18.2:

起電力

18.2:

起電力

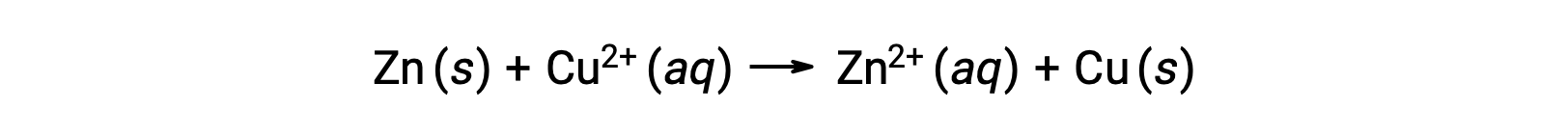

電気は、電子やイオンが溶液や導電性媒体を流れることで生じます。この電子の流れ、具体的には電荷の流れを「電流」と定義します。電線の中を電子が移動すると、電流が発生します。酸化還元反応では、反応の過程で電子の授受を伴う。亜鉛と銅の自発的な酸化還元反応では、亜鉛を銅イオン溶液に浸すと、片方からもう一方への電子移動が起こります。

電子を失いやすい亜鉛は酸化されて亜鉛イオンとなり、銅イオンは還元されて固体の銅となります。ただし、この反応では電気は発生しません。.

電流と電子の流れ方

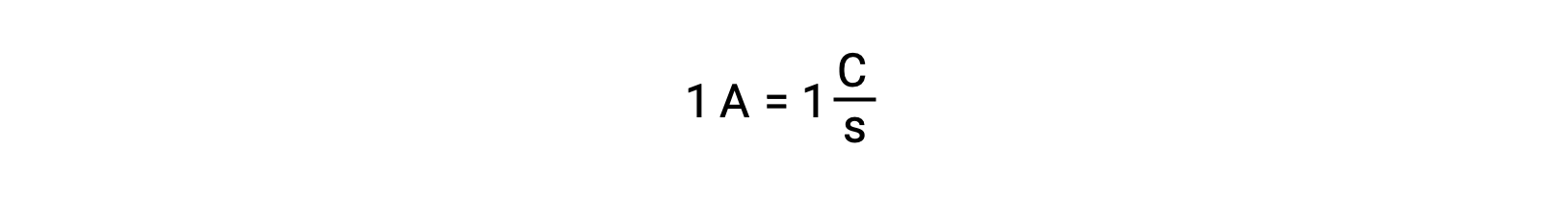

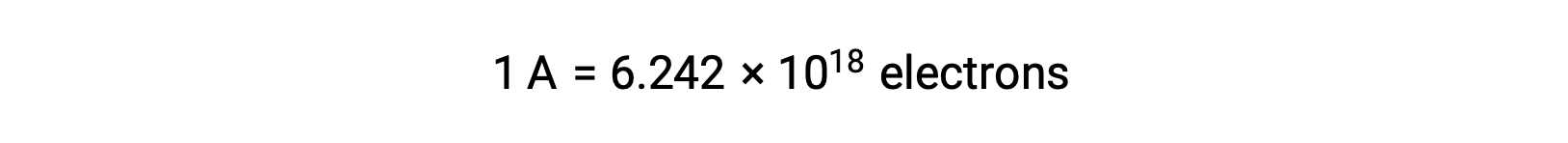

溶液中では、還元剤から酸化剤へと直接電子が移動します。片方の反応物が物理的に別の容器へと隔離され、電線などの外部導体を介して接続された場合も、反応物による電子の放出や受容の傾向は変わりません。ここで異なるのは、2つの半反応をつなぐ導線の中を電子が流れるという点です。この電子の流れが電流となり、電球などの電子機器を動かしています。電流の単位はアンペアです。1アンペアは、1秒間に1 クーロンの電荷が流れることに相当し、1秒間に6.24×10−18個の電子が流れることに相当します。

電子は1.602 × 10−19 Cの電荷を持っているため、1アンペアは1秒間に6.242 × 1018 個の電子が流れることに相当します。

電流・電位差・起電力の駆動力

電流の流れは、滝を下る水の流れに似ています。水の流れは重力の位置エネルギーの差によって駆動されるが、電子の流れは反応物間の電気的なポテンシャル差によって駆動されます。この電位の差は、電位差、起電力、電池電位のいずれかの用語で表現されます。起電力は、2つの反応体間の駆動力と電子移動の方向を示す指標です。

酸化還元反応には、自発的に起こるものとそうでないものがあります。例えば、銅線は銀(I)イオンによって自発的に酸化されるが、鉛(II)イオンの溶液に浸しても何の反応も起こりません。これは、Ag+ (aq)とPb2+ (aq)という2つの化学種の銅に対する酸化還元活性の違いによるもので、銀イオンは銅を自発的に酸化しますが、鉛イオンは酸化しません。このような電気化学における酸化還元反応性の違いは、「電極電位」(一般的には「電圧」とも呼ばれる)という言葉で定量化することができます。

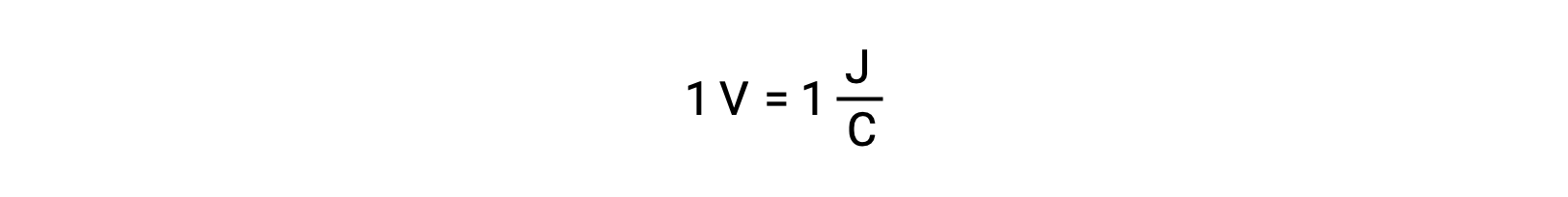

孤立した2つの反応物の電極電位は、電圧計で測定され、電池の電圧として読み取られます。1ボルトは、1クーロンの電荷あたり1ジュールのエネルギーに相当します。

電極電位が高いほど起電力が大きく、電子の移動が容易であることを示します。このような起電力(電極電位)は、反応物の性質、反応温度、反応に含まれるイオンの濃度などによって変化します。

上記の文章は以下から引用しました。 OpenStax, Chemistry 2e, Section 17.3: Electrode and Cell Potentials.