External Cephalic Version: Is it an Effective and Safe Procedure?

Summary

This article shows how to perform the external cephalic version (ECV) by two experienced obstetricians in the obstetric operating room in the presence of an anesthesiologist and a midwife. The ECV is carried out with analgesia and tocolysis. Two attempts are made under ultrasonography control.

Abstract

External cephalic version (ECV) is an effective procedure for reducing the number of cesarean sections. To date, there is no video publication showing the methodology of this procedure. The main objective is to show how to perform ECV with a specific protocol with tocolysis before the procedure and analgesia. Moreover, we describe and analyze the factors associated with successful ECV, and also compare to deliveries in the general pregnant population.

A retrospective and descriptive analysis of ECV carried out at the Hospital Clinico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca in Murcia (Spain) between 1/1/2014 and 12/31/2018 was assessed. The latest data available of labor deliveries in the local center, which is the biggest maternity department in Spain, were from 2018.

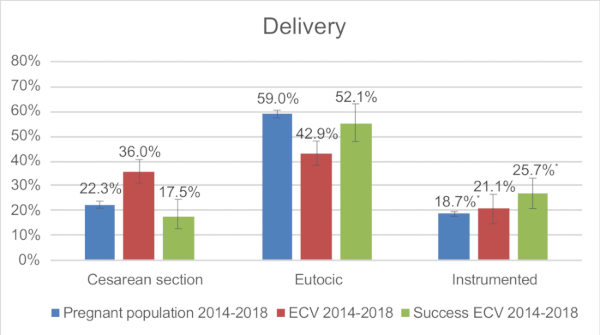

320 patients were recruited and 3 pregnant women were lost during the study. ECV was carried out at 37±3 weeks gestation. ECV was successful in 82.5% (N=264). 19 complications were reported (5.9%): 8 vaginal bleeding (2.5%), 9 fetal bradycardia (2.8%), 1 preterm rupture of membranes (0.3%) and 1 cord prolapse (0.3%). A previous vaginal delivery increases the success rate of ECV ORadjusted=3.03 (1.62-5.68). Maternal Body Mass Index (BMI) affects the success of ECV ORadjusted=0.94 (0.89-0.99). Patients with BMI>40 kg/m2 have an ORadjusted=0.09 (0.009-0.89) compared with those with BMI <25 kg/m2. If ECV was successful, the cesarean delivery index is 22.2% (17.5-27.6%), the eutocic delivery index is 52.1% (46.1-58.1%) and the instrumented vaginal delivery index is 25.7% (20.7-31.2%). There are no differences in cesarean and eutocic delivery indexes after successful ECV. However, a successful ECV is associated with a 6.29% increase in the instrumented delivery rate (OR=1.63).

ECV is an effective procedure to reduce the number of cesarean sections for breech presentations. Maternal BMI and previous vaginal delivery are associated with ECV success. Successful ECV does not modify the usual delivery pattern.

Introduction

External cephalic version (ECV) is a procedure for modifying the fetal position and achieving a cephalic presentation. The objective of the ECV is to offer an opportunity for cephalic delivery to occur, which is widely known to be safer than breech or cesarean section. ECV is usually performed before the active labor period begins. Factors associated with a higher ECV success rate include1,4: multiparity, a transverse presentation, black race, posterior placenta, amniotic fluid index higher than 10 cm.

However, ECV is not an innocuous procedure and may present7,11 intraversion complications such as premature rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding, transitory changes of fetal heart rate, cord prolapse, abruptio placentae, even stillbirth.

In this article, we analyzed ECVs performed under analgesia and tocolysis. To date, no video report has been published showing how to perform this procedure with analgesia and tocolysis. The main objective of this study is to show how ECV is performed. We also describe some key actions that could improve the procedural success. As a secondary objective, we analyzed the results of ECV obtained following the specific protocol with tocolysis and analgesia and compared the results with the literature. We also analyzed factors associated with ECV success rate, type of delivery and a comparison of the type of delivery in ECV pregnant women with non-ECV pregnant women were also included.

