Microscopia e colorazioni: la colorazione di Gram, delle endospore e del capside

English

Share

Overview

Fonte: Rhiannon M. LeVeque1, Natalia Martin1, Andrew J. Van Alst1e Victor J. DiRita1

1 Dipartimento di Microbiologia e Genetica Molecolare, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, Stati Uniti d’America

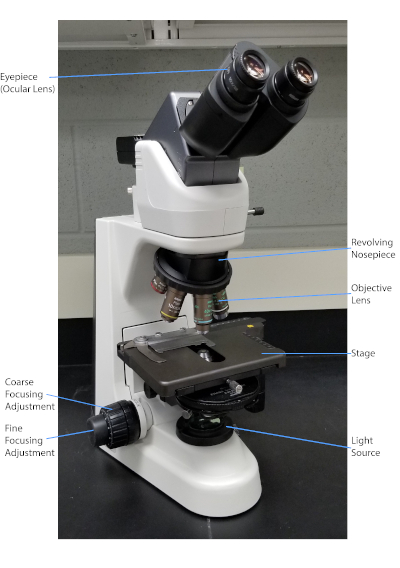

I batteri sono diversi microrganismi che si trovano quasi ovunque sulla Terra. Molte proprietà aiutano a distinguerli l’uno dall’altro, incluso ma non limitato al tipo di colorazione di Gram, alla forma e alla disposizione, alla produzione di capsule e alla formazione di spore. Per osservare queste proprietà, si può usare la microscopia ottica; tuttavia, alcune caratteristiche batteriche (ad esempio dimensioni, mancanza di colorazione e proprietà di rifrazione) rendono difficile distinguere i batteri esclusivamente con un microscopio ottico (1, 2). La colorazione dei batteri è necessaria quando si distinguono i tipi batterici con la microscopia ottica. I due principali tipi di microscopi otscopici sono semplici e composti. La principale differenza tra loro è il numero di lenti utilizzate per ingrandire l’oggetto. I microscopi semplici (ad esempio una lente d’ingrandimento) hanno una sola lente per ingrandire un oggetto, mentre i microscopi composti hanno diverse lenti per migliorare l’ingrandimento (Figura 1). I microscopi composti hanno una lente obiettiva vicino all’oggetto che raccoglie la luce per creare un’immagine dell’oggetto. Questo viene poi ingrandito dall’oculare (lente oculare) che ingrandisce l’immagine. La combinazione dell’obiettivo e dell’oculare consente un ingrandimento maggiore rispetto all’utilizzo di una singola lente da sola. Tipicamente, i microscopi composti hanno più lenti obiettivo di varie potenze per consentire un ingrandimento diverso (1, 2). Qui, discuteremo la visualizzazione dei batteri con macchie di Gram, macchie di capsule e macchie di endospore.

Figura 1: Un tipico microscopio composto. Le parti più importanti del microscopio sono etichettate.

