Microscopie et coloration : Gram, Capsule et endospores.

English

Share

Overview

Source: Rhiannon M. LeVeque1, Natalia Martin1, Andrew J. Van Alst1, et Victor J. DiRita1

1 Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, États-Unis d’Amérique

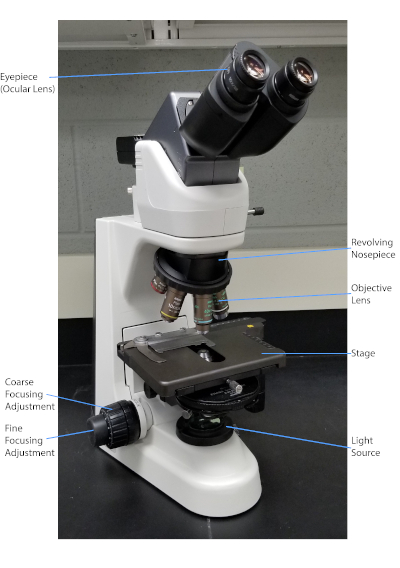

Les bactéries sont diverses micro-organismes que l’on trouve presque partout sur Terre. De nombreuses propriétés aident à les distinguer les unes des autres, y compris, mais sans s’y limiter, le type, la forme et l’arrangement de Gram, la production de capsules et la formation de spores. Pour observer ces propriétés, on peut utiliser la microscopie légère; cependant, certaines caractéristiques bactériennes (par exemple la taille, le manque de coloration et les propriétés réfractives) font qu’il est difficile de distinguer les bactéries uniquement avec un microscope léger (1, 2). La coloration des bactéries est nécessaire pour distinguer les types bactériens par microscopie légère. Les deux principaux types de microscopes légers sont simples et composés. La principale différence entre eux est le nombre de lentilles utilisées pour amplifier l’objet. Les microscopes simples (par exemple une loupe) n’ont qu’une lentille pour grossir un objet, tandis que les microscopes composés ont plusieurs lentilles pour améliorer le grossissement (figure 1). Les microscopes composés ont une lentille objective près de l’objet qui recueille la lumière pour créer une image de l’objet. Ceci est ensuite amplifié par l’oculaire (lentille oculaire) qui agrandit l’image. La combinaison de la lentille objective et de l’oculaire permet un grossissement plus élevé que l’utilisation d’une seule lentille. Typiquement, les microscopes composés ont plusieurs lentilles objectives de différents pouvoirs pour permettre un grossissement différent (1, 2). Ici, nous discuterons de la visualisation des bactéries avec des taches Gram, taches Capsule, et les taches Endospore.

Figure 1 : Microscope composé typique. Les parties les plus importantes du microscope sont étiquetées.