Protocol

This study was approved by the Clinic Research Committee of the "Virgen de la Arrixaca" at the University Clinical Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

1. Offer external cephalic version at consult (36 weeks)

- Identify the fetal position with an ultrasound.

- Apply ultrasound gel on the patient’s abdomen.

- Place the abdominal probe on the hypogastric region.

- Identify the fetal position.

- Offer external cephalic version.

- Have the patient sign informed consent.

2. Admit in the obstetric emergency room (≥37 weeks)

- Identify the fetal position with an ultrasound.

- Apply ultrasound gel on the patient’s abdomen.

- Place the abdominal probe on the hypogastric region.

- Identify the fetal position.

- Prepare the patient and check requirements (blood test and informed consent).

3. Admit in the obstetric delivery room

- Perform cardiotocography assessment for fetal well-being.

- Add 10 mL of ritodrine in 500 mL of glucose solution.

- 30 minutes before the procedure, administer 6 mg of ritodrine at 60 mL/h.

- Invite the patient to empty her bladder.

- Stop ritodrine perfusion before moving to the obstetric operating room.

4. External cephalic version procedure in obstetric operating room

- Move to the obstetric operating room.

- Monitor maternal vital signs (heartrate, EKG, temperature, noninvasive blood pressure, oxygen saturation).

- Identify the fetal position with an ultrasound.

- Apply ultrasound gel on the patient’s abdomen.

- Place the abdominal probe on the hypogastric region.

- Identify the fetal position.

- Position the patient in Trendelenburg (15°).

- Perform analgesia.

- Sedate the patient with 1-1.5 mg/kg propofol IV.

- Alternatively: Provide spinal anesthesia with 10 mL of 0.1% bupivacaine.

- External cephalic version procedure (2 attempts)

- Apply an abundant quantity of ultrasound gel on the patient’s abdomen.

- Place hands in the hypogastric region to identify the fetal buttocks (Obstetrician A).

- Elevate fetal buttocks (Obstetrician A).

- Place hands in the patient’s abdomen to locate the fetal head (Obstetrician B).

- Guide the fetal buttocks to the fundus (Obstetrician A).

- Consecutively direct the fetal head to the pelvis (Obstetrician B).

- Identify the fetal well-being with ultrasound.

- Place the abdominal probe on the abdomen.

- Identify the fetal heart.

- Observe the fetal heart rate for at least a minute.

- Check for vaginal bleeding.

- Identify the fetal position with ultrasound.

- Place the abdominal probe on the hypogastric region.

- Identify the fetal position.

5. Move to obstetric delivery room

- Perform cardiotocography assessment for fetal well-being for at least 4 hours.

- Discharge the patient.

6. Admit in obstetric emergency room (24 h post-procedure)

- Perform cardiotocography assessment for fetal well-being for 30 minutes.

Representative Results

Three hundred and twenty patients were recruited between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2018. Three patients were lost during the follow-up after the ECV because delivery was not carried out in our hospital.

Statistics were derived from the raw data. To study the differences between groups, unpaired Student's t-tests were used for quantitative variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables. All tests were two-tailed at a 0.05 significance level.

The mean age of all the patients was 33.18 years. 55.6% of the patients were nulliparous. Only 13 patients (4.1%) had a previous cesarean section. The mean maternal BMI was 25.1 kg/m2. The placenta was located in anterior wall of uterus in 63.5% of the patients, posterior in 30.8%, in fundus in 3.5% and in the lateral wall in 2.2%.

The ECV were performed at 37±3 weeks gestation, as an average, and the indication of ECV was breech presentation in 92.2% (N=295) of the patients and transverse presentation in 7.8% (N=25). ECV was successful in 82.5% (N=264) and failed in 17.5% (N=56) [Table 1]. Intraversion complications occurred in 5.94% (N=19) of the procedures: 9 had fetal bradycardia for more than 6 min (2.81%), 8 had vaginal bleeding (2.5%), 1 had preterm rupture of the membranes during the following 24 hours (0.31%), and 1 had cord prolapse (0.31%). No newborns were hospitalized in the neonatal unit nor the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

The factors related with the ECV procedure success in the logistic regression multivariant model (Table 3) were previous vaginal delivery with an adjusted OR=3.029 (1.62-5.68) and BMI with an adjusted OR=0.942 (0.89-0.99). Pregnant women with a previous vaginal delivery were 2.03 times more likely to have ECV success than nulliparous. If BMI was categorized (Table 4), patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 had an adjusted OR=0.091 (0.009-0.89) if they were compared with those with a BMI lower than 25 kg/m2 whereas a one unit increase in maternal BMI was associated with a 5.8% decrease in ECV success rate.