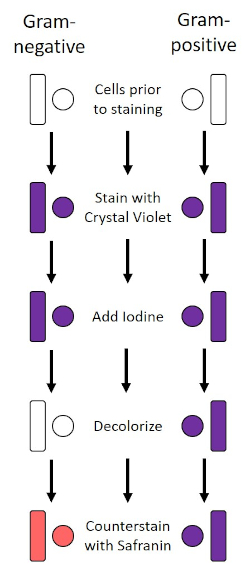

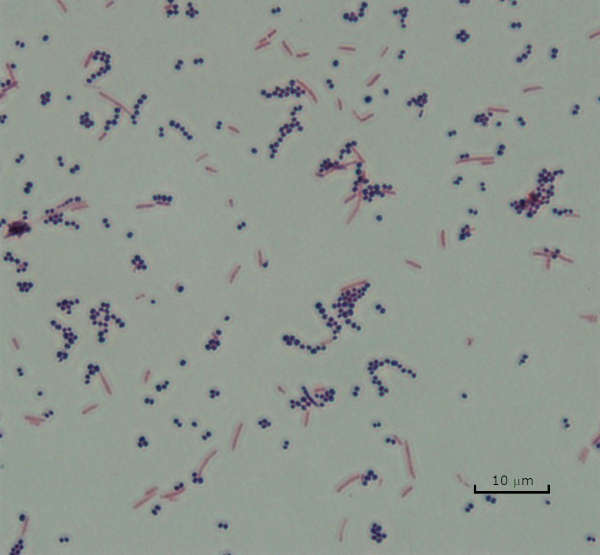

La macchia di Gram, sviluppata nel 1884 dal batteriologo danese Hans Christian Gram (1), differenzia i batteri in base alla composizione della parete cellulare (1, 2, 3, 4). In breve, uno striscio batterico viene posto su un vetrino per microscopio e quindi fissato a calore per far aderire le cellule al vetrino e renderle più facilmente accettabili delle macchie (1). Il campione fissato a caldo viene colorato con Crystal Violet, trasformando le cellule in viola. Il vetrino viene lavato con una soluzione di iodio, che fissa il Crystal Violet alla parete cellulare, seguito da un decolorante (un alcool) per lavare via qualsiasi Crystal Violet non fisso. Nella fase finale, una controcolore, Safranin, viene aggiunta alle celle colorate di rosso (Figura 2). I batteri Gram-positivi si colorano di viola a causa dello spesso strato di peptidoglicano che non è facilmente penetrato dal decolorante; I batteri Gram-negativi, con il loro strato peptidoglicano più sottile e il più alto contenuto lipidico, si dissacrono con il decolorante e sono controcolorati di rosso quando viene aggiunta Safranina (Figura 3). La colorazione di Gram viene utilizzata per differenziare le cellule in due tipi (Gram-positivo e Gram-negativo) ed è anche utile per distinguere la forma delle cellule (sfere o cocchi, aste, aste curve e spirali) e la disposizione (celle singole, coppie, catene, gruppi e cluster) (1, 3).

Figura 2: Schema del protocollo di colorazione di Gram. La colonna di sinistra mostra come reagiscono i batteri Gram-negativi in ogni fase del protocollo. La colonna di destra mostra come reagiscono i batteri Gram-positivi. Inoltre, sono mostrate due tipiche forme di cellule batteriche: i bacilli (o bastoncelli) e i cocchi (o sfere).

Figura 3: Risultati della colorazione di Gram. Una macchia di Gram di una miscela di Staphylococcus aureus (cocchi viola Gram-positivi) ed Escherichia coli (barre rosse Gram-negative).

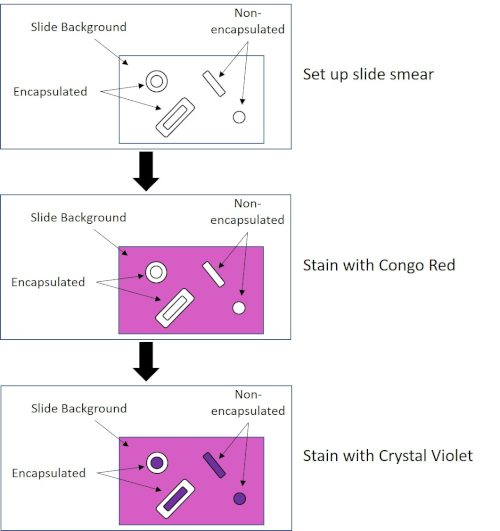

Alcuni batteri producono uno strato esterno viscoso extracellulare chiamato capsula (3, 5). Le capsule sono strutture protettive con varie funzioni, tra cui, a titolo esemplificativo ma non esaustivo, l’aderenza a superfici e altri batteri, la protezione dall’essiccazione e la protezione dalla fagocitosi. Le capsule sono tipicamente composte da polisaccaridi contenenti più del 95% di acqua, ma alcune possono contenere polialcoli e poliammine (5). A causa della loro composizione per lo più non ionica e della tendenza a respingere le macchie, i semplici metodi di colorazione non funzionano con la capsula; invece, la colorazione della capsula utilizza una tecnica di colorazione negativa che macchia le cellule e lo sfondo, lasciando la capsula come un alone chiaro intorno alle cellule (1, 3) (Figura 4). La colorazione della capsula comporta la spalma di un campione batterico in una macchia acida su un vetrino per microscopio. A differenza della colorazione di Gram, lo striscio batterico non viene fissato termicamente durante una colorazione della capsula. Il fissaggio del calore può interrompere o disidratare la capsula, portando a falsi negativi (5). Inoltre, il fissaggio termico può ridurre le celle con conseguente pulizia intorno alla cellula che può essere scambiata per una capsula, portando a falsi positivi (3). La macchia acida colora lo sfondo della diapositiva; mentre segue con una macchia di base, Crystal Violet, colora le cellule batteriche stesse, lasciando la capsula incontaminata e apparendo come un alone chiaro tra le cellule e lo sfondo del vetrino (Figura 5). Tradizionalmente, l’inchiostro indiano è stato usato come macchia acida perché queste particelle non possono penetrare nella capsula. Pertanto, né la capsula né la cellula sono macchiate dall’inchiostro dell’India; invece, lo sfondo è macchiato. Congo Red, Nigrosin o Eosin possono essere utilizzati al posto dell’inchiostro indiano. La colorazione della capsula può aiutare i medici a diagnosticare le infezioni batteriche quando si guardano le colture dai campioni dei pazienti e guidare il trattamento appropriato del paziente. Le malattie comuni causate da batteri incapsulati includono polmonite, meningite e salmonellosi.