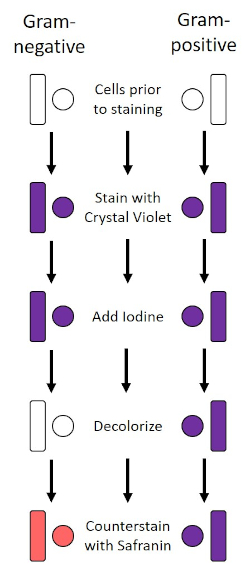

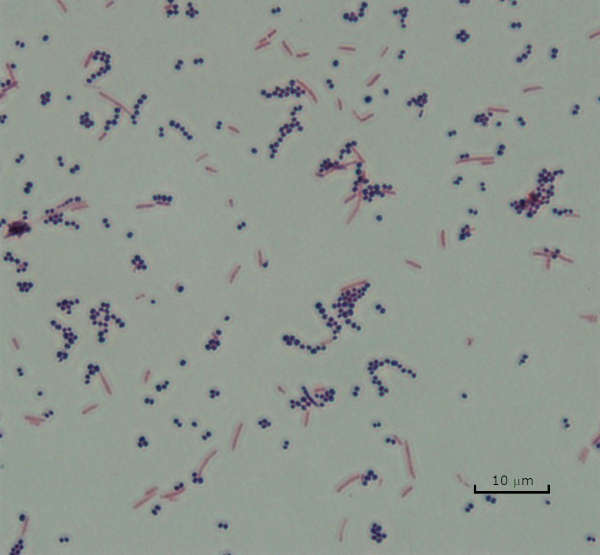

La tache Gram, développée en 1884 par le bactériologiste danois Hans Christian Gram (1), différencie les bactéries en fonction de la composition de la paroi cellulaire (1, 2, 3, 4). En bref, un frottis bactérien est placé sur une lame de microscope, puis fixé à la chaleur pour adhérer les cellules à la diapositive et les rendre plus facilement accepter des taches (1). L’échantillon fixé à la chaleur est taché de Violet de Cristal, transformant les cellules pourpres. La glissière est rincée avec une solution d’iode, qui fixe le Violet de Cristal à la paroi cellulaire, suivie d’un décoloreur (un alcool) pour laver toute violet de cristal non fixe. Dans la dernière étape, une contre-tache, Safranin, est ajoutée aux cellules de couleur rouge (figure 2). Les bactéries Gram-positives tachent le pourpre en raison de la couche épaisse de peptidoglycan qui n’est pas facilement pénétrée par le décoloreur ; Les bactéries Gram-négatives, avec leur couche peptidoglycan plus mince et leur teneur en lipides plus élevée, se décolorent avec le décolorant et sont contre-tachées en rouge lors de l’ajout de Safranin (figure 3). La coloration Gram est utilisée pour différencier les cellules en deux types (Gram-positif et Gram-négatif) et est également utile pour distinguer la forme cellulaire (sphères ou cocci, tiges, tiges courbes et spirales) et l’arrangement (cellules simples, paires, chaînes, groupes et clusters) (1, 3) .

Figure 2 : Schéma du protocole de coloration de gram. La colonne de gauche montre comment les bactéries Gram-négatives réagissent à chaque étape du protocole. La colonne de droite montre comment les bactéries Gram-positives réagissent. On y voit également deux formes de cellules bactériennes typiques : les bacilles (ou tiges) et les cocci (ou sphères).

Figure 3 : Résultats de la coloration de Gram. Une tache de Gram d’un mélange de Staphylococcus aureus (Cocci pourpre Gram-positif) et Escherichia coli (gram-négatifs tiges rouges).

