos que aeróbicamente quebram matéria orgânica e formam metano como subproduto.

| Posição na Coluna | Grupo funcional | Exemplos de organismos | Indicador Visual |

| Início | Fotossintificadores | Cianobactérias | Camada verde ou marrom-avermelhada. Às vezes bolhas de oxigênio. |

| Oxidantes de enxofre não fotosintéticos | Beggiatoa | Camada branca. | |

| Bactérias não-enxofre roxas | Rhodomicrobium, Rhodospirilum, Rhodopseuodmonas | Camada vermelha, roxa, laranja ou marrom. | |

| Bactérias de enxofre roxo | Chromatium | Camada roxa ou roxa-vermelha. | |

| Bactérias de enxofre verde | Clorobio | Camada verde. | |

| Bactérias redutoras de sulfato | Desulfovibrio, Desulfotomaculum, Desulfobacter, Desulfuromonas | Camada preta. | |

| Fundo | Methanogênios | Metanoococcus | Às vezes bolhas de metano. |

Tabela 1: Os principais grupos de bactérias que podem aparecer em uma coluna clássica de Winogradsky, de cima a baixo. Exemplos de organismos de cada grupo são dados, e os indicadores visuais de cada camada de organismos são listados. Baseado em Perry et al. (2002) e Rogan et al. (2005).

Procedure

Results

In this experiment, water and sediment were collected from a freshwater habitat. Two Winogradsky columns were constructed and allowed to develop: a classical Winogradsky column incubated in the light at room temperature (Fig. 2A) and a Winogradsky column incubated in the dark at room temperature (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2B: A photo of classical Winogradsky column (left), incubated at room temperature in light for 68 days and a Winogradsky column incubated at room temperature in the dark for 68 days (right).

After allowing the columns to develop for 7-9 weeks, the layers in the classical column can be compared to the column incubated in the dark (Fig. 2B). In the classical Winogradsky column, a green cyanobacterial layer can be observed near the top of the tube. Near the center of the tube, a red-purple layer can be observed, indicative of purple nonsulfur bacteria. Under this layer, a purple-red layer is observed, indicative of purple sulfur bacteria. Directly under this layer, black sediment can be observed in the anaerobic region of the column, indicative of sulfate reducing bacteria.

The column grown in the dark (Fig. 2B) developed differently than the classical Winogradsky column. Like the classical column, the dark column yielded black sediment near the bottom of the column, indicative of sulfate reducing bacteria. The dark column did not yield the green cyanobacterial layer, nor the red, purple, or green layers indicative of purple nonsulfur, purple sulfur, and green sulfur bacteria, respectively. These groups are dependent on light for growth, and therefore unable to grow in the dark.

The precise results of each Winogradsky column will vary widely with their incubation conditions and their source habitats.

Microbial communities originating from freshwater habitats will not be accustomed to high salt concentrations and the addition of salt may slow down or inhibit growth. Conversely, there may be sufficient halophilic bacteria in brackish and saltwater habitats so that the addition of salts makes no difference or even enhances the growth of particular layers when compared to a column without added salts.

Sandy sediments are more porous than muddy sediments. If enough sulfide is produced in such porous sediments, sulfides can diffuse all the way to the top of the column and inhibit growth of aerobic organisms. In this case, the column may only contain layers indicative of anaerobes and may not contain any aerobes, such as the cyanobacteria.

Freshwater generally contains less sulfate than saltwater. Sulfate is important for the growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Sulfate reducers create sulfide as a byproduct and are indicated by the development of a black layer in the bottom of the column. If sulfate is not supplemented to freshwater communities, sulfate reducers may not produce enough sulfide. The creation of the sulfide byproduct is important for the growth of green and purple sulfur bacteria and the nonphotosynthetic sulfur oxidizers. In these cases, sulfur oxidizers can still grow using the egg yolk as a source of sulfur, even if the sulfate reducers (black layer) never develop.

