- 00:01Concepts

- 04:08Preparation of Plates and Bacteria

- 06:04Determining MIC Using E-Test

- 07:01Synergy Testing: Cross Approach

- 07:47Synergy Testing: Non-Cross Approach

- 08:56MIC Determination Using Broth Dilution

- 10:33Data Analysis: Broth Microdilution

- 11:10Data Analysis and Results: Synergy Testing

Pruebas de susceptibilidad a los antibióticos: Pruebas con epsilometro para determinar los valores de la CMI de dos antibióticos y evaluar la sinergismos

English

Share

Overview

Fuente: Anna Bl’ckberg1, Rolf Lood1

1 Departamento de Ciencias Clínicas Lund, División de Medicina de Infecciones, Centro Biomédico, Universidad de Lund, 221 00 Lund Suecia

El conocimiento de las interacciones entre antibióticos y bacterias es importante para entender cómo los microbios evolucionan la resistencia a los antibióticos. En 1928, Alexander Fleming descubrió la penicilina, un antibiótico que ejerce su función antibacteriana interfiriendo con la regeneración de la pared celular (1). Otros antibióticos con diversos mecanismos de acción han sido descubiertos posteriormente, incluyendo medicamentos que inhiben la replicación del ADN y la traducción de proteínas en bacterias; sin embargo, no se han desarrollado nuevos antibióticos en los últimos años. La resistencia a los antibióticos actuales ha ido en aumento, lo que ha dado lugar a enfermedades infecciosas graves que no pueden tratarse eficazmente (2). Aquí, describimos varios métodos para evaluar la resistencia a los antibióticos en poblaciones bacterianas. Cada uno de estos métodos funciona, independientemente del mecanismo de acción de los antibióticos utilizados, porque la muerte bacteriana es el resultado medido. La resistencia a los antibióticos no sólo se disemina rápidamente específicamente a través de los entornos hospitalarios, sino también en toda la sociedad. Con el fin de investigar estos medios de resistencia, se han desarrollado diferentes métodos, incluyendo la prueba del epsilometro (prueba E) y la prueba de dilución del caldo (3).

La prueba E es un método bien establecido y es una herramienta rentable que cuantifica los datos de la concentración mínima de inhibidores (MIC), la concentración más baja de un antimicrobiano que inhibe el crecimiento visible de un microorganismo. Dependiendo de la cepa bacteriana y de los antibióticos utilizados, el valor de la MIC puede variar entre sub g/ml y >1000 g/ml (4). La prueba E se realiza utilizando una tira de plástico que contiene un degradado antibiótico predefinido, que se imprime con la escala de lectura MIC en g/ml. Esta tira se transfiere directamente en la matriz de agar cuando se aplica a la placa de agar inoculada. Después de la incubación, una zona de inhibición elíptica simétrica es visible a lo largo de la tira a medida que se evita el crecimiento bacteriano. MIC se define por el área de inhibición, que es el punto final donde la elipse interseca la tira. Otro método común para determinar el MIC es el método de dilución de microcalina. La dilución de microcalina incorpora diferentes concentraciones del agente antimicrobiano añadido a un medio de caldo que contiene bacterias inoculadas. Después de la incubación, MIC se define como la concentración más baja de antibióticos que impide el crecimiento visible (5). También es un método cuantitativo y se puede aplicar a varias bacterias. Las desventajas de este método incluyen la posibilidad de errores al preparar las concentraciones de los reactivos y el gran número de reactivos necesarios para el experimento. La medición de la resistencia a los antibióticos es imprescindible tanto desde una perspectiva clínica como de investigación, y estos métodos in vitro para investigar la resistencia se discuten y se muestran a continuación.