Figura 4: Schema del protocollo di colorazione della capsula. Il pannello superiore mostra lo striscio di scorrimento prima di qualsiasi applicazione di macchia. Il pannello centrale mostra come la diapositiva e i batteri si occupano della macchia primaria, Congo Red. Il pannello finale mostra come il vetrino e i batteri si occupano della controcolorazione, Crystal Violet.

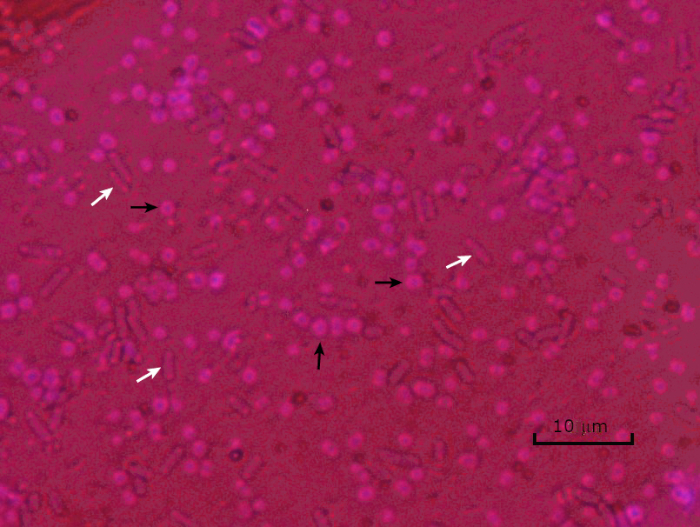

Figura 5: Risultati della colorazione della capsula. Colorazione della capsula di Acinetobacter baumannii incapsulato (indicato con frecce nere) e Escherichia coli non incapsulato (indicato con frecce bianche). Si noti che lo sfondo è scuro e le cellule di A. baumannii sono macchiate di viola. La capsula intorno alle cellule di A. baumannii è evidente come un alone, mentre E. coli non ha alone.

