Esame obiettivo dei linfonodi

English

Share

Overview

Fonte: Richard Glickman-Simon, MD, Assistant Professor, Dipartimento di Sanità Pubblica e Medicina di Comunità, Tufts University School of Medicine, MA

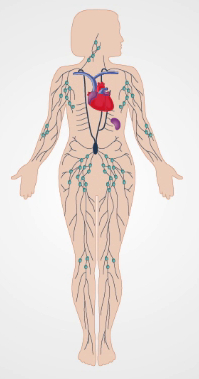

Il sistema linfatico ha due funzioni principali: restituire il fluido extracellulare alla circolazione venosa ed esporre sostanze antigeniche al sistema immunitario. Mentre il fluido raccolto passa attraverso i canali linfatici sulla via del ritorno alla circolazione sistemica, incontra più nodi costituiti da gruppi altamente concentrati di linfociti. La maggior parte dei canali e dei nodi linfatici risiedono in profondità all’interno del corpo e, pertanto, non sono accessibili all’esame fisico (Figura 1). Solo i nodi vicino alla superficie possono essere ispezionati o palpati. I linfonodi sono normalmente invisibili e anche i nodi più piccoli non sono palpabili. Tuttavia, i nodi più grandi (>1 cm) nel collo, nelle ascelle e nelle aree inguinali sono spesso rilevabili come masse morbide, lisce, mobili, non tenere, a forma di fagiolo incastonate nel tessuto sottocutaneo.

La linfoadenopatia di solito indica un’infezione o, meno comunemente, un cancro nell’area del drenaggio linfatico. I nodi possono diventare ingranditi, fissi, fermi e/o teneri a seconda della patologia presente. Ad esempio, un linfonodo morbido e tenero palpabile vicino all’angolo della mandibola può indicare una tonsilla infetta, mentre un linfonodo fermo, ingrandito, non tenero palpabile nell’ascella di una paziente di sesso femminile può essere un segno di cancro al seno.

I linfonodi regionali che drenano l’area di un’infezione localizzata in genere rimangono invisibili, ma possono diventare ingranditi e teneri alla palpazione. Una ferita infetta o cellulite può anche causare linfangite o linfoadenite, una condizione in cui l’infezione si diffonde lungo la catena di canali linfatici e nodi. Questo può essere accompagnato dalla comparsa di strisce rosse e sintomi sistemici come febbre, brividi e malessere. In rari casi, l’intensità della reazione infiammatoria può far sì che i nodi aderiscano ai tessuti molli circostanti, fissandoli in posizione.

Molti tumori metastatici si diffondono prima ai linfonodi regionali. A differenza delle infezioni, le cellule maligne che invadono i linfonodi possono farli sentire irregolari e sodi (anche duri come la roccia) ma rimangono non teneri. Se il cancro invade le capsule esterne, i nodi possono diventare fissati ai tessuti molli circostanti o arruffati insieme. Il linfoma, un tumore primario intrinseco al sistema linfatico, può essere presente in qualsiasi parte del corpo come linfonodi ingrossati singoli o multipli, che possono diventare abbastanza grandi da vedere all’ispezione, e sono generalmente duri e non teneri alla palpazione. Oltre al linfoma, la linfoadenopatia diffusa può essere un’indicazione di disturbi infettivi o infiammatori generalizzati come l’HIV, la mononucleosi o la sarcoidosi.

Figura 1. Il sistema linfatico.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Most lymph nodes lie too deep to be accessible via physical examination. The superficial nodes are most efficiently assessed during regional examinations of the head and neck, breasts and axillae, upper extremities, lower extremities, and/or external genitalia. Because lymph nodes are constantly interacting with extracellular fluid draining from nearby tissues, their examination can provide information about the presence and status of infections or malignancies in the area. Nodes draining the site of a soft tissue infection are apt to become enlarged and tender but generally remain soft, smooth, and mobile. Hard, non-tender, matted, or fixed nodes are more typical of a spreading malignancy. Diffuse lymphadenopathy may indicate systemic diseases such as lymphomas, HIV, mononucleosis, or sarcoidosis. Finding a single abnormal node should prompt an examination of all nodes.

Transcript

The lymph node examination forms an essential part of the evaluation for infectious diseases and cancer. The lymphatic system is comprised of organs including the spleen, lymphatic channels and lymph nodes. The channels are responsible for returning the lymph formed from extracellular fluid back to the venous circulation.

On its way, the lymph encounters multiple lymph nodes. These nodes consist of highly concentrated clusters of lymphocytes, which play a critical role in maintaining immunity. Most lymph channels and nodes reside deep within the body and are too small to be assessed by physical examination. However, superficial, larger nodes, close to or more than one centimeter in diameter-primarily located in the head and neck region, the axillae and the inguinal areas-can be palpated and assessed.