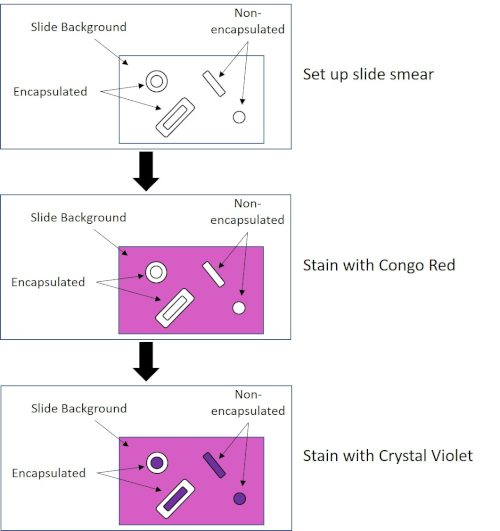

Certaines bactéries produisent une couche externe visqueuse extracellulaire appelée capsule (3, 5). Les capsules sont des structures protectrices avec diverses fonctions, y compris mais sans s’y limiter à l’adhérence aux surfaces et à d’autres bactéries, à la protection contre la dessiccation et à la protection contre la phagocytose. Les capsules sont généralement composées de polysaccharides contenant plus de 95 % d’eau, mais certaines peuvent contenir des polyalcools et des polyamines (5). En raison de leur composition la plupart du temps non-ionique et de la tendance à repousser des taches, les méthodes simples de coloration ne fonctionnent pas avec la capsule ; au lieu de cela, la coloration de capsule utilise une technique négative de coloration qui tache les cellules et l’arrière-plan, laissant la capsule comme halo clair autour des cellules (1, 3) (figure 4). La coloration de capsule implique le barbouillage d’un échantillon bactérien dans une tache acide sur une glissière de microscope. Contrairement à la coloration Gram, le frottis bactérien n’est pas fixé à la chaleur lors d’une tache capsule. La fixation de la chaleur peut perturber ou déshydrater la capsule, ce qui entraîne de faux négatifs (5). En outre, la fixation de la chaleur peut rétrécir les cellules résultant en une compensation autour de la cellule qui peut être confondue comme une capsule, conduisant à de faux positifs (3). La tache acide colore le fond de diapositive ; tout en faisant un suivi avec une tache de base, Crystal Violet, colore les cellules bactériennes elles-mêmes, laissant la capsule intacte et apparaissant comme un halo clair entre les cellules et le fond de diapositive (figure 5). Traditionnellement, l’encre de L’Inde a été utilisée comme tache acide parce que ces particules ne peuvent pas pénétrer dans la capsule. Par conséquent, ni la capsule ni la cellule n’est souillée par l’encre de l’Inde; au lieu de cela, l’arrière-plan est taché. Congo Rouge, Nigrosin, ou Eosin peut être utilisé à la place de l’encre de l’Inde. La coloration des capsules peut aider les médecins à diagnostiquer les infections bactériennes lorsqu’ils examinent les cultures à partir d’échantillons de patients et à orienter le traitement approprié des patients. Les maladies courantes causées par les bactéries encapsulées comprennent la pneumonie, la méningite et la salmonellose.

Figure 4 : Schéma du protocole de coloration des capsules. Le panneau supérieur affiche le frottis de diapositive avant toute application de tache. Le panneau du milieu montre comment la diapositive et les bactéries s’occupent de la tache primaire, Congo Red. Le panneau final montre comment la diapositive et les bactéries s’occupent de la contre-tache, Crystal Violet.

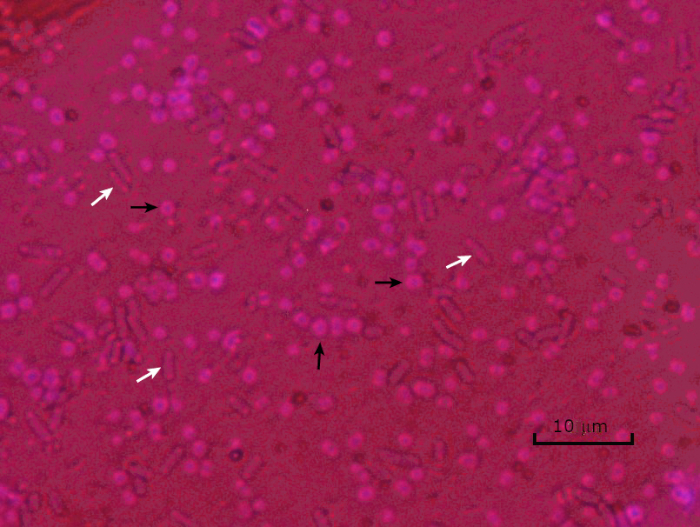

Figure 5 : Résultats de la coloration des capsules. Coloration capsule d’Acinetobacter baumannii encapsulé (dénoté avec des flèches noires) et d’Escherichia coli non encapsulé (dénoté avec des flèches blanches). Notez que l’arrière-plan est sombre et que les cellules A. baumannii sont tachées de pourpre. La capsule autour des cellules A. baumannii est évidente comme un halo, tandis que E. coli n’a pas de halo.

