Trasformazione di cellule di E. coli tramite l'utilizzo di una procedura basata sul metodo del cloruro di calcio

English

Share

Overview

Fonte: Natalia Martin1, Andrew J. Van Alst1, Rhiannon M. LeVeque1e Victor J. DiRita1

1 Dipartimento di Microbiologia e Genetica Molecolare, Michigan State University

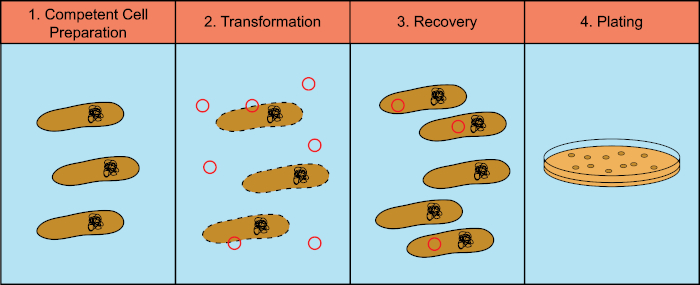

I batteri hanno la capacità di scambiare materiale genetico (acido desossiribonucleico, DNA) in un processo noto come trasferimento genico orizzontale. L’incorporazione di DNA esogeno fornisce un meccanismo attraverso il quale i batteri possono acquisire nuovi tratti genetici che consentono loro di adattarsi alle mutevoli condizioni ambientali, come la presenza di antibiotici o anticorpi (1) o molecole presenti negli habitat naturali (2). Esistono tre meccanismi di trasferimento genico orizzontale: trasformazione, trasduzione e coniugazione (3). Qui ci concentreremo sulla trasformazione, la capacità dei batteri di prendere il DNA libero dall’ambiente. In laboratorio, il processo di trasformazione ha quattro fasi generali: 1) Preparazione di cellule competenti, 2) Incubazione di cellule competenti con DNA, 3) Recupero di cellule e 4) Placcatura delle cellule per la crescita dei trasformanti (Figura 1).

Figura 1: Fasi generali del processo di trasformazione. Il processo di trasformazione ha quattro fasi generali: 1) Preparazione delle cellule competenti, 2) Incubazione con DNA, 3) Recupero delle cellule e 4) Cellule placcate per la crescita dei trasformanti.

Affinché si verifichi la trasformazione, i batteri riceventi devono essere in uno stato noto come competenza. Alcuni batteri hanno la capacità di diventare naturalmente competenti in risposta a determinate condizioni ambientali. Tuttavia, molti altri batteri non diventano competenti naturalmente, o le condizioni per questo processo sono ancora sconosciute. La capacità di introdurre il DNA nei batteri ha una serie di applicazioni di ricerca: generare più copie di una molecola di DNA di interesse, esprimere grandi quantità di proteine, come componente nelle procedure di clonazione e altri. A causa del valore della trasformazione in biologia molecolare, ci sono diversi protocolli volti a rendere le cellule artificialmente competenti quando le condizioni per la competenza naturale sono sconosciute. Due metodi principali sono utilizzati per preparare cellule artificialmente competenti: 1) attraverso il trattamento chimico delle cellule e 2) esponendo le cellule a impulsi elettrici (elettroporazione). Il primo utilizza diverse sostanze chimiche a seconda della procedura per creare attrazione tra il DNA e la superficie cellulare, mentre il secondo utilizza campi elettrici per generare pori nella membrana cellulare batterica attraverso i quali le molecole di DNA possono entrare. L’approccio più efficiente per la competenza chimica è l’incubazione con cationi bivalenti, in particolare calcio (Ca2+)(4,5) La competenza indotta dal calcio è la procedura che verrà descritta qui (6). Questo metodo viene utilizzato principalmente per la trasformazione dei batteri Gram-negativi e questo sarà il focus di questo protocollo.

La procedura di trasformazione chimica comporta una serie di passaggi in cui le cellule sono esposte a cationi per indurre competenza chimica. Questi passaggi sono successivamente seguiti da un cambiamento di temperatura – shock termico – che favorisce l’assorbimento di DNA estraneo da parte della cellula competente (7). Gli involucri cellulari batterici sono caricati negativamente. Nei batteri Gram-negativi come l’Escherichia coli,la membrana esterna è caricata negativamente a causa della presenza di lipopolisaccaride (LPS) (8). Ciò si traduce in repulsione delle molecole di DNA caricate negativamente in modo simile. Nell’induzione della competenza chimica, gli ioni calcio caricati positivamente neutralizzano questa repulsione di carica consentendo l’assorbanza del DNA sulla superficie cellulare (9). Il trattamento del calcio e l’incubazione con dna vengono effettuati su ghiaccio. Successivamente, viene eseguita un’incubazione a temperature più elevate (42°C), lo shock termico. Questo squilibrio di temperatura favorisce ulteriormente l’assorbimento del DNA. Le cellule batteriche devono essere nella fase di crescita media-esponenziale per resistere al trattamento di shock termico; in altre fasi di crescita le cellule batteriche sono troppo sensibili al calore con conseguente perdita di vitalità che diminuisce significativamente l’efficienza di trasformazione.