Lymph nodes in these areas normally present as soft, smooth, movable, non-tender, bean-shaped structures imbedded in the subcutaneous tissue. However, sometimes nodes may become enlarged, fixed, firm, and/or tender depending on the pathology present. This condition is referred to as lymphadenopathy and it usually indicates an infection or, less commonly, a cancer in the area of lymph drainage. This video will review the anatomical location of the key lymph nodes as well as demonstrate the procedural steps of this examination.

Let’s begin by briefly reviewing the lymph nodes in the head and neck area. The list of palpable nodes in this region is extensive including the preauricular and posterior auricular nodes located in front and behind the ear, respectively, the mastoid node positioned superficial to the mastoid process and the occipital nodes found at the base of the skull. Around the mandible are the tonsillar nodes, the submandibular nodes, and the submental nodes. Another group of nodes surround the sternomastoid muscle. These include the superficial and deep cervical nodes. The last groups of nodes are the clavicular nodes, including the supra- and the infra-clavicular nodes. The infraclavicular nodes are also known as the apical nodes.

Upon entering the examination room, introduce yourself and briefly explain the maneuvers you’re going to conduct. Before beginning with the examination, sanitize your hands by using topical disinfectant solution. Start by asking the patient to flex their neck slightly forward and inspect for noticeably enlarged nodes. Following inspection, palpate the preauricular node located in front of the ear. Throughout the exam, palpate using the pads of your index and middle fingers to note the size, shape, number, pliability, texture, mobility, and tenderness of nodes bilaterally.

Next, move to the posterior auricular node located behind the ear followed by the mastoid node located superficial to the mastoid process, and the occipital nodes found posteriorly at the base of the skull. Then move onto the tonsillar nodes located at the angle of mandible, the submandibular nodes that lie midway between the angle and tip of the mandible, and the submental nodes located a few centimeters from the tip. Next, palpate the superficial cervical nodes situated beneath and anterior to the sternomastoid muscles. The deep cervical nodes are rarely palpable. This is followed by palpation of the posterior cervical nodes located between the anterior edge of the trapezius and posterior edge of the sternomastoid muscles. Finally, palpate the supraclavicular nodes found deep within the angle formed by the sternomastoid muscle and clavicle, and the infraclavicular, or the apical nodes, located on the underside of the clavicle.

Following palpation of the head and neck nodes, move to the axillae and upper extremities. The three groups of axillary nodes-lateral, subscapular, and pectoral-drain their lymph into the central axillary nodes that lay deep within the axillae. The central nodes, in turn, drain lymph into the apical and supraclavicular nodes. Of the four axillary groups, only the central nodes are usually palpable. Since most breast cancers drain here, the axillary and clavicular lymphatics need to be examined more carefully in women. Most parts of the upper extremities drain more or less directly into the axillary lymph nodes. One exception is drainage from the ulnar aspects of the hand and forearm, which first encounters the epitrochlear nodes above the elbow.

To examine the left axillary nodes, position yourself in front and to the left of the seated patient. Gently grasp the patient’s left wrist or elbow and slightly abduct the arm. Inform the patient that the following maneuver may feel slightly uncomfortable. Move your right hand high up into the left axilla, just behind the pectoralis muscle. With your fingers pointing toward the mid-clavicle, press them against the patient’s chest wall, and slide them downward to feel the central nodes. Subsequently, you can palpate the apical and supraclavicular nodes if missed during the head and neck examination. While supporting the patient’s left arm in the same position, palpate the patient’s epitrochlear nodes, which are located medially about three centimeters above the elbow. Repeat the entire examination on the patient’s right using your left hand.

With the patient’s axilla and upper extremity examination complete, proceed to the lower extremities. This region includes the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, which are located high in the anterior thigh and drain various regions of the legs, abdomen, and perineum. These nodes are often large enough to palpate, even when normal, and can be subdivided into two groups: the horizontalgroup located just below the inguinal ligament and the vertical group located just below the femoral artery pulse.

In order to palpate these nodes, ask the patient to lay supine with their hips fully extended or slightly flexed. Once the patient is comfortable begin palpating the horizontalgroup of nodes just below the inguinal ligament. Move your hand along the entire length of the ligament, taking note of the nodes’ size, shape and firmness. Finally, palpate the vertical group of nodes, which is medial to the horizontal group and just below the femoral artery pulse. This concludes the lymph node examination. Thank the patient for their cooperation.

You have just watched JoVE’s video documenting the lymph node examinations of patients’ head and neck areas, axillae, upper extremities and lower extremities. You should now understand the systematic sequence of steps that every physician should follow in order to conduct an effective lymph node exam. As always, thanks for watching!