El perfil de resistencia de una bacteria específica se puede aplicar con el fin de optimizar el tratamiento antibiótico para determinar si un paciente se beneficiaría del tratamiento combinado frente a la terapia única. Para el uso de más de un antibiótico a la vez, es imperativo conocer sus interacciones entre sí y si tienen un efecto aditivo, sinérgico o antagónico. Un efecto aditivo se puede ver cuando el efecto articular de los antibióticos es igual a la potencia de los antibióticos individuales dados a una dosis igual. La sinergia entre los antibióticos, por otro lado, está presente cuando el efecto articular de los antibióticos es más potente que si el medicamento se administrara solo (6). La aplicación de combinaciones de tratamiento antimicrobiano se utiliza para evitar la aparición de resistencia a los antimicrobianos, por lo tanto, para mejorar el efecto del tratamiento antibiótico individual (7). El conocimiento del antagonismo también es tan importante para prevenir el uso innecesario de combinaciones antimicrobianas. La metodología de prueba electrónico ofrece formas sencillas y varias de determinar posibles sinergias y antagonismo entre diferentes agentes antimicrobianos. Con el fin de hacer frente a la proliferación de patógenos resistentes a los antibióticos, el conocimiento de los posibles mecanismos sinérgicos y antagónicos de ciertos antibióticos es importante dando lugar a la eficacia clínica y luchando contra la resistencia multifármaco.

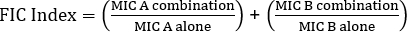

La determinación de la sinergia mediante pruebas E puede dividirse en dos enfoques generales: pruebas cruzadas y no cruzadas. Si bien ambas pruebas de sinergia se basan en el conocimiento previo de los valores individuales del MIC, los dos enfoques son ligeramente diferentes en metodología y enfoque conceptual. En una prueba de sinergia no cruzada, el primer antibiótico en el par a probar se coloca en una placa de agar inoculada con bacterias. Después de permitir que los antibióticos de la primera tira infundan la placa (por ejemplo, después de 1 hora), se retira la tira y se coloca una nueva tira que contiene el segundo antibiótico en el mismo lugar que la primera, asegurándose de colocar los dos valores individuales de MIC encima de cada ot Su. La zona de inhibición resultante se puede analizar como se describió anteriormente, y la sinergia calculada sobre la base de la Ecuación 1.

Ecuación 1 – Concentraciones inhibidoras fraccionarias (FIC)

Valores >0.5 muestra sinergia.

Al recompensar al examinador con placas fáciles de analizar, el método es algo laborioso y lento debido al cambio de tiras, así como la necesidad de usar dos placas por experimento. En su lugar, a menudo se emplea una prueba cruzada. En lugar de añadir las dos tiras de prueba E diferentes posteriormente una encima de la otra (después de la eliminación de la primera), ambas se colocan simultáneamente pero en forma de una cruz (ángulo de 90o), con los dos valores MIC previamente determinados formando el ángulo de 90o. Con este enfoque sólo se necesita una placa por prueba de sinergia, así como menos trabajo, por lo que es una opción preferida a pesar de ser un poco más difícil de analizar. Los nuevos valores MIC en el enfoque combinado de antibióticos se pueden visualizar como las zonas de inhibición modificadas, después de lo cual la sinergia puede ser determinada por la Ecuación 1.

de 90o), con los dos valores MIC previamente determinados formando el ángulo de 90o. Con este enfoque sólo se necesita una placa por prueba de sinergia, así como menos trabajo, por lo que es una opción preferida a pesar de ser un poco más difícil de analizar. Los nuevos valores MIC en el enfoque combinado de antibióticos se pueden visualizar como las zonas de inhibición modificadas, después de lo cual la sinergia puede ser determinada por la Ecuación 1.

En lugar de utilizar un enfoque de placa de agar, un enfoque de microcaldo a menudo puede ser preferencial debido a su mayor flexibilidad (por ejemplo, la capacidad de elegir concentraciones específicas de antibióticos fuera de los límites de una tira de prueba E). Además, se sugiere que las pruebas de microcaldeo son más sensibles debido a su distribución uniforme de antibióticos en una solución líquida, no dependiendo de la disociación dentro de una fase sólida (placa de agar). Los pozos en una microplaca de 96 pocillos serán inoculados con un número determinado de bacterias (106 cfu/ml: la concentración bacteriana se puede estimar mediante mediciones OD600 nm, estándares de turbidez o por muestras de chapado de propagación de diluciones seriales bacterianas 10x), y antibióticos en diferentes diluciones se añadirán a los pozos. Del mismo modo, a las tiras de prueba E MIC se determina como la intersección (pozo/ punto) con la concentración más baja de antibióticos que inhiben el crecimiento visible de bacterias.