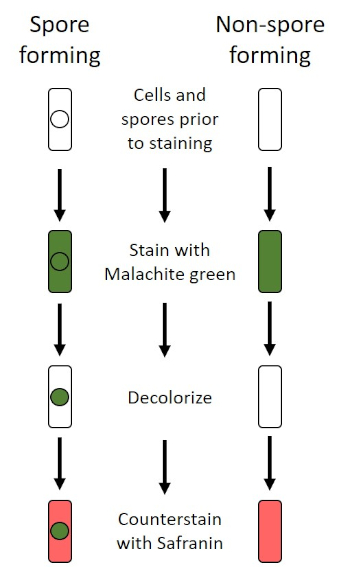

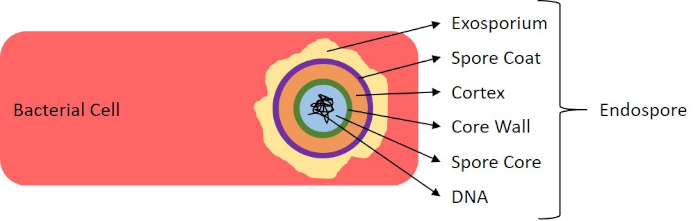

Dans des conditions défavorables (par exemple limitation des nutriments, températures extrêmes ou déshydratation), certaines bactéries produisent des endospores, des structures métaboliquement inactives qui résistent aux dommages physiques et chimiques (1, 2, 8, 9). Les endospores permettent à la bactérie de survivre à des conditions difficiles en protégeant le matériel génétique des cellules; une fois que les conditions sont favorables à la croissance, les spores germent et la croissance bactérienne continue. Les endospores sont difficiles à tacher avec des techniques de coloration standard parce qu’elles sont imperméables aux colorants généralement utilisés pour la coloration (1, 9). La technique couramment utilisée pour tacher les endospores est la méthode Schaeffer-Fulton (figure 6), qui utilise la tache primaire Malachite Green, une tache soluble dans l’eau qui se lie relativement faiblement au matériel cellulaire, et la chaleur, pour permettre à la tache de se briser à travers le cortex de la spore (figure 7). Ces étapes colorent les cellules de plus en plus (appelées cellules végétatives dans le contexte de la biologie de l’endospore), ainsi que les endospores et les spores libres (celles qui ne se trouvent plus dans l’ancienne enveloppe cellulaire). Les cellules végétatives sont lavées à l’eau pour enlever Malachite Green; les endospores conservent la tache due au chauffage du vert de Malachite dans la spore. Enfin, les cellules végétatives sont contre-tachées avec Safranin pour visualiser (figure 8). La coloration des endospores aide à différencier les bactéries en anciens spores et en anciens non-spore, ainsi qu’à déterminer si les spores sont présentes dans un échantillon qui, s’il est présent, pourrait entraîner une contamination bactérienne lors de la germination.

Figure 6 : Schéma du Protocole de coloration endospore. La colonne de gauche montre comment les bactéries formant des spores réagissent à chaque étape du protocole. La colonne de droite montre comment les bactéries qui ne forment pas les spores réagissent.

Figure 7 : Diagramme de la structure d’Endospore. Cellule bactérienne contenant un endospore avec les diverses structures de spores étiquetées.