Diverse fonti di DNA possono essere utilizzate per la trasformazione. Tipicamente, i plasmidi, piccole molecole di DNA circolari a doppio filamento, vengono utilizzati per la trasformazione nella maggior parte delle procedure di laboratorio in E. coli. Affinché i plasmidi possano essere mantenuti nella cellula batterica dopo la trasformazione, devono contenere un’origine di replicazione. Ciò consente loro di essere replicati nella cellula batterica indipendentemente dal cromosoma batterico. Non tutte le cellule batteriche vengono trasformate durante la procedura di trasformazione. Pertanto, la trasformazione produce una miscela di cellule trasformate e cellule non trasformate. Per distinguere tra queste due popolazioni, viene utilizzato un metodo di selezione per identificare le cellule che hanno acquisito il plasmide. I plasmidi di solito contengono marcatori selezionabili, che sono geni che codificano un tratto che conferisce un vantaggio per la crescita (cioè resistenza a un antibiotico o a una sostanza chimica o salvataggio da un’auxotrofia di crescita). Dopo la trasformazione, le cellule batteriche vengono placcate su mezzi selettivi, che consentono solo la crescita delle cellule trasformate. Nel caso di cellule trasformate con un plasmide che conferisce resistenza a un determinato antibiotico, il mezzo selettivo sarà un mezzo di crescita contenente quell’antibiotico. Diversi metodi possono essere utilizzati per confermare che le colonie coltivate nei mezzi selettivi sono trasformanti (cioè hanno incorporato il plasmide). Ad esempio, i plasmidi possono essere recuperati da queste cellule utilizzando metodi di preparazione del plasmide (10) e digeriti per confermare le dimensioni del plasmide. In alternativa, la PCR della colonia può essere utilizzata per confermare la presenza del plasmide di interesse (11).

Lo scopo di questo esperimento è quello di preparare cellule chimicamente competenti di E. coli DH5α, utilizzando un adattamento della procedura del cloruro di calcio (12), e di trasformarle con il plasmide pUC19 per determinare l’efficienza di trasformazione. Il ceppo di E. coli DH5α è un ceppo comunemente usato nelle applicazioni di biologia molecolare. A causa del suo genotipo, in particolare recA1 e endA1, questo ceppo consente una maggiore stabilità dell’inserto e migliora la qualità del DNA plasmidico nei preparati successivi. Poiché l’efficienza di trasformazione diminuisce con l’aumentare delle dimensioni del DNA, il plasmide pUC19 è stato utilizzato in questo protocollo a causa delle sue piccole dimensioni (2686 bp) (vedi https://www.mobitec.com/cms/products/bio/04_vector_sys/standard_cloning_vectors.html per una mappa vettoriale). pUC19 conferisce resistenza all’ampicillina e, quindi, questo era l’antibiotico utilizzato per la selezione.

Procedure

Results

Although TE is dependent on many factors, non-commercial competent cell preparations, like this one, normally yield 106 to 107 transformants per microgram of plasmid. Therefore, this preparation, with a TE = 2.46 x 108 cfu/µg, yielded a TE well beyond the expected range. Additional protocols are available for making supercompetent cells when higher transformation efficiencies are required for a given application (13).

Analysis of the digestion of the plasmid DNA recovered from the transformed cells indicated that this plasmid has the expected size of pUC19 DNA (2686 bp).

Applications and Summary

Transformation is a powerful method for introducing exogenous DNA into bacterial cells that is key to many molecular biology applications in the laboratory. Additionally, it plays a major role in nature by allowing bacterial cells to exchange genetic material that could result in increased genetic variation and allow for acquisition of different beneficial traits for survival under a wide range of conditions. Many bacterial strains encode the genes required for natural competence. However, the conditions in which these genes are induced are still unknown. Further research is required to determine these conditions.

