- 00:01Concepts

- 04:08Preparation of Plates and Bacteria

- 06:04Determining MIC Using E-Test

- 07:01Synergy Testing: Cross Approach

- 07:47Synergy Testing: Non-Cross Approach

- 08:56MIC Determination Using Broth Dilution

- 10:33Data Analysis: Broth Microdilution

- 11:10Data Analysis and Results: Synergy Testing

Tests de sensibilité aux antibiotiques : Utilisation du ETEST pour déterminer la CMI de deux antibiotiques et évaluer la synergie des antibiotiques

English

Share

Overview

Source: Anna Blàckberg1, Rolf Lood1

1 Département des sciences cliniques Lund, Division de médecine de l’infection, Centre biomédical, Université de Lund, 221 00 Lund Suède

La connaissance des interactions entre les antibiotiques et les bactéries est importante pour comprendre comment les microbes évoluent la résistance aux antibiotiques. En 1928, Alexander Fleming découvre la pénicilline, un antibiotique qui exerce sa fonction antibactérienne en interférant avec la régénération de la paroi cellulaire (1). D’autres antibiotiques avec divers mécanismes d’action ont été découverts par la suite, y compris des médicaments qui inhibent la réplication de l’ADN et la traduction des protéines chez les bactéries; cependant, aucun nouvel antibiotique n’a été développé ces dernières années. La résistance aux antibiotiques actuels a augmenté, ce qui a entraîné des maladies infectieuses graves qui ne peuvent pas être traitées efficacement (2). Ici, nous décrivons plusieurs méthodes pour évaluer la résistance aux antibiotiques dans les populations bactériennes. Chacune de ces méthodes fonctionne, quel que soit le mécanisme d’action des antibiotiques utilisés, parce que la mort bactérienne est le résultat mesuré. La résistance aux antibiotiques est non seulement rapidement disséminée spécifiquement dans les milieux hospitaliers, mais aussi dans toute la société. Afin d’étudier de tels moyens de résistance, différentes méthodes ont été développées, y compris le test Epsilomètre (E-test) et le test de dilution du bouillon (3).

Le test électronique est une méthode bien établie et un outil rentable qui quantifie les données de concentration inhibitrice minimale (MIC), la plus faible concentration d’un antimicrobien qui inhibe la croissance visible d’un micro-organisme. Selon la souche bactérienne et les antibiotiques utilisés, la valeur du MIC peut varier entre le sous-g/mL et le 4. Le test Électronique est effectué à l’aide d’une bande de plastique contenant un gradient antibiotique prédéfini, qui est imprimé avec l’échelle de lecture du MIC en ‘g/mL. Cette bande est directement transférée sur la matrice d’agar lorsqu’elle est appliquée sur la plaque d’agar inoculée. Après l’incubation, une zone d’inhibition elliptique symétrique est visible le long de la bande à mesure que la croissance bactérienne est empêchée. LE MIC est défini par la zone d’inhibition, qui est le point de terminaison où l’ellipse croise la bande. Une autre méthode courante pour déterminer LE MIC est la méthode de dilution des microbroths. La dilution du microbroth incorpore différentes concentrations de l’agent antimicrobien ajouté à un milieu bouillon contenant des bactéries inoculées. Après l’incubation, le MIC est défini comme la plus faible concentration d’antibiotiques qui empêche la croissance visible (5). Il s’agit également d’une méthode quantitative qui peut être appliquée à plusieurs bactéries. Les inconvénients de cette méthode comprennent la possibilité d’erreurs lors de la préparation des concentrations des réactifs et le grand nombre de réactifs requis pour l’expérience. La mesure de la résistance aux antibiotiques est impérative du point de vue clinique et de la recherche, et ces méthodes in vitro d’étude de la résistance sont discutées et présentées ci-dessous.