Objetivo experimental

- El siguiente proyecto describe estrategias para determinar los valores MIC de la penicilina G y la gentamicina del grupo G de Streptococcus mediante dos métodos diferentes, la prueba electrónica y la microdilución. Para la prueba E, las placas de agar Mueller-Hinton inoculadas con Streptococcus grupo G se utilizaron en combinación con tiras de gradiente de penicilina G y/o gentamicina; mientras que el caldo MH con 50% de sangre de caballo lysed y 20 mg/ml-NAD se utilizaron con antibióticos solubles junto con Streptococcus grupo G en un enfoque de microcaldo.

Materiales

- Colonias bacterianas en una placa de agar en sangre, almacenadas <7 días en 4oC

- Placas de agar de sangre

- 0.5 Estándar McFarland

- 1% BacI2

- 1% H2SO4

- Tubo salino (2 mL)

- Aplicador con punta de algodón

- Placas de agar Mueller-Hinton (placas MHA)

- Caldo MH con 50% de sangre de caballo lysed y 20 mg/mL-NAD (MH-F)

- E-test penicilina/gentamicina (o antibióticos de interés) (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, Francia, Suecia)

- Antibióticos penicilina/gentamicina (o antibióticos de interés (polvo/solución))

Nota: Los medios específicos utilizados para el crecimiento bacteriano pueden variar para diferentes especies.

Procedure

Results

MIC values in E-test

Individual MIC values were identified in Figure 1 as 0.094 μg/mL for penicillin G and 8 μg/mLfor gentamicin. For synergy tests, both demonstrated an MIC value for penicillin G of 0.064 μg/mL (Figures 2, 3), while gentamicin had an MIC 4 μg/mL for cross and non-cross tests. Note a slight discrepancy between the cross and non-cross tests may occur due to the different incubation times of the strips in the two settings.

Calculation of synergy

The equation for FIC is:

= 1.18 >0.5 (no synergy)

= 1.18 >0.5 (no synergy)

MIC determination in broth

Cloudiness of the wells indicated bacterial growth, and thus no inhibition occurred. The first clear well with penicillin G (Figure 4) contained 0.12 μg/mL penicillin G, and hence this was the MIC value. For gentamicin the first clear well was present at 8 μg/mL gentamicin. The penicillin G value was slightly higher than when using an E-test, due to the higher resolution of the strip (e.g. based on a 1.5x factor serial dilution, not a 2x factor).

Inoculum size

To determine the inoculum size, an approach as outlined in Figure 5 and 6 was used. Colonies were counted in the D-row (1000x dilution), adding up to 7, 8, and 8 in the triplicate series with a mean value of 7.67 cfu. The number of colonies neeed to be multiplied with the dilution factor (e.g. 1000x), as well as with 100 to obtain cfu/mL, giving an inoculum size of approximately 8 x 105, well within the targeted inoculum size of 105-6 cfu/mL.

Applications and Summary

Antibiotic resistance is a worldwide health problem. In order to determine resistance mechanisms of microbes, methods testing for synergy and antagonism with different antibiotics is crucial. The E-test method is rapid, easy to replicate, and can be used to investigate any synergistic potential of combination therapies. The broth dilution method can also be assessed to predict bactericidal activity. In order to investigate the resistance mechanisms of different microbes, knowledge of synergistic and antagonistic antibiotic interactions is crucial. Combining antibiotics may be a strategy to increase treatment efficacy and face antibiotic resistance. In the tests performed here, we were able to determine the MIC values of penicillin G and gentamicin for group G Streptococcus. We also demonstrated that the two antibiotics do not display synergistic effects, thus would not be a preferred treatment option for such infections.

References

- Tan SY, Tatsumura Y. Alexander Fleming (1881-1955): Discoverer of penicillin. Singapore Medical Journal. 56 (7):366-7. (2015)

- Aminov RI. A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Frontiers in Microbiology. 1:134. (2010)

- Pankey GA, Ashcraft DS, Dornelles A. Comparison of 3 E-test (®) methods and time-kill assay for determination of antimicrobial synergy against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella species. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 77 (3):220-6. (2013)

- EUCAST: European Committee On Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (www.eucast.org).

- Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nature Protocols. 3 (2):163-75. (2008)

- Doern CD, When does 2 plus 2 equal 5? A review of antimicrobial synergy testing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52 (12):4124-28. (2014)

- Worthington RJ, Melander C. Combination approaches to combat multi-drug resistant bacteria. Trends in Biotechnology. 31 (3):177-84. (2013)

Transcript

Antibiotic susceptibility is defined as the sensitivity of a bacteria to antibiotics and can be measured using a broth dilution test or an Epsilometer test, also called an E-test.

In the broth dilution method, a standardized number of bacteria are added to a growth media containing serial antibiotic dilutions. If susceptible, the bacteria cannot grow at the higher antibiotic concentrations but continue to multiply at the lower antibiotic concentrations, causing media to turn turbid. The lowest antibiotic concentration at which the bacteria can no longer survive or multiply is referred to as the minimum inhibitory concentration, or MIC, value of the antibiotic for the given bacteria.

In an E-test, a plastic strip impregnated with a predefined gradient of antibiotic is applied over a freshly spread lawn of bacteria on a Mueller-Hinton agar, or MH-A, Petri plate. The antibiotic diffuses out into the agar media, where it is taken up by the bacteria. If susceptible, the bacteria cannot multiply and will die off, forming a clear zone around the E-strip, which is referred to as the growth inhibition zone. At the point where the growth intersects with the E-strip, the corresponding value on the scale gives the MIC value of the antibiotic.

Often antibiotics are used in combination to prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria. This often results in a synergistic, rather than additive, effect. Synergistic means that the combined effect of the two antibiotics is greater than the sum of their individual activities. However, the effect is considered significant only when the MIC value of the antibiotic combination decreases by at least two-fold. This criterion is evaluated by calculating the fractional inhibitory concentration, or FIC, index. By summing the ratio of the MIC of each antibiotic in combination with the MIC of each antibiotic individually, an FIC index less than 0.5 indicates synergy.

Antibiotic synergy can be measured using two E-test based methods: a non-cross test or a cross test. In a non-cross test, first, the E-strips for two different antibiotics with predetermined MIC values are applied to two separate plates. After the antibiotics have diffused into the medium, the original E-strips are removed and the E-strips for the alternate antibiotics are placed such that their MIC scales lay exactly over the MIC scales of the previous strips. In a cross test, which is a faster version of the non-cross test, the E-strips of the two antibiotics are placed together in a cross formation, such that the scales of their MIC marks form a 90 degree angle at the intersection. Following incubation in both techniques, the MIC value of each antibiotic in combination with the other antibiotic is read at the point where the growth inhibition zone intersects with the edge of the E-strip. Then, the FIC index is calculated.

This video will demonstrate how to determine the MIC value of a given antibiotic for a given bacteria using an E-test and a micro broth dilution test. You will also learn how to determine synergy between two antibiotics using a cross test and a non-cross test.

To begin, put on any appropriate personal protective equipment, including laboratory gloves and a lab coat. Next, sterilize the work space using 70% ethanol. Next, collect 15 milliliters of sterile Mueller-Hinton broth with 50% lysed horse blood and 20 milligrams per milliliter beta-nicotinamide. And five to eight Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Now, to prepare a McFarland turbidity standard number 0.5, measure out 9.95 milliliters of 1% sulfuric acid solution. Then, add 50 microliters of 1% barium chloride solution to the sulfuric acid solution. Vortex the solution well to obtain a turbid suspension. Cover the tube with aluminum foil and set it aside. Next, dispense one milliliter of saline solution into a 15 milliliter tube.

Use a sterile loop to scrape up a sample of the bacterial growth from your bacterial test plate, here, Streptococcus group G. Then, place the bacteria-laden loop into the saline solution, stir gently, and then vortex the tube well. Now, place the bacterial suspension and McFarland turbidity standards side by side and compare them for turbidity equivalence. Add either additional saline or bacterial colonies until the bacterial suspension’s turbidity matches that of the standard. Once the desired turbidity is obtained, dip a sterile cotton tip applicator into the bacterial suspension. To inoculate the MH-A plate, swab the entire surface of the plate gently with a zigzag motion. Next, label the bottom sides of the plates with the name of the bacteria and the date.

To begin, take out a penicillin G E-test strip, holding it by the edge with forceps. Gently place strip into the center of the freshly swabbed MH-A plate and replace the lid. In this example, a second antibiotic, gentamicin, is also tested. Thus, the strip placement process is repeated with the second plate and a gentamicin E-test strip. To determine the results of the E-test, collect the first plate that contains the penicillin G E-test strip. Now, determine the point where the inhibition zone intersects with the antibiotic strip. Read the corresponding numerical value on the scale. This value represents the MIC value of penicillin G. Determine the MIC value for gentamicin in the same manner.