Different wavelengths of light should select for organisms with different absorption pigments. A column kept in the dark will only allow for nonphotosynthetic organisms to grow, including sulfate reducers, iron oxidizers, and methanogens. Photosynthesizers have pigments that absorb light at different wavelengths within the visible range (~400-700nm). By covering a column with, for example, blue cellophane, blue light (~450-490nm) is blocked from entering the column. All of the photosynthesizers in the column have pigments which require the blue wavelengths (6) and their growth should be inhibited. On the other hand, red cellophane will block light of ~635-700nm. These wavelengths are important for the pigments used by cyanobacteria (6), while purple sulfur, green sulfur, and purple nonsulfur bacteria may still be able to grow.

Different microbial communities may have vastly different adaptive abilities to cope with changes in temperatures. High temperatures can enhance rates of microbial activity when sufficient thermophiles are present. On the other hand, in the absence of thermophiles, high temperatures may decrease overall microbial activity. Similarly, low temperatures may decrease overall microbial activity unless the microbial community contains sufficient psychrophiles.

Applications and Summary

The Winogradsky column is an example of an interdependent microbial ecosystem. After mixing mud, water, and additional carbon and sulfur substrates in a vertical column, the stratified ecosystem should stabilize into separate, stable zones over several weeks. These zones are occupied by different microorganisms which flourish at a particular spot along the gradient between the sulfide-rich sediment in the bottom and the oxygen-rich sediment at the top. By manipulating the conditions and substrates within the Winogradsky column, the presence and activity of different microorganisms such as halophiles, thermophiles, psychrophiles, sulfur oxidizers, sulfur reducers, iron oxidizers, and photosynthesizers can be observed.

References

- Zavarzin G. (2006). Winogradsky and modern microbiology. Microbiology 75(6): 501-511. doi: 10.1134/s0026261706050018

- Esteban DJ, Hysa B, and Bartow-McKenney C (2015). Temporal and Spatial Distribution of the Microbial Community of Winogradsky Columns. PLoS ONE 10(8): e0134588. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134588

- Lloyd KG, Steen AD, Ladau J, Yin J, and Crosby L. (2018). Phylogenetically novel uncultured microbial cells dominate Earth microbiomes. mSystems 3(5): e00055-18. doi:10.1128/mSystems.00055-18

- Anderson DC, and Hairston RV (1999). The Winogradsky Column & Biofilms: Models for Teaching Nutrient Cycling & Succession in an Ecosystem. The American Biology Teacher, 61(6): 453-459. doi: 10.2307/4450728

- Dang H, Klotz MG, Lovell CR and Sievert SM (2019) Editorial: The Responses of Marine Microorganisms, Communities and Ecofunctions to Environmental Gradients. Frontiers in Microbiology 10(115). doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00115

- Stomp M, Huisman J, Stal LJ, and Matthijs HCP. (2007) Colorful niches of phototrophic microorganisms shaped by vibrations of the water molecule. ISME Journal. 1(4): 271-282. doi:10.1038/ismej.2007.59

- Perry JJ, Staley JT, and Lory S. (2002) Microbial Life, First Edition, published by Sinauer Associates

- Rogan B, Lemke M, Levandowsky M, and Gorrel T. (2005) Exploring the Sulfur Nutrient Cycle Using the Winogradsky Column. The American Biology Teacher, 67(6): 348-356. doi: 10.2307/4451860

Transcript

Most of the Earth’s microorganisms cannot be cultured in a lab, often because they rely on other microbes within their native communities. A Winogradsky column, named for its inventor Sergei Winogradsky, is a miniature, enclosed ecosystem which enriches the microbial communities within a sediment sample, enabling scientists to study many of the microbes that play a vital role in Earth’s biogeochemical processes, without needing to isolate and culture them individually.

Typically, mud and water from an ecosystem, such as a pond or a marsh, are mixed. As an optional experiment, salt can be added to this mixture to enrich various halophile species. Next, a small portion of the mixture is supplemented with carbon, usually in the form of cellulose from newspaper, and sulfur, usually from an egg yolk. For another optional experiment, a nail can be added to this mixture to enrich certain Gallionella species. This new mixture is then added to a transparent column, so that the column is one quarter full. Finally, the rest of the mud mixture and more water is added to the column until it is most of the way full.