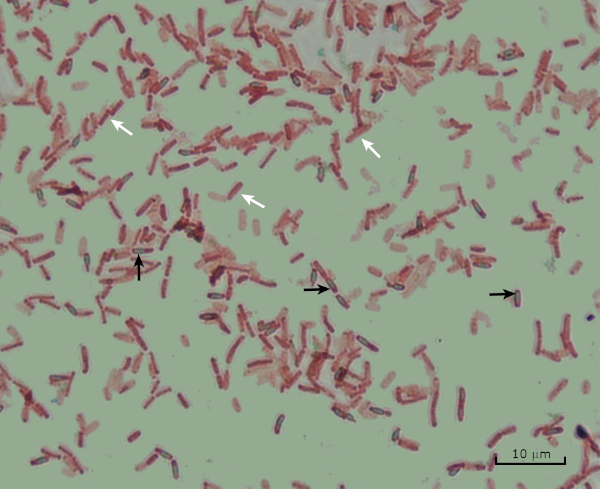

Figure 8 : Résultats de la coloration des endospores. Une coloration typique des endospores de Bacillus subtilis. Les cellules végétatives (démarquées par les flèches blanches) sont tachées de rouge, tandis que les endospores (dénotées avec les flèches noires) sont teintées de vert.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Bacteria have distinguishing characteristics that can aid in their identification. Some of these characteristics can be observed by staining and light microscopy. Three staining techniques useful for observing these characteristics are Gram staining, Capsule staining, and Endospore staining. Each technique identifies different characteristics of bacteria and can be used to help physicians recommend treatments for patients, identify potential contaminants in samples or food products, and verify sample sterility.

References

- Black, J. G. Microbiology Principles and Explorations, 4th edition. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (1999)

- Madigan, M. T. and J. M. Martinko. Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 11th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (2006).

- Leboffe, M. J., and B. E. Pierce. A Photographic Atlas for the Microbiology Laboratory, 2nd ed. Morton Publishing Company, Englewood, Colorado. (1996).

- Smith, A. C. and M. A. Hussey. Gram stain protocols. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.2886. (2005).

- Hughes, R. B. and A. C. Smith. Capsule Stain Protocols Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3041. (2007).

- Anthony, E. E. Jr. A note on capsule staining. Science 73(1890):319-320 (1931).

- Finegold, S. M., W. J. Martin, and E. G. Scott. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology, 5th edition. The C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Missouri. (1978).

- Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. (1994).

- Hussey, M. A. and A. Zayaitz. Endospore Stain Protocol. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3112. (2007).

Transcript

Bacteria are microscopic living organisms that have many distinguishing characteristics such as shape, arrangement of cells, whether or not they produce capsules, and if they form spores. These features can all be visualized by staining and aid in the identification and classification of different bacterial species.

To examine the first two characteristics of cell shape and arrangement, we can use a simple technique called Gram staining. Here, crystal violet is applied to bacteria, which have been heat-fixed onto a slide. Next, Gram’s iodine solution is added to the slide, resulting in the formation of an insoluble complex between the crystal violet and the Gram’s iodine solution. A decolorizer is then applied and any bacteria with a thick peptidoglycan layer will stain purple, as this layer is not easily penetrated by the decolorizer. These bacteria are referred to as Gram-positive.

Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer and will de-stain the decolorizer, losing the purple color. However, they will stain reddish-pink when a safranin counterstain is added, which binds to a lipopolysaccharide layer on their outside. Once stained, the cells can be observed for morphology, size, and arrangement, such as in chains or clusters, which further aids in classification and identification.

Another useful technique in the microbiologist’s toolkit is the capsule stain, used to visualize external capsules that surround some types of bacterial cells. Due to the capsule’s non-ionic composition and tendency to repel stains, simple staining methods won’t work. Instead, a negative staining technique is used, which first stains the background with an acidic colorant, such as Congo red, before the bacterial cells are stained with crystal violet. This leaves any capsule present as a clear halo around the cells.

The final major staining technique covered here can help determine if the bacteria being studied forms spores. In adverse conditions, some bacteria produce endospores, dormant, tough, non-reproductive structures whose primary function is to ensure the survival of bacteria through periods of environmental stress, like extreme temperatures or dehydration. However, not all bacterial species make endospores, and they are difficult to stain with standard techniques because they are impermeable to many dyes. The Schaeffer-Fulton method uses malachite green stain, which is applied to the bacteria fixed to a slide. The slide is then washed with water before being counterstained with Safranin. Vegetative cells will appear pinkish-red, while any endospores present will appear green. In this video, you will learn how to perform these common bacterial staining techniques and then examine the staining samples using light microscopy.