To begin, inoculate an MH-A plate with Streptococcus group G strain bacteria. Label the bottom of the plate with the name of the bacteria, antibiotics to be used, and the date. Now, place an E-test strip for the antibiotic of interest in the center of the plate. Then, hold the second test strip at a 90 degree angle to the first strip and locate its MIC mark. Gently lay the second E-strip over the first at the point where the two MIC values intersect. Once the strips are placed, do not move them. Next, incubate the plates at 37 degrees celsius for 18 to 20 hours.

After inoculating two MH-A plates, with Streptococcus group G strain bacteria, place an E-test strip for one antibiotic on the surface of one plate. Then, place an E-test strip for the other antibiotic on the second plate as demonstrated. Using a plastic inoculation loop, mark the MIC value of each antibiotic on the surface of its respective plate. Next, cover the plates and incubate them at room temperature for one hour. After this, use forceps to remove the E strips. Next, collect one of the plates and an E-test strip for the other antibiotic. Hold the E-test strip over the imprint left by the first strip and locate the point where the MIC value on the E strip aligns with the marked line. Gently place the strip at this intersecting point. Repeat this process for the second plate and incubate both plates at 37 degrees celsius for 18 to 20 hours.

First, obtain a bacterial suspension with an established bacterial concentration and dilute the culture in MHF broth to achieve an OD600 of 0.003. Next, weigh out 16 milligrams of penicillin G and 128 milligrams of gentamicin. Transfer each weighed dry antibiotic into 215 milliliter conical tubes. Add 10 milliliters of distilled water to each of the conical tubes and mix well by vortexing. Label the tubes with the antibiotic name and concentration.

Performing the assay in triplicate, add 400 microliters of the working bacterial solution into the first wells of three rows of a 96-well microtiter plate. Next, add 200 microliters of the working bacterial solution in MHF broth to the wells of the three rows. Now, to generate a two-fold serial antibiotic dilution, first add four microliters of antibiotic stock to the first well, generating a 100 fold dilution. Sequentially, transfer 200 microliters of bacteria-antibiotic solution to each well, beginning from the first well through the second to last well in each row, ensure proper mixing by pipetting two to three times after every transfer. Discard the final 200 microliters of bacteria-antibiotic solution.

To determine the results of the broth micro dilution test for penicillin G, first locate the wells that exhibit no visible bacterial growth, indicated by a lack of turbidity. From these wells, identify the well with the lowest antibiotic concentration. This represents the MIC value of penicillin G for the tested bacteria. The MIC value of gentamicin can be determined using the same assay and technique.

To determine the results of the non-cross test, collect the first plate, which contains a penicillin G E strip. Then, determine the point where the growth inhibition zone intersects with the antibiotic strip. The corresponding value on the scale represents the MIC value for penicillin G in combination with gentamicin. In this example, the MIC value in combination is 0.064 micrograms per milliliter.

Now, collect the second plate, which contains the gentamicin E strip, and determine the MIC value in combination as previously demonstrated. To evaluate the effect of combination, first calculate the fractional inhibitory concentration or FIC for penicillin G by dividing the MIC in combination by the MIC of the antibiotic alone. Repeat this process for gentamicin. Then, calculate the FIC index using the equation shown here. A two-fold reduction in the MIC value in combination yields an FIC index value that is less than or equal to 0.5 and demonstrates synergy between penicillin G and gentamicin. In this case, the calculated FIC value is 1.18 which is greater than 0.5. Thus, the results do not demonstrate synergy between penicillin G and gentamicin against the Streptococcus group G strain.

To determine the results of the cross test, first determine the point where the growth inhibition zones intersect with their respective E strips. Read the numerical value on each E-test strip that corresponds to this intersection point. These values represent the MIC value in combination for penicillin G and gentamicin. Next, to evaluate the effect of the combination, calculate the FIC index using the equation shown here. In this example, the calculated FIC value is 1.18, which is greater than 0.5. This means that penicillin G and gentamicin do not act synergistically against the Streptococcus group G strain.