Succession, which refers to the consecutive development of different microbial communities over time, can be observed in real time with a Winogradsky column. As microbes grow within the column, they consume specific substrates and change the chemistry of their environment. When their substrates are depleted, the original microbes die off and microbes with different metabolic needs can flourish in the altered environment. Over time, visibly distinct layers begin to form, each containing parts of a bacterial community with different microenvironmental needs.

For example, photosynthetic microbes, largely composed of cyanobacteria, form green or red-brown layers near the top of the column. Since photosynthesis produces oxygen, often seen as bubbles in the top portion of the column, a gradient is formed with the highest oxygen concentrations near the top, and the lowest towards the bottom. Depending upon the available substrates, different microbial communities can grow in the anaerobic bottom layer. Bubbles in this layer can indicate the presence of methanogens, which create methane gas via fermentation. Here, the microbial fermentation of cellulose results in organic acids. Sulfate reducers oxidize those acids to produce sulfide, and their activity is indicated by black sediment. Sulfide diffuses upward in the column, creating yet another gradient where sulfide concentrations are highest towards the bottom of the column, and lowest near the top. Towards the middle of the column, sulfur oxidizers utilize the oxygen from above and sulfide from below. With adequate light, photosynthetic sulfur oxidizers, such as green and purple sulfur bacteria, develop. Green sulfur bacteria tolerate higher sulfide concentrations. Thus, they grow directly below the purple sulfur bacteria. Directly above this layer, purple non-sulfur bacteria form a red-orange layer. Nonphotosynthetic sulfur oxidizers are indicated by the presence of white filaments.

Conditions such as light and temperature can also be varied to enrich other communities. In this video, you will learn how to construct a Winogradsky column, and vary the growing conditions and substrates to enrich specific microbial communities.

First, locate an appropriate aquatic ecosystem, such as a pond or marsh. The sediment samples should come from the area near the water’s edge, and be completely saturated with water. Then, use a shovel and a bucket to collect one to two liters of the saturated mud. Next, obtain approximately three liters of fresh water from the same source and return to the lab with the field samples.

In the lab, put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Now, transfer approximately 750 milliliters of mud to a mixing bowl. Then, sift through the mud to remove large rocks, twigs, or leaves and use a spoon to break apart any clumps. Next, add some of the fresh water to the mixing bowl, and stir with a large spoon. Add water until the consistency of the water-mud mixture is similar to a milkshake. Continue to make sure there are no clumps.

As an optional experiment, select for halophilic bacteria by adding 25 to 50 milligrams of salt to the mud mixture.

Then, transfer approximately 1/3 of the water-mud mixture to a second mixing bowl. Add one egg yolk and a handful of shredded newspaper to the bowl. Next, add this mixture to the column, until it is about 1/4 full. Next, add the water-mud mixture without the egg and newspaper to the column, until it is approximately 3/4 full. Then, add more water to the column, leaving a 1/2 inch space on top. Cover the column with plastic wrap and secure it with a rubber band.

Incubate the column in the light near a window at room temperature for the next four to eight weeks. Throughout the incubation period, monitor changes in the Winogradsky column at least once a week for the development of different colored layers and the formation of bubbles. Additionally, record the time it takes for different layers to develop.

Another modification that can be done is incubating the column near a radiator to select for thermophilic bacteria, or in a refrigerator to select for psychrophilic bacteria. Vary the light conditions by placing different columns in high light, low light, or darkness to incubate. Alternatively, limit the wavelength of incoming light by covering the column with different shades of cellophane to determine which colors select for different bacterial groups. For another optional experiment, to enrich iron-oxidizing bacteria, add a nail to the mud-water mixture prior to the addition of newspaper and an egg yolk.

After one to two weeks, growth of the cyanobacterial layer is indicated by a green or red-brown film on top of the mud layer of the classical Winogradsky column. Over time, the appearance and evolution of the different layers is monitored, each indicative of the different types of bacteria present. When comparing a column grown in the dark to a traditional Winogradsky column, we see the dark treatment yields the black layer at the bottom of the column, indicative of sulfate-reducing bacteria.

The dark column may also yield other layers, depending on other incubation conditions. Additionally, the dark column doesn’t yield the green cyanobacterial layer, nor the red, purple, or green layers indicative of purple non-sulfur, purple sulfur, and green sulfur bacteria respectively. These groups are dependent on light for growth.