To begin the procedure, tie back long hair and put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves.

Then, clean a fresh microscope slide with a laboratory wipe. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X phosphate-buffered saline onto the first slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacterial colony in the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry.

Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Using tongs, pass the slide through the burner flame several times, with the bacteria side up, taking care not to hold the slide in the flame too long, which may distort the cells.

Now, working over the sink, hold the slide level and apply several drops of Gram’s crystal violet to completely cover the bacterial smear and then place the slide onto the bench to stand for 45 seconds. Next, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacterial smear directly. Now, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s iodine solution to completely cover the stained bacteria and then allow it to stand for another 45 seconds. Next, carefully rinse the iodine from the slide, as shown previously. While holding the slide at an angle, add a few drops of Gram’s decolorizer to the slide, allowing it to run down over the stained bacteria, just until the run-off is clear, for approximately 5 seconds. Immediately, rinse with water as shown previously. This will limit over-decolorizing the smear. Next, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s safranin counterstain to completely cover the stained bacteria. After 45 seconds, gently rinse the Safranin from the slide with water, as shown previously, and then blot dry with paper towels.

Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective lens.

To begin this staining protocol, first put on the correct personal protective equipment and then ensure that the glass slides that will be used are clean.

Next, prepare the solutions. To make 1% crystal violet solution, mix 0.25 grams of crystal violet powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Then, prepare 1% Congo red solution by mixing 0.25 grams of Congo red powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Now, pipette 10 microliters of the Congo red solution onto the slide. Using a clean, sterile pipette tip, select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Then, smear the bacterial colony into the dye to produce a thin, even layer. Completely air dry the bacterial slide for 5-7 minutes. Once the slide is dry, flood the smear with enough 1% crystal violet to cover the smear and let it sit for 1 minute. Now, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacteria directly. Continue holding the slide at a 45-degree angle until completely air-dried. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective.

To perform endospore staining, first, prepare a 0.5% malachite green solution by mixing 0. 125 grams of malachite green powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water, and then vortex the solution until dissolved. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X PBS onto the center of the slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacteria into the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Now, set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry. Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Pass the slide through the blue burner flame several times, with the bacteria side facing up. Then, once the slide has cooled, place a piece of precut lens paper over the heat-fixed smear. Next, turn on a hotplate to the highest setting, and bring a beaker of water to a boil.

Saturate the lens paper with the malachite green solution and, using tongs, place the slide on top of the beaker of boiling water to steam for 5 minutes. Keep the lens paper moist by adding more dye, one drop at a time, as needed. Next, again using tongs, pick up the slide from the beaker and remove and discard the lens paper. Allow the slide to cool for 2 minutes. Working over the sink, hold the slide at an angle, and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide. Now, hold the slide level and apply Safranin to completely cover the slide. Then, allow it to stand for 1 minute. Next, hold the slide at an angle and rinse as previously shown. Allow the slide to air dry on the benchtop. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide with a light microscope, with a 100X oil objective.

In the Gram staining protocol, two different colored stains can result. Dark purple staining indicates that the bacteria are Gram-positive and that they have retained the crystal violet stain. In contrast, reddish-pink staining is a characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria, which instead will be colored by the Safranin counterstain. Additionally, different shapes and arrangements of bacteria can be visualized after Gram staining. For example, it is possible to differentiate Cocci, or round bacteria, from rod-shaped Bacillus, or identify bacteria, which forms strands, compared to those which typically aggregate as clumps or occur singly.

In a capsule stained microscope image, the bacterial cells will typically be stained purple, and the background of the slide should be darkly stained. Against this dark background, the capsules of the bacteria, if present, will appear as a clear halo around the cells.

Lastly, in endospore staining, Vegetative cells will be stained red by the Safranin counterstain. If endospores are present in the sample, these will retain the malachite green stain and appear bluish-green in color.