References

- Croucher, N. J. et al. Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science. 331 (6016):430-434. (2011)

- Borgeaud, S. et al. The type VI secretion system of Vibrio cholerae fosters horizontal gene transfer. Science. 347(6217):63-67. (2015)

- Burmeister, A. R. Horizontal Gene Transfer. Evol Med Public Health. 2015 (1):193-194. (2015)

- Weston A, Brown MG, Perkins HR, Saunders JR, Humphreys GO. Transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid: calcium-induced binding of deoxyribonucleic acid to whole cells and to isolated membrane fractions. J Bacteriol. 145 (2):780-7. (1981)

- Dagert M, Ehrlich SD. Prolonged incubation in calcium chloride improves the competence of Escherichia coli cells. Gene. 6 (1):23-8. (1979)

- Asif A, Mohsin H, Tanvir R, and Rehman Y. Revisiting the Mechanisms Involved in Calcium Chloride Induced Bacterial Transformation. Front Microbiol. 8:2169. (2017)

- Panja S, Aich P, Jana B, Basu T. How does plasmid DNA penetrate cell membranes in artificial transformation process of Escherichia coli? Mol Membr Biol. 25 (5):411-22. (2008)

- Silhavy, TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. The Bacterial Cell Envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2 (5): a000414. (2010)

- Panja S, Aich P, Jana B, Basu T. (2008) Plasmid DNA binds to the core oligosaccharide domain of LPS molecules of E. coli cell surface in the CaCl2-mediated transformation process. Biomacromolecules. 9 (9):2501-9.

- JoVE Science Education Database. Basic Methods in Cellular and Molecular Biology. Plasmid Purification. JoVE, Cambridge, MA. (2018)

- Bergkessel M and Guthrie C. Colony PCR. Methods in Enzymology. 529: 299-309. (2013)

- Sambrook J and Russell DW. Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.Protocol 25 (1.116-118). (2001)

- Wirth R, Friesenegger A, Fiedler S. Transformation of various species of gram-negative bacteria belonging to 11 different genera by electroporation. Molecular & General Genetics. 216 (1): 175-7. (1989)

Transcript

Bacteria are remarkably adaptable and one mechanism which facilitates this adaptation is their ability to take in external DNA molecules. One type of DNA that bacteria can uptake is called a plasmid, a circular piece of DNA that frequently contains useful information, such as antibiotic resistance genes. The process of bacteria being modified by new genetic information incorporated from an external source is referred to as transformation. Transformation can easily be performed in the laboratory using Escherichia coli, or E. coli.

In order to be transformed, E. coli cells must first be made competent, which means capable of taking in DNA molecules from their environment. The protocol for accomplishing this is surprisingly simple, a short incubation of the cells in a calcium chloride solution. This incubation causes the cells to become permeable to DNA molecules. After the cells are pelleted by centrifugation, the supernatant is removed. The plasmid DNA is now added to the competent cells. After incubating the cells with DNA, the mix is briefly heated to 42 degrees Celsius, followed by rapid cooling on ice. This heat shock causes the DNA to be transferred across the cell’s wall and membranes. The cells are then incubated in fresh media. Then, the bacteria are placed at 37 degrees to allow them to reseal their membranes and express resistant proteins.

Those cells which have taken in the plasmids will faithfully copy the DNA and pass it to their progeny and express any proteins that might be encoded by it, including antibiotic resistance mediators. Those resistance genes can be used as selectable markers to identify bacteria which have been successfully transformed because cells that have not taken up the plasmid will not express the resistance gene product. This means that when the cells are plated on a solid medium which contains the appropriate antibiotic, only cells that have taken up the plasmid will grow. Transformation of the cells in a growing colony can be further confirmed by culturing those cells in liquid media overnight to increase the yield before extracting the DNA from the sample. Once the DNA is isolated, a diagnostic restriction enzyme digest can be carried out. Because restriction enzymes cut DNA in predictable locations, running these digests on a gel should show a predictable pattern if the desired plasmid was successfully transformed. For example, if pUC19 is prepared and cut with the restriction enzyme HindIII, a single band of 2686 nucleotides should be seen on the gel.

In this lab, you will transform E. coli strain DH-5 Alpha with pUC19, and then confirm the successful transformation by DNA gel electrophoresis.

Before starting the procedure, put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves. Next, sterilize the workspace with 70% ethanol.

Now, prepare chemically competent cells by depositing a loopfull of bacteria onto a sterile LB agar plate and streaking the bacteria with a new loop. Then, incubate the plate at 37 degrees Celsius overnight. The next day, sterilize the bench top with 70% ethanol again, and remove the plate from the incubator.

Inoculate a single, well-isolated colony into 3 milliliters of LB broth in a tube with a sterile loop. Then, grow the culture at 37 degrees Celsius overnight, with shaking at 210 RPM. The next day, measure the optical density of the overnight culture with a spectrophotometer. Then, add 100 milliliters of LB broth to a one-liter flask, and inoculate it with the overnight culture at an optical density of 0. 01. Now, incubate the culture at 37 degrees Celsius with shaking, and check the OD600 every 15 to 20 minutes until the culture reaches mid-exponential growth phase.

After approximately three hours, transfer 50 milliliters of the culture to two ice-cold polypropylene bottles. Then, place the bottles back on ice for 20 minutes to cool. Next, recover the cells via centrifugation. Discard the supernatants and place the bottles upside down on a paper towel. Next, resuspend the bacterial pellet in five milliliters of ice-cold calcium chloride magnesium chloride solution and swirl carefully until the pellet has dissolved completely. Then, add another 25 milliliters of the solution to the dissolved bacterial pellet. Resuspend the other bacterial pellet as previously demonstrated. After this, repeat the centrifugation, and remove the supernatants.

If the competent cells are going to be directly transformed, resuspend each bacterial pellet in two milliliters of an ice-cold 0.1 molar calcium chloride solution by swirling the tubes carefully. To begin the transformation procedure, transfer 50 microliters of competent cells to two labeled 1.5 milliliter polypropylene tubes. Then, add one microliter of pUC19 plasmid DNA to one of the tubes. Mix gently, avoiding bubble formation, and incubate both tubes for 30 minutes on ice. After incubation, transfer the tubes to a heat block and incubate at 42 degrees Celsius for 45 seconds. Immediately transfer the tubes to ice, and incubate for two minutes. Now, add 950 microliters of SOC media to each tube and incubate them for one hour at 37 degrees Celsius to allow the bacteria to recover, and express the antibiotic resistant marker encoded in the plasmid.

To make a 1 to 100 dilution, add 990 microliters of SOC media and 10 microliters of cell suspension to a 1.5 milliliter tube. Then, make a 1 to 10 dilution by adding 900 microliters of SOC media and 100 microliters of cell suspension to a 1.5 milliliter tube. Next, plate 100 microliters of the diluted cell suspensions and 100 microliters of the negative control, onto separate selective plates containing ampicillin using a spreader and incubate the plates at 37 degrees Celsius for 12 to 16 hours. After incubation, count the colony-forming units, or CFUs, per plate, obtained through transformation, and record these data. To verify that the transformants have the pUC19 plasmid, pick a single, well-isolated colony from a plate with a sterile loop, and introduce it to a tube containing 3 milliliters of LB broth. Then, incubate the culture at 37 degrees Celsius with shaking, overnight. The next day, use a DNA mini prep kit to isolate DNA from 3 milliliters of the culture, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After completing the DNA mini prep, digest the 1 microgram of purified pUC19 with a restriction enzyme at 37 degrees Celsius for 1 hour. Now, load 20 microliters of a molecular weight ladder, 1 microgram of digested plasmid DNA, and 1 microgram of undigested plasmid DNA into consecutive wells of a 1% agarose gel containing 1 microgram per milliliter ethidium bromide. Then, run the gel for 1 hour at 95 volts. Finally, visualize the gel with a UV illuminator.

In this experiment, E. coli DH5 Alpha chemically competent cells were prepared using an adaptation of the calcium chloride procedure, and then transformed with the plasmid pUC19 to determine transformation efficiency. To calculate the transformation efficiency, use the recorded CFU counts for the 1 in 100 and 1 in 10 dilutions, and any other dilutions with CFU counts between 30 and 300. First, the recorded CFU count, 246 in this example, is divided by the amount of DNA, .0001 micrograms here, that was plated. Then, this number is divided by the dilution factor used to give the transformation efficiency in CFUs per microgram. In this example, a 1 to 10 dilution was used and 100 microliters of a 1 milliliter solution was plated, giving a final dilution factor of 0.01. In the undigested plasmid lane, the circular DNA may appear as two or three different bands of varying brightness. This is because the circular, uncut DNA may exist in several different conformation states, such as supercoiled, open circle, or more linear, and each of these move through the gel at different rates. Analysis of the recovered plasmid DNA digestion indicated that the plasmid used has an expected size of pUC19 DNA, 2,686 base pairs.