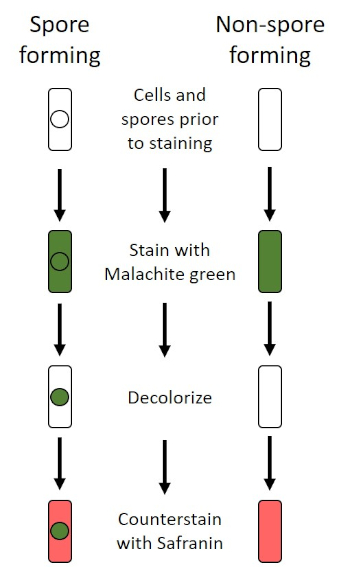

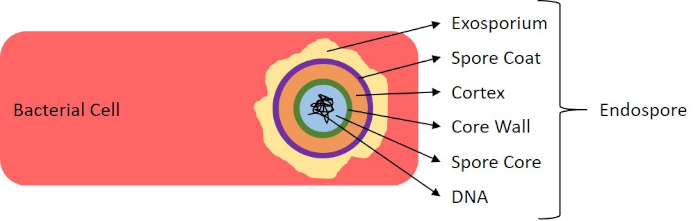

In condizioni avverse (ad esempio limitazione dei nutrienti, temperature estreme o disidratazione), alcuni batteri producono endospore, strutture metabolicamente inattive resistenti ai danni fisici e chimici (1, 2, 8, 9). Le endospore consentono al batterio di sopravvivere a condizioni difficili proteggendo il materiale genetico delle cellule; una volta che le condizioni sono favorevoli alla crescita, le spore germinano e la crescita batterica continua. Le endospore sono difficili da macchiare con le tecniche di colorazione standard perché sono impermeabili ai coloranti tipicamente utilizzati per la colorazione (1, 9). La tecnica abitualmente utilizzata per macchiare le endospore è il Metodo Schaeffer-Fulton (Figura 6),che utilizza la macchia primaria Malachite Green, una macchia solubile in acqua che si lega relativamente debolmente al materiale cellulare, e il calore, per consentire alla macchia di sfondare la corteccia della spora (Figura 7). Questi passaggi colorano le cellule in crescita (denominate cellule vegetative nel contesto della biologia delle endospore), così come le endospore e le eventuali spore libere (quelle che non sono più all’interno del precedente involucro cellulare). Le cellule vegetative vengono lavate con acqua per rimuovere Malachite Green; le endospore trattengono la macchia a causa del riscaldamento del verde malachite all’interno della spora. Infine, le cellule vegetative sono controbattete con Safranin per visualizzare (Figura 8). La colorazione per le endospore aiuta a differenziare i batteri in formatori di spore e formatori non sporici, oltre a determinare se le spore sono presenti in un campione che, se presente, potrebbe portare a contaminazione batterica al momento della germinazione.

Figura 6: Schema del protocollo di colorazione delle endospore. La colonna di sinistra mostra come reagiscono i batteri che formano spore in ogni fase del protocollo. La colonna di destra mostra come reagiscono i batteri che non formano spore.

Figura 7: Diagramma della struttura delle endospore. Cellula batterica contenente un’endospora con le varie strutture sporiche etichettate.

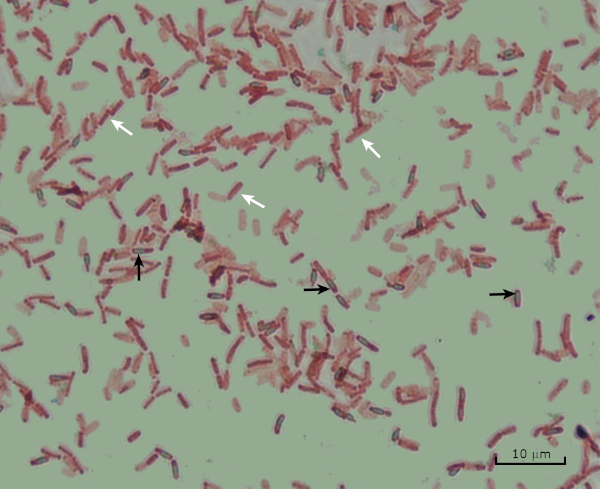

Figura 8: Risultati della colorazione delle endospore. Una colorazione tipica delle endospore di Bacillus subtilis. Le cellule vegetative (indicate con le frecce bianche) sono macchiate di rosso, mentre le endospore (denotate con le frecce nere) sono macchiate di verde.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Bacteria have distinguishing characteristics that can aid in their identification. Some of these characteristics can be observed by staining and light microscopy. Three staining techniques useful for observing these characteristics are Gram staining, Capsule staining, and Endospore staining. Each technique identifies different characteristics of bacteria and can be used to help physicians recommend treatments for patients, identify potential contaminants in samples or food products, and verify sample sterility.

References

- Black, J. G. Microbiology Principles and Explorations, 4th edition. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (1999)

- Madigan, M. T. and J. M. Martinko. Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 11th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (2006).

- Leboffe, M. J., and B. E. Pierce. A Photographic Atlas for the Microbiology Laboratory, 2nd ed. Morton Publishing Company, Englewood, Colorado. (1996).

- Smith, A. C. and M. A. Hussey. Gram stain protocols. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.2886. (2005).

- Hughes, R. B. and A. C. Smith. Capsule Stain Protocols Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3041. (2007).

- Anthony, E. E. Jr. A note on capsule staining. Science 73(1890):319-320 (1931).

- Finegold, S. M., W. J. Martin, and E. G. Scott. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology, 5th edition. The C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Missouri. (1978).

- Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. (1994).

- Hussey, M. A. and A. Zayaitz. Endospore Stain Protocol. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3112. (2007).

Transcript

Bacteria are microscopic living organisms that have many distinguishing characteristics such as shape, arrangement of cells, whether or not they produce capsules, and if they form spores. These features can all be visualized by staining and aid in the identification and classification of different bacterial species.

To examine the first two characteristics of cell shape and arrangement, we can use a simple technique called Gram staining. Here, crystal violet is applied to bacteria, which have been heat-fixed onto a slide. Next, Gram’s iodine solution is added to the slide, resulting in the formation of an insoluble complex between the crystal violet and the Gram’s iodine solution. A decolorizer is then applied and any bacteria with a thick peptidoglycan layer will stain purple, as this layer is not easily penetrated by the decolorizer. These bacteria are referred to as Gram-positive.

Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer and will de-stain the decolorizer, losing the purple color. However, they will stain reddish-pink when a safranin counterstain is added, which binds to a lipopolysaccharide layer on their outside. Once stained, the cells can be observed for morphology, size, and arrangement, such as in chains or clusters, which further aids in classification and identification.

Another useful technique in the microbiologist’s toolkit is the capsule stain, used to visualize external capsules that surround some types of bacterial cells. Due to the capsule’s non-ionic composition and tendency to repel stains, simple staining methods won’t work. Instead, a negative staining technique is used, which first stains the background with an acidic colorant, such as Congo red, before the bacterial cells are stained with crystal violet. This leaves any capsule present as a clear halo around the cells.

The final major staining technique covered here can help determine if the bacteria being studied forms spores. In adverse conditions, some bacteria produce endospores, dormant, tough, non-reproductive structures whose primary function is to ensure the survival of bacteria through periods of environmental stress, like extreme temperatures or dehydration. However, not all bacterial species make endospores, and they are difficult to stain with standard techniques because they are impermeable to many dyes. The Schaeffer-Fulton method uses malachite green stain, which is applied to the bacteria fixed to a slide. The slide is then washed with water before being counterstained with Safranin. Vegetative cells will appear pinkish-red, while any endospores present will appear green. In this video, you will learn how to perform these common bacterial staining techniques and then examine the staining samples using light microscopy.

To begin the procedure, tie back long hair and put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves.

Then, clean a fresh microscope slide with a laboratory wipe. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X phosphate-buffered saline onto the first slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacterial colony in the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry.

Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Using tongs, pass the slide through the burner flame several times, with the bacteria side up, taking care not to hold the slide in the flame too long, which may distort the cells.

Now, working over the sink, hold the slide level and apply several drops of Gram’s crystal violet to completely cover the bacterial smear and then place the slide onto the bench to stand for 45 seconds. Next, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacterial smear directly. Now, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s iodine solution to completely cover the stained bacteria and then allow it to stand for another 45 seconds. Next, carefully rinse the iodine from the slide, as shown previously. While holding the slide at an angle, add a few drops of Gram’s decolorizer to the slide, allowing it to run down over the stained bacteria, just until the run-off is clear, for approximately 5 seconds. Immediately, rinse with water as shown previously. This will limit over-decolorizing the smear. Next, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s safranin counterstain to completely cover the stained bacteria. After 45 seconds, gently rinse the Safranin from the slide with water, as shown previously, and then blot dry with paper towels.

Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective lens.

To begin this staining protocol, first put on the correct personal protective equipment and then ensure that the glass slides that will be used are clean.

Next, prepare the solutions. To make 1% crystal violet solution, mix 0.25 grams of crystal violet powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Then, prepare 1% Congo red solution by mixing 0.25 grams of Congo red powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Now, pipette 10 microliters of the Congo red solution onto the slide. Using a clean, sterile pipette tip, select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Then, smear the bacterial colony into the dye to produce a thin, even layer. Completely air dry the bacterial slide for 5-7 minutes. Once the slide is dry, flood the smear with enough 1% crystal violet to cover the smear and let it sit for 1 minute. Now, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacteria directly. Continue holding the slide at a 45-degree angle until completely air-dried. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective.

To perform endospore staining, first, prepare a 0.5% malachite green solution by mixing 0. 125 grams of malachite green powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water, and then vortex the solution until dissolved. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X PBS onto the center of the slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacteria into the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Now, set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry. Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Pass the slide through the blue burner flame several times, with the bacteria side facing up. Then, once the slide has cooled, place a piece of precut lens paper over the heat-fixed smear. Next, turn on a hotplate to the highest setting, and bring a beaker of water to a boil.

Saturate the lens paper with the malachite green solution and, using tongs, place the slide on top of the beaker of boiling water to steam for 5 minutes. Keep the lens paper moist by adding more dye, one drop at a time, as needed. Next, again using tongs, pick up the slide from the beaker and remove and discard the lens paper. Allow the slide to cool for 2 minutes. Working over the sink, hold the slide at an angle, and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide. Now, hold the slide level and apply Safranin to completely cover the slide. Then, allow it to stand for 1 minute. Next, hold the slide at an angle and rinse as previously shown. