12.10:

צניחת נקודת קיפאון ועליית נקודת רתיחה

12.10:

צניחת נקודת קיפאון ועליית נקודת רתיחה

Boiling Point Elevation

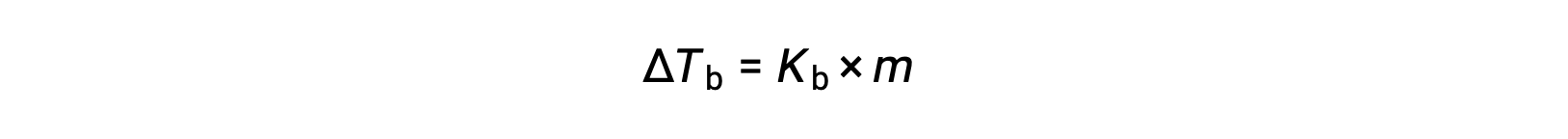

The boiling point of a liquid is the temperature at which its vapor pressure is equal to ambient atmospheric pressure. Since the vapor pressure of a solution is lowered due to the presence of nonvolatile solutes, it stands to reason that the solution’s boiling point will subsequently be increased. Vapor pressure increases with temperature, and so a solution will require a higher temperature than will pure solvent to achieve any given vapor pressure, including one equivalent to that of the surrounding atmosphere. The increase in boiling point observed when a non-volatile solute is dissolved in a solvent, ΔTb, is called boiling point elevation and is directly proportional to the molal concentration of solute species:

where Kb is the boiling point elevation constant, or the ebullioscopic constant and m is the molal concentration (molality) of all solute species. Boiling point elevation constants are characteristic properties that depend on the identity of the solvent.

Freezing Point Depression

Solutions freeze at lower temperatures than pure liquids. This phenomenon is exploited in “de-icing” schemes that use salt, calcium chloride, or urea to melt ice on roads and sidewalks, and in the use of ethylene glycol as an “antifreeze” in automobile radiators. Seawater freezes at a lower temperature than freshwater, and so the Arctic and Antarctic oceans remain unfrozen even at temperatures below 0 °C (as do the body fluids of fish and other cold-blooded sea animals that live in these oceans).

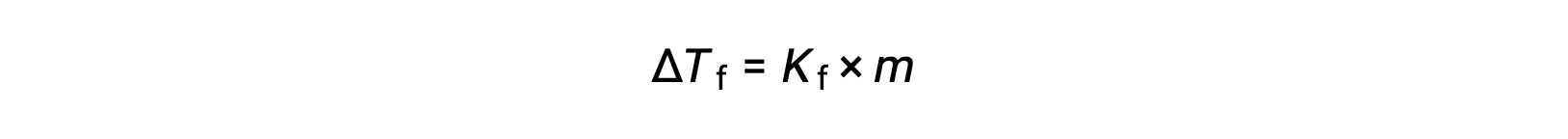

The decrease in freezing point of a dilute solution compared to that of the pure solvent, ΔTf, is called the freezing point depression and is directly proportional to the molal concentration of the solute

where m is the molal concentration of the solute and Kf is called the freezing point depression constant (or cryoscopic constant). Just as for boiling point elevation constants, these are characteristic properties whose values depend on the chemical identity of the solvent.

Determination of Molar Masses

Osmotic pressure and changes in freezing point, boiling point, and vapor pressure are directly proportional to the number of solute species present in a given amount of solution. Consequently, measuring one of these properties for a solution prepared using a known mass of solute permits determination of the solute’s molar mass.

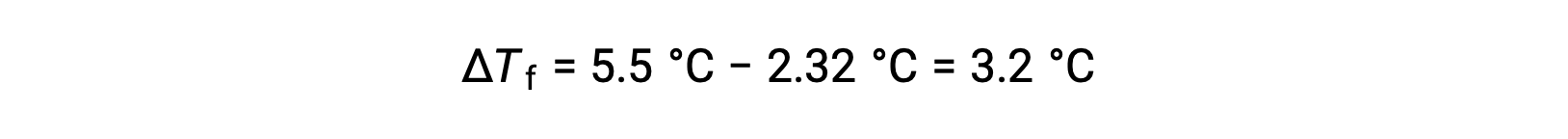

For example, a solution of 4.00 g of a nonelectrolyte dissolved in 55.0 g of benzene is found to freeze at 2.32 °C. Assuming ideal solution behavior, what is the molar mass of this compound?