In the 261 successful ECV patient cohort (Table 2), 59.39% (N=155) of the patients had a spontaneous onset of labor, induction in 34.87% (N=91) of the patients, elective non-scheduled cesarean in 1.53% (N=4) of the patients due to unstable presentation, and intraversion cesarean in 4.21% (N=11) of the patients. 77.8% (N=203) of successful ECV patients ended the pregnancy with a vaginal delivery, in contrast with 22.2% (N=58) that had a cesarean delivery (including elective non-scheduled cesarean, intraversion cesarean section and urgent cesarean section during labor).

The type of delivery of the 261 successful ECV patients are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1: eutocic in 52.1% (N=136), instrumented in 25.7% (N=67), urgent cesarean section during labor in 16.5% (N=43), elective non-scheduled cesarean section in 1.5% (N=4) and intraversion cesarean section in 4.2% (N=11).

In patients with successful ECV, nulliparity was the only factor statistically associated with instrumented delivery with an adjusted OR=9.09 (4.54-18.20) following the logistic regression multivariant model (Table 2). Meanwhile, the BMI was the only factor statistically associated with an urgent cesarean section with an adjusted OR=1.11 (1.03-1.19).

Although, in the hospital during the 2018, 7,040 deliveries were carried out, just 7009 of them were correctly recorded in data base (Figure 1): 4136 (59.0%) were eutocic, 1309 (18.7%) were instrumented and 1564 (22.3%) had cesarean delivery.

In patients with a successful ECV (Table 2 and Figure 1), the cesarean section rate was 17.5% (11.9-23.0%), in contrast with general population cesarean section rate of 22.3% (21.3-23.3%). No statistical differences were found between successful ECV and general population cesarean section rate, OR=0.74 (0.53-1.03).

In patients with successful ECV, the eutocic delivery rate was 52.1% (46.1-58.1%), in comparison with the general population eutocic delivery rate of 59.0% (57.9-60.2%) [Table 2 and Figure 1]. No statistical differences were found between the successful ECV and the general population eutocic delivery rate, OR=0.86 (0.67-1.11).

In patients with a successful ECV, the instrumented delivery rate was 25.7% (20.7-31.2%), in contrast with the general population instrumented delivery rate of 18.7% (17.8-19.6%) [Table 2 and Figure 1]. Successful ECV was statistically associated with an increase of instrumented delivery rate if compared with the general population, OR=1.63 (1.22-2.17).

Between 2014 and 2018, 36,068 deliveries were carried out in the hospital, 7,423 of them were via cesarean section (20.6%). Thus, the ECV procedure has avoided 203 elective cesarean section during that period, a 0.56% decrease in the cesarean section rate.

Figure 1: Comparison of type of delivery: General pregnant population in 2018, ECV cohort between 2014-2018, Successful ECV cohort between 2014-2018. * Chi-squared test: p<0.05. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| ECV Result | |||||

| Success | Fail | ||||

| Mean/% (N) | CI 95% | Mean/% (N) | CI 95% | ||

| Age | 33.3 | (32.7-34.0) | 32.5 | (31.0-33.9) | |

| Gestational age at ECV | 37.4 | (37.3-37.5) | 37.3 | (37.2-37.4) | |

| Gravity | 2.1 | (1.9-2.3) | 1.7 | (1.4-2.1) | |

| Parity | 0.8 | (0.6-0.9) | 0.5 | (0.2-0.7) | |

| Nulliparity | 51.9% (137) | (45.9-57.9%) | 73.2% (41) | (60.7-83.4%) | |

| Previous cesarean section | 3.8% (10) | (2.0-6.6%) | 5.4% (3) | (1.5-13.6%) | |

| Maternal BMI | 24.8 | (24.2-25.4) | 26.4 | (24.8-28.0) | |

| Categorized Maternal BMI | Normal weight | 57.1% (145) | (51.0-63.1%) | 54.9% (28) | (41.3-68.0%) |

| Overweight | 31.1% (79) | (25.7-37.0%) | 23.5% (12) | (13.6-36.4%) | |

| Obesity grade 1 | 8.7% (22) | (5.7-12.6%) | 11.8% (6) | (5.1-22.7%) | |

| Obesity grade 2 | 2.8% (7) | (1.2-5.3%) | 3.9% (2) | (0.8-12.0%) | |

| Obesity grade 3 | 0.4% (1) | (0.04-1.8%) | 5.9% (3) | (1.7-14.9%) | |

| Estimated Fetal Weight before ECV (g) | 2818.7 | (2773.9-2863.5) | 2801.5 | (2715.3-2887.8) | |

| Placental location | Anterior | 62.7% (165) | (56.8-68.4%) | 67.3% (37) | (54.2-78.5%) |

| Posterior | 31.6% (83) | (26.1-37.4%) | 27.3% (15) | (16.9-40.0%) | |

| Fundus | 3.4% (9) | (1.7-6.2%) | 3.6% (2) | (0.8-11.2%) | |

| Lateral wall | 2.3% (6) | (1.0-4.6%) | 1.8% (1) | (0.2-8.2%) | |

| Previa | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | |

| ECV Indication | Breech | 90.9% (240) | (87.0-93.9%) | 98.2% (55) | (92.0-99.8%) |

| Transverse | 9.1% (24) | (6.1-13.0%) | 1.8% (1) | (0.2-8.0%) | |

| Analgesia | No | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | 0% (0) | (0-0%) |

| Sedation | 98.9% (261) | (97.0-99.7%) | 100% (56) | (0-0%) | |

| Spinal anesthesia | 1.1% (3) | (0.3-3.0%) | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | |

Table 1: External Cephalic Version characteristics: Success or Fail ECV. %: percentage. CI 95%: confidence interval 95%.

| ECV Result | ||||||

| Success | Fail | |||||

| Mean/% (N) | CI 95% | Mean/% (N) | CI 95% | |||

| Gestational age at delivery | 39.0 | (38.4-39.6) | 39.0 | (38.7-39.3) | ||

| Onset of labor | Spontaneous | 59.4% (155) | (53.4-65.2%) | 1.8% (1) | (0.2-8.0%) | |

| Induction | 34.9% (91) | (29.3-40.8%) | 1.8% (1) | (0.2-8.0%) | ||

| Elective cesarean | 1.5% (4) | (0.5-3.6%) | 89.3% (50) | (79.2-95.4%) | ||

| Intraversion cesarean | 4.2% (11) | (2.3-7.2%) | 7.1% (4) | (2.5-16.1%) | ||

| Type of delivery | Vaginal | 77.8% (203) | (72.5-82.5%) | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | |

| Eutocic | 52.1% (136) | (46.1-58.1%) | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | ||

| Instrumented | 25.7% (67) | (20.7-31.2%) | 0% (0) | (0-0%) | ||

| Cesarean | 22.2% (58) | (17.5-27.6%) | 100% (56) | (0-0%) | ||

| Urgent cesarean | 16.5% (43) | (12.4-21.3%) | 3.6% (2) | (0.8-11.0%) | ||

| ECV complications | 5.7% (15) | (3.4-9.0%) | 7.1% (4) | (2.5-16.1%) | ||

| Newborn weight (g) | 3276.9 | (3218.4-3335.3) | 3154.7 | (3050.2-3259.2) | ||

Table 2: Onset of labor and type of delivery. External Cephalic Version characteristics: Success or Fail ECV. %: percentage. CI 95%: confidence interval 95%.