Le profil de résistance pour une bactérie spécifique peut être appliqué afin d’optimiser le traitement antibiotique afin de déterminer si un patient bénéficierait d’un traitement combiné par rapport à un traitement unique. Pour l’utilisation de plus d’un antibiotique à la fois, il est impératif de connaître leurs interactions les uns avec les autres et s’ils ont un effet additif, synergique ou antagoniste. Un effet additif peut être vu lorsque l’effet articulaire des antibiotiques équivaut à la puissance des antibiotiques individuels administrés à dose égale. La synergie entre les antibiotiques, d’autre part, est présente lorsque l’effet articulaire des antibiotiques est plus puissant que si le médicament serait administré seul (6). L’application de combinaisons de traitement antimicrobien est utilisée pour éviter l’apparition de la résistance aux antimicrobiens afin d’améliorer l’effet du traitement antibiotique individuel (7). La connaissance de l’antagonisme est également aussi importante pour prévenir l’utilisation inutile de combinaisons d’antimicrobiens. La méthodologie de test électronique offre des moyens simples et de plusieurs façons de déterminer la synergie et l’antagonisme possibles entre les différents agents antimicrobiens. Afin de faire face à la prolifération des agents pathogènes résistants aux antibiotiques, la connaissance des mécanismes synergiques et antagonistes possibles de certains antibiotiques est importante, ce qui entraîne une efficacité clinique et lutte contre la multirésistance aux médicaments.

La détermination de la synergie à l’aide des tests e peut être divisée en deux approches générales : les tests croisés et non croisés. Bien que les deux tests de synergie s’appuient sur la connaissance antérieure des valeurs individuelles du MIC, les deux approches sont légèrement différentes en méthodologie et en approche conceptuelle. Dans un test de synergie non croisé, le premier antibiotique de la paire à être testé est placé sur une plaque d’agar inoculée avec des bactéries. Après avoir permis aux antibiotiques de la première bande infuser la plaque (par exemple après 1 heure), la bande est enlevée et une nouvelle bande contenant le deuxième antibiotique est placé au même endroit que le premier, en veillant à placer les deux valeurs MIC individuelles sur le dessus de chaque ot son. La zone d’inhibition qui en résulte peut ensuite être analysée comme décrite ci-dessus, et la synergie calculée sur la base de l’équation 1.

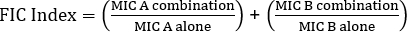

Équation 1 – Concentrations inhibitrices fractionnelles (FIC)

Les valeurs de la marque sont des valeurs qui démontrent une synergie.

Tout en récompensant l’examinateur avec des plaques faciles à analyser, la méthode est un peu laborieuse et longue en raison du changement de bandes, ainsi que la nécessité d’utiliser deux plaques par expérience. Au lieu de cela, un test croisé est souvent utilisé. Au lieu d’ajouter les deux bandes d’essai E différentes par la suite sur l’autre (après l’enlèvement de la première), les deux sont placés simultanément, mais sous la forme d’une croix (angle de 90 degrés), avec les deux valeurs MIC précédemment déterminées formant l’angle de 90 degrés. Par cette approche, une seule plaque est nécessaire par test de synergie, ainsi que moins de travail, ce qui en fait un choix préféré en dépit d’être un peu plus difficile à analyser. Les nouvelles valeurs du MIC dans l’approche combinée des antibiotiques peuvent être visualisées comme les zones d’inhibition modifiées, après quoi la synergie peut être déterminée par l’équation 1.

l’enlèvement de la première), les deux sont placés simultanément, mais sous la forme d’une croix (angle de 90 degrés), avec les deux valeurs MIC précédemment déterminées formant l’angle de 90 degrés. Par cette approche, une seule plaque est nécessaire par test de synergie, ainsi que moins de travail, ce qui en fait un choix préféré en dépit d’être un peu plus difficile à analyser. Les nouvelles valeurs du MIC dans l’approche combinée des antibiotiques peuvent être visualisées comme les zones d’inhibition modifiées, après quoi la synergie peut être déterminée par l’équation 1.

Au lieu d’utiliser une approche de plaque d’agar, une approche de microbroth peut souvent être préférentielle en raison de sa plus grande flexibilité (par exemple, la capacité de choisir des concentrations spécifiques d’antibiotiques en dehors des limites d’une bande de test électronique). En outre, les tests de microbroth sont suggérés pour être plus sensibles en raison de leur distribution uniforme d’antibiotiques dans une solution liquide, ne dépend pas de la dissociation dans une phase solide (plaque d’agar). Les puits dans une microplaque de 96 puits seront inoculés avec un nombre fixe de bactéries (106 cfu/mL : la concentration bactérienne peut être estimée par des mesures OD600 nm, des normes de turbidité, ou par des échantillons de placage de 10x dilutions bactériennes en série), et antibiotiques dans différentes dilutions seront ajoutés aux puits. De même, pour les bandes e-test MIC est déterminé comme l’intersection (bien / spot) avec la plus faible concentration d’antibiotiques inhibant la croissance visible des bactéries.

Objectif expérimental

- Le projet ci-dessous décrit les stratégies visant à déterminer les valeurs MIC de la pénicilline G et de la gentamicine du groupe G de Streptococcus par deux méthodes différentes, le test électronique et la dilution du microbroth. Pour l’essai électronique, les plaques d’agar De Mueller-Hinton inoculées avec le groupe G de Streptococcus ont été employées en combination avec des bandes de gradient de la pénicilline G et/ou de la gentamicine ; tandis que MH-broth avec 50% de sang de cheval lysé et 20 mg/mL -NAD ont été utilisés avec des antibiotiques solubles avec streptocoque groupe G dans une approche de microbroth.

Matériaux

- Colonies bactériennes sur une plaque d’agar de sang, stockées 7 jours dans 4 oC

- Plaques d’agar de sang

- 0.5 Norme McFarland

- 1% BaCl2

- 1% H2SO4

- Tube salin (2 mL)

- Applicateur à pointe de coton

- Plaques d’agar Mueller-Hinton (plaques MHA)

- Bouillon MH avec 50% de sang de cheval lysé et 20 mg/mL-NAD (MH-F)

- E-test pénicilline/gentamicin (ou antibiotiques d’intérêt) (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France, Suède)

- Pénicilline/gentamicine (ou antibiotiques d’intérêt (poudre/solution))

Remarque : Les médias spécifiques utilisés pour la croissance bactérienne peuvent varier selon les espèces.

Procedure

Results

MIC values in E-test

Individual MIC values were identified in Figure 1 as 0.094 μg/mL for penicillin G and 8 μg/mLfor gentamicin. For synergy tests, both demonstrated an MIC value for penicillin G of 0.064 μg/mL (Figures 2, 3), while gentamicin had an MIC 4 μg/mL for cross and non-cross tests. Note a slight discrepancy between the cross and non-cross tests may occur due to the different incubation times of the strips in the two settings.

Calculation of synergy

The equation for FIC is:

= 1.18 >0.5 (no synergy)

= 1.18 >0.5 (no synergy)

MIC determination in broth

Cloudiness of the wells indicated bacterial growth, and thus no inhibition occurred. The first clear well with penicillin G (Figure 4) contained 0.12 μg/mL penicillin G, and hence this was the MIC value. For gentamicin the first clear well was present at 8 μg/mL gentamicin. The penicillin G value was slightly higher than when using an E-test, due to the higher resolution of the strip (e.g. based on a 1.5x factor serial dilution, not a 2x factor).

Inoculum size

To determine the inoculum size, an approach as outlined in Figure 5 and 6 was used. Colonies were counted in the D-row (1000x dilution), adding up to 7, 8, and 8 in the triplicate series with a mean value of 7.67 cfu. The number of colonies neeed to be multiplied with the dilution factor (e.g. 1000x), as well as with 100 to obtain cfu/mL, giving an inoculum size of approximately 8 x 105, well within the targeted inoculum size of 105-6 cfu/mL.

Applications and Summary

Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide health problem. In order to determine resistance mechanisms of microbes, methods testing for synergy and antagonism with different antibiotics is crucial. The E-test method is rapid, easy to replicate, and can be used to investigate any synergistic potential of combination therapies. The broth dilution method can also be assessed to predict bactericidal activity. In order to investigate the resistance mechanisms of different microbes, knowledge of synergistic and antagonistic antibiotic interactions is crucial. Combining antibiotics may be a strategy to increase treatment efficacy and face antibiotic resistance. In the tests performed here, we were able to determine the MIC values of penicillin G and gentamicin for group G Streptococcus. We also demonstrated that the two antibiotics do not display synergistic effects, thus would not be a preferred treatment option for such infections.

References

- Tan SY, Tatsumura Y. Alexander Fleming (1881-1955): Discoverer of penicillin. Singapore Medical Journal. 56 (7):366-7. (2015)

- Aminov RI. A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Frontiers in Microbiology. 1:134. (2010)

- Pankey GA, Ashcraft DS, Dornelles A. Comparison of 3 E-test (®) methods and time-kill assay for determination of antimicrobial synergy against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella species. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 77 (3):220-6. (2013)

- EUCAST: European Committee On Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (www.eucast.org).

- Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nature Protocols. 3 (2):163-75. (2008)

- Doern CD, When does 2 plus 2 equal 5? A review of antimicrobial synergy testing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52 (12):4124-28. (2014)

- Worthington RJ, Melander C. Combination approaches to combat multi-drug resistant bacteria. Trends in Biotechnology. 31 (3):177-84. (2013)

Transcript

Antibiotic susceptibility is defined as the sensitivity of a bacteria to antibiotics and can be measured using a broth dilution test or an Epsilometer test, also called an E-test.

In the broth dilution method, a standardized number of bacteria are added to a growth media containing serial antibiotic dilutions. If susceptible, the bacteria cannot grow at the higher antibiotic concentrations but continue to multiply at the lower antibiotic concentrations, causing media to turn turbid. The lowest antibiotic concentration at which the bacteria can no longer survive or multiply is referred to as the minimum inhibitory concentration, or MIC, value of the antibiotic for the given bacteria.

In an E-test, a plastic strip impregnated with a predefined gradient of antibiotic is applied over a freshly spread lawn of bacteria on a Mueller-Hinton agar, or MH-A, Petri plate. The antibiotic diffuses out into the agar media, where it is taken up by the bacteria. If susceptible, the bacteria cannot multiply and will die off, forming a clear zone around the E-strip, which is referred to as the growth inhibition zone. At the point where the growth intersects with the E-strip, the corresponding value on the scale gives the MIC value of the antibiotic.

Often antibiotics are used in combination to prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria. This often results in a synergistic, rather than additive, effect. Synergistic means that the combined effect of the two antibiotics is greater than the sum of their individual activities. However, the effect is considered significant only when the MIC value of the antibiotic combination decreases by at least two-fold. This criterion is evaluated by calculating the fractional inhibitory concentration, or FIC, index. By summing the ratio of the MIC of each antibiotic in combination with the MIC of each antibiotic individually, an FIC index less than 0.5 indicates synergy.

Antibiotic synergy can be measured using two E-test based methods: a non-cross test or a cross test. In a non-cross test, first, the E-strips for two different antibiotics with predetermined MIC values are applied to two separate plates. After the antibiotics have diffused into the medium, the original E-strips are removed and the E-strips for the alternate antibiotics are placed such that their MIC scales lay exactly over the MIC scales of the previous strips. In a cross test, which is a faster version of the non-cross test, the E-strips of the two antibiotics are placed together in a cross formation, such that the scales of their MIC marks form a 90 degree angle at the intersection. Following incubation in both techniques, the MIC value of each antibiotic in combination with the other antibiotic is read at the point where the growth inhibition zone intersects with the edge of the E-strip. Then, the FIC index is calculated.

This video will demonstrate how to determine the MIC value of a given antibiotic for a given bacteria using an E-test and a micro broth dilution test. You will also learn how to determine synergy between two antibiotics using a cross test and a non-cross test.

To begin, put on any appropriate personal protective equipment, including laboratory gloves and a lab coat. Next, sterilize the work space using 70% ethanol. Next, collect 15 milliliters of sterile Mueller-Hinton broth with 50% lysed horse blood and 20 milligrams per milliliter beta-nicotinamide. And five to eight Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Now, to prepare a McFarland turbidity standard number 0.5, measure out 9.95 milliliters of 1% sulfuric acid solution. Then, add 50 microliters of 1% barium chloride solution to the sulfuric acid solution. Vortex the solution well to obtain a turbid suspension. Cover the tube with aluminum foil and set it aside. Next, dispense one milliliter of saline solution into a 15 milliliter tube.

Use a sterile loop to scrape up a sample of the bacterial growth from your bacterial test plate, here, Streptococcus group G. Then, place the bacteria-laden loop into the saline solution, stir gently, and then vortex the tube well. Now, place the bacterial suspension and McFarland turbidity standards side by side and compare them for turbidity equivalence. Add either additional saline or bacterial colonies until the bacterial suspension’s turbidity matches that of the standard. Once the desired turbidity is obtained, dip a sterile cotton tip applicator into the bacterial suspension. To inoculate the MH-A plate, swab the entire surface of the plate gently with a zigzag motion. Next, label the bottom sides of the plates with the name of the bacteria and the date.

To begin, take out a penicillin G E-test strip, holding it by the edge with forceps. Gently place strip into the center of the freshly swabbed MH-A plate and replace the lid. In this example, a second antibiotic, gentamicin, is also tested. Thus, the strip placement process is repeated with the second plate and a gentamicin E-test strip. To determine the results of the E-test, collect the first plate that contains the penicillin G E-test strip. Now, determine the point where the inhibition zone intersects with the antibiotic strip. Read the corresponding numerical value on the scale. This value represents the MIC value of penicillin G. Determine the MIC value for gentamicin in the same manner.

To begin, inoculate an MH-A plate with Streptococcus group G strain bacteria. Label the bottom of the plate with the name of the bacteria, antibiotics to be used, and the date. Now, place an E-test strip for the antibiotic of interest in the center of the plate. Then, hold the second test strip at a 90 degree angle to the first strip and locate its MIC mark. Gently lay the second E-strip over the first at the point where the two MIC values intersect. Once the strips are placed, do not move them. Next, incubate the plates at 37 degrees celsius for 18 to 20 hours.

After inoculating two MH-A plates, with Streptococcus group G strain bacteria, place an E-test strip for one antibiotic on the surface of one plate. Then, place an E-test strip for the other antibiotic on the second plate as demonstrated. Using a plastic inoculation loop, mark the MIC value of each antibiotic on the surface of its respective plate. Next, cover the plates and incubate them at room temperature for one hour. After this, use forceps to remove the E strips. Next, collect one of the plates and an E-test strip for the other antibiotic. Hold the E-test strip over the imprint left by the first strip and locate the point where the MIC value on the E strip aligns with the marked line. Gently place the strip at this intersecting point. Repeat this process for the second plate and incubate both plates at 37 degrees celsius for 18 to 20 hours.

First, obtain a bacterial suspension with an established bacterial concentration and dilute the culture in MHF broth to achieve an OD600 of 0.003. Next, weigh out 16 milligrams of penicillin G and 128 milligrams of gentamicin. Transfer each weighed dry antibiotic into 215 milliliter conical tubes. Add 10 milliliters of distilled water to each of the conical tubes and mix well by vortexing. Label the tubes with the antibiotic name and concentration.

Performing the assay in triplicate, add 400 microliters of the working bacterial solution into the first wells of three rows of a 96-well microtiter plate. Next, add 200 microliters of the working bacterial solution in MHF broth to the wells of the three rows. Now, to generate a two-fold serial antibiotic dilution, first add four microliters of antibiotic stock to the first well, generating a 100 fold dilution. Sequentially, transfer 200 microliters of bacteria-antibiotic solution to each well, beginning from the first well through the second to last well in each row, ensure proper mixing by pipetting two to three times after every transfer. Discard the final 200 microliters of bacteria-antibiotic solution.

To determine the results of the broth micro dilution test for penicillin G, first locate the wells that exhibit no visible bacterial growth, indicated by a lack of turbidity. From these wells, identify the well with the lowest antibiotic concentration. This represents the MIC value of penicillin G for the tested bacteria. The MIC value of gentamicin can be determined using the same assay and technique.

To determine the results of the non-cross test, collect the first plate, which contains a penicillin G E strip. Then, determine the point where the growth inhibition zone intersects with the antibiotic strip. The corresponding value on the scale represents the MIC value for penicillin G in combination with gentamicin. In this example, the MIC value in combination is 0.064 micrograms per milliliter.

Now, collect the second plate, which contains the gentamicin E strip, and determine the MIC value in combination as previously demonstrated. To evaluate the effect of combination, first calculate the fractional inhibitory concentration or FIC for penicillin G by dividing the MIC in combination by the MIC of the antibiotic alone. Repeat this process for gentamicin. Then, calculate the FIC index using the equation shown here. A two-fold reduction in the MIC value in combination yields an FIC index value that is less than or equal to 0.5 and demonstrates synergy between penicillin G and gentamicin. In this case, the calculated FIC value is 1.18 which is greater than 0.5. Thus, the results do not demonstrate synergy between penicillin G and gentamicin against the Streptococcus group G strain.

To determine the results of the cross test, first determine the point where the growth inhibition zones intersect with their respective E strips. Read the numerical value on each E-test strip that corresponds to this intersection point. These values represent the MIC value in combination for penicillin G and gentamicin. Next, to evaluate the effect of the combination, calculate the FIC index using the equation shown here. In this example, the calculated FIC value is 1.18, which is greater than 0.5. This means that penicillin G and gentamicin do not act synergistically against the Streptococcus group G strain.