To solve this problem, first, the change in freezing point from the observed freezing point and the freezing point of pure benzene is calculated:

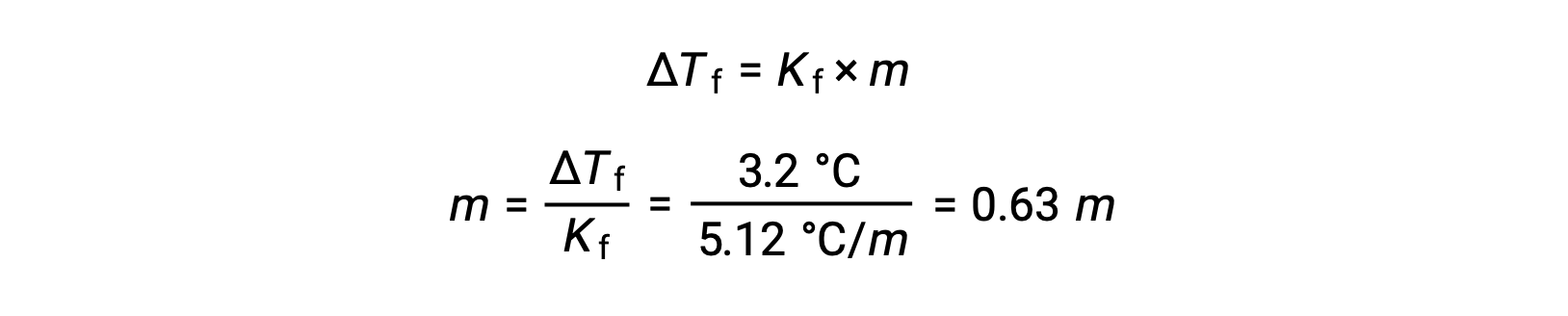

Then, the molal concentration is determined from Kf, the freezing point depression constant for benzene, and ΔTf:

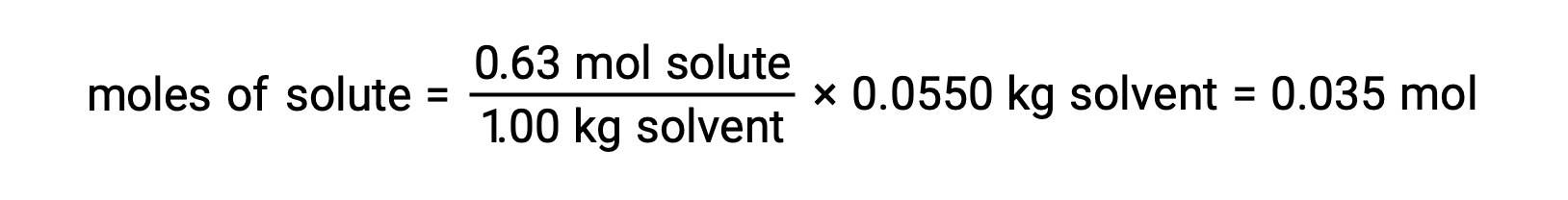

Next, the number of moles of the compound in the solution is found from the molal concentration and the mass of solvent that was used to make the solution.

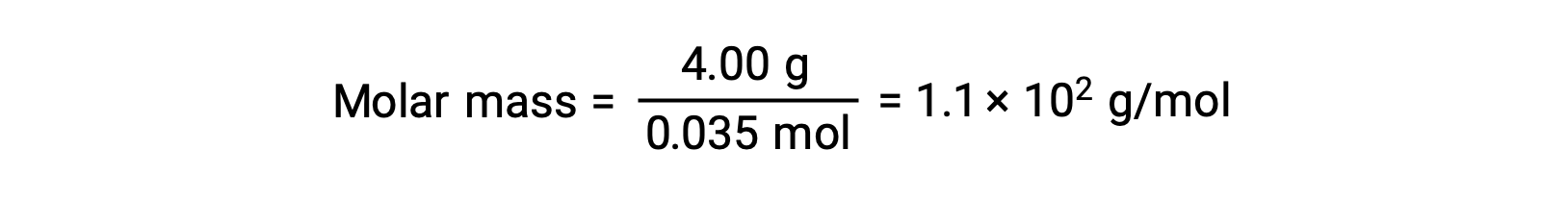

And, finally, the molar mass from the mass of the solute and the number of moles in that mass is determined.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Section 11.4: Colligative Properties.

Suggested Reading

- Steffel, Margaret J. "Raoult's law: A general chemistry experiment." Journal of Chemical Education 60, no. 6 (1983): 500.

- Berka, Ladislav H., and Nicholas Kildahl. "Experiments for Modern Introductory Chemistry: Intermolecular Forces and Raoult's Law." Journal of chemical education 71, no. 7 (1994): 613.