| OR | p | 95% CI | adjustedOR | p | 95% CI | ||

| Previous vaginal delivery | 3.467 | 0.001 | (1.684-7.140) | 3.029 | 0.001 | (1.615-5.680) | |

| Maternal BMI | 0.911 | 0.007 | (0.851-0.975) | 0.942 | 0.044 | (0.888-0.998) | |

| Previous cesarean section | 0.706 | 0.619 | (0.179-2.786) | ||||

| Placental location | Anterior | 0.000 | 0.523 | ||||

| Posterior | 1.559 | 0.218 | (0.770-3.157) | ||||

| Fundus | 2.640 | 0.375 | (0.310-22.499) | ||||

| Lateral | 0.732 | 0.783 | (0.080-6.679) | ||||

| Estimated Fetal Weight before ECV (g) | 1.000 | 0.441 | (0.999-1.001) | ||||

Table 3: Logistic regression multivariant model of ECV results. OR: Odds ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. BMI: Body mass index. OR adjusted by previous vaginal delivery and maternal BMI.

| OR | p | 95% CI | |

| Maternal BMI less than 25 Kg/m2 | 1.000 | ||

| Maternal BMI between 25-30 Kg/m2 | 1.378 | 0.342 | (0.711-2.673) |

| Maternal BMI between 30-35 Kg/m2 | 0.816 | 0.668 | (0.322-2.067) |

| Maternal BMI between 35-40 Kg/m2 | 0.952 | 0.953 | (0.190-4.778) |

| Maternal BMI above 40 Kg/m2 | 0.091 | 0.040 | (0.009-0.897) |

Table 4: ECV results compared with categorized Body Mass Index. OR: Odds ratio. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. BMI: Body Mass Index.

Discussion

This article shows the procedure to carry out the ECV. The ECV procedure success rate in this study is 82.5% (78.1-86.4%), which is higher than the success rate found in international literature 49.0% (47-50.9%)1,2,3,4 or Spanish literature 53.49% (42.9-64.0%)5,6,7. This difference may be due to the use of tocolytic agents before the procedure, as proposed by Velzel et al.8, the gestational age at which ECV is performed, the experience acquired by the four obstetricians who carry out the ECV at the center, as suggested by Thissen D et al.9, the use of analgesia or the presence of an anesthesiologist and a midwife.

The use of external cephalic version in breech presentation, according to WHO10, certainly reduces the incidence of caesarean section, which is of special interest in those units where vaginal breech delivery is not a common practice.

There are some crucial steps in the protocol that make it different from others. Having the patient empty her bladder before the procedure, the use of tocolysis only before the ECV or analgesia with propofol or spinal anesthesia may contribute to the higher success rate obtained in the study.

The bladder volume plays an important role in the ECV success. Levin et al.11 highlighted the importance of starting the procedure with an empty bladder, reporting an OR=2.5 (1.42-4.34) for successful ECV if the bladder had a volume below 400 mL. All the participants in this study had an empty bladder.

Additionally, we propose the use of tocolysis with a beta-adrenergic agonist only before the procedure as tocolysis makes moving the fetus during ECV easier. The use of tocolysis has been reported previously in different studies, often used before and during ECV procedure. Vani et al.12 have reported a RR=1.9 (1.3-2.8) for successful ECV if the beta-adrenergic agonist is used during ECV as opposed to not using it. However, the use of tocolysis solely before the procedure has not been reported.

We performed ECV under analgesia or spinal anesthesia. In such a way, contraction of abdominal wall muscles is avoided or reduced and making it easier to move the fetus during ECV. Sullivan et al.13 reported no differences in the ECV success rate when the use of combined spinal anesthesia with intravenous analgesia is compared with only spinal anesthesia. Weiniger et al.14 reported an OR=4.97 (1.41-17.48) for successful ECV when spinal anesthesia is performed against no anesthesia.

Tocolysis and analgesia not only make it easier to move the fetus during ECV, but also increase the risk of vaginal bleeding and placental abruptio. A limitation of the study that should be noted is that complications such as vaginal bleeding occurred in 2.5% (N=8) of the patients. Grootscholten et al.15 reported 0.38% (N=51) cases of vaginal bleeding or placental abruption.

The rate of complications obtained in this study is 5.94% (3.7-8.9%), which is similar to the rate found in literature 6.1%1,15. No more than two attempts are proposed to perform ECV in the protocol. The National Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics recommends no more than 4 attempts16 to avoid abruptio placentae and fetal heart rate disturbance. We have reduced this to 2 attempts in order to be more cautious with the procedure due to the fact that tocolysis and analgesia might induce the obstetricians to apply greater forces.

BMI has been studied as a factor with influence in the ECV success rate17. In the study, for every unit of BMI the success rate of the ECV was reduced 7.8% with an adjusted OR=0.942 (0.89-0.99). Moreover, in the study, patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 (N=4) have far less chances of success in ECV than patients with BMI lower than 25 kg/m2 with an adjusted OR=0.091 (0.009-0.89). The results are in accordance with S. Chaudhary et al.17 that describe a decrease in ECV success rate in patients with a BMI higher than 40 kg/m2 compared to those with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 with an adjusted OR=0.621 (0.54-0.71)17. This finding may be because the adipose panniculus that may make the procedure difficult.

In the study, the patients who underwent an ECV, independently of the result of the procedure, had an eutocic delivery in 42.9% (37.5-48.4%) of the cases, instrumented delivery in 21.1% (16.6-25.6%) of cases, urgent cesarean section during labor in 14.2% (10.7-18.4%) of cases, and elective cesarean section in 17.0% (13.2-21.5%) of cases. In the literature, patients who underwent an ECV, independently of the result of the procedure, had an eutocic delivery in 33.1% (31.3-34.9%)1,2,18,19 of the cases, instrumented delivery in 10.5% (9.3-11.7%)1,2,18,19 of the cases, urgent cesarean section during labor in 18.5% (17.0-20.0%)1,2,18,19 of the cases, and elective cesarean section in 36.6% (34.7-38.5%)1,2,18,19 of the cases. Therefore, the study has a higher eutocic and instrumented delivery rate and a lower urgent cesarean section during labor rate than the literature reports. These differences might stem from the fact that the ECV success rate in this study is higher than published in the literature, therefore the vaginal delivery rate we obtained is also greater. It also should be noted that the differences in eutocic, instrumented and cesarean delivery rates could be explained due to the conservative management of the labor that is carried out in this center, so a higher spontaneous onset of labor, and a higher vaginal delivery rate are achieved with this approach.

After an ECV, the instrumented delivery rate increased compared to the general population, as de Hundt et al.18 described. In the study, ECV is associated with an instrumented delivery with OR=1.63 (1.22-2.17), while some authors18 reported an OR=1.4 (1.1-1.7). The reasons why women after a successful ECV have an increased risk for instrumented delivery compared with the general pregnant population remain unclear. Some studies have reported that breech fetuses are biologically different from cephalic-presenting fetuses with a lower weight, lower fetoplacental ratio and smaller head circumference18,20. These suggest that breech fetuses might tolerate labor worse and show earlier signs of fetal distress.

In the literature1,2,3,4, many factors are considered to influence in ECV success rate such as parity, amniotic fluid index, posterior placenta and breech presentation. However, we have just found a statistical association between parity and ECV success rate with an adjusted OR=3.029 (1.62-5.68) and maternal BMI with an adjusted OR=0.942 (0.89-0.99). Other factors have been associated with the failure of ECV such as: maternal age, gestational age at ECV, previous cesarean and estimated fetal weight1,2,3,4. However, no significantly statistical associations were found in the study. Future investigation is needed to evaluate different protocols of ECV including previous aspect and analgesia method.

Finally, we can conclude that ECV is an effective procedure to reduce the number of cesarean sections in fetuses with breech presentations. Maternal BMI and previous vaginal delivery are associated with success in ECV. Successful ECV does not modify the usual delivery pattern in comparison with the general population.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the midwives and anesthesiologists who have collaborated on this project. David Simó has specially collaborated with this project recording the procedure.

Materials

| Avalon FM20 Fetal monitor | Koninklijke Philips N.V | https://www.usa.philips.com/healthcare/product/HC862198/avalon-fm20-fetal-monitor | |

| Convex Array Probe 4C-RS | General Electric Health Care Company | ||

| Aquasonic® 100 Ultrasound Transmission Gel | Parker Laboratories, INC | https://www.parkerlabs.com/aquasonic-100.asp | |

| Propofol Lipuro (10 mg/mL Inject 20 mL) | B. Braun Medical, SA | ||

| Ritodrine Pre-par (10 mg/mL) | Laboratorio Reig Jofré, S.A | ||

| Viridia series 50 XM Fetal Monitor | Koninklijke Philips N.V | https://www.usa.philips.com/healthcare/product/HC865071/avalon-fm50-fetal-monitor | |

| Voluson P6 | General Electric Health Care Company | https://www.ge-sonostore.com/en/voluson/p6 |

References

- Melo, P., Georgiou, E. X., Hedditch, A., Ellaway, P., Impey, L. External cephalic version at term: a cohort study of 18 years’ experience. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 126, 493-499 (2019).

- Hofmeyr, G. J., Kulier, R., West, H. M. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4, 83 (2015).

- Isakov, O., et al. Prediction of Success in External Cephalic Version for Breech Presentation at Term. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 133 (5), 857-866 (2019).

- Ebner, F., et al. Predictors for a successful external cephalic version: a single centre experience. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 293 (4), 749-755 (2016).

- Castañer-Mármol, A. . Results of external cephalic version in our area without rutinary tocolysis. Review and implementation strategy. , (2015).

- Burgos, J., et al. Probability of cesarean delivery after successful external cephalic version. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 131 (2), 192-195 (2015).

- Muñoz, M., et al. External cephalic version at term: accumulated experience. Progresos de Obstetricia y Ginecología. 48 (12), 574-580 (2005).

- Velzel, J., et al. Atosiban versus fenoterol as a uterine relaxant for external cephalic version: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 356 (26), 6773 (2017).

- Thissen, D., Swinkels, P., Dullemond, R. C., van der Steeg, J. W. Introduction of a dedicated team increases the success rate of external cephalic version: A prospective cohort study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 236 (3), 193-197 (2019).

- Hindawi, I. Value and pregnancy outcome of external cephalic versión. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 11 (4), 633-639 (2005).

- Levin, G., Rottenstreich, A., Weill, Y., Pollack, R. N. The role of bladder volume in the success of external cephalic version. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 230, 178-181 (2018).

- Vani, S., Lau, S. Y., Lim, B. K., Omar, S. Z., Tan, P. C. Intravenous salbutamol for external cephalic version. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 104, 28-31 (2009).

- Sullivan, J. T., et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of combined spinal-epidural analgesia on the success of external cephalic version for breech presentation. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 18, 328-334 (2009).

- Weiniger, C. F., et al. Randomized controlled trial of external cephalic version in term multiparae with or without spinal analgesia. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 104 (5), 613-618 (2010).

- Grootscholten, K., Kok, M., Oei, S. G., Mol, B. W., van der Post, J. A. External cephalic version-related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 112 (5), 1143-1151 (2008).

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia. External cephalic version (updated March 2014). Progresos de Obstetricia y Ginecología. 58 (7), 337-340 (2015).

- Chaudhary, S., Contag, S., Yao, R. The impact of maternal body mass index on external cephalic version success. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 32, 21-59 (2019).

- de Hundt, M., Velzel, J., de Groot, C. J., Mol, B. W., Kok, M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 123 (6), 1327-1334 (2014).

- Krueger, S., et al. Labour Outcomes After Successful External Cephalic Version Compared With Spontaneous Cephalic Version. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Canada. 40, 61-67 (2018).

- Kean, L. H., Suwanrath, C., Gargari, S. S., Sahota, D. S., James, D. K. A comparison of fetal behaviour in breech and cephalic presentations at term. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 106, 1209-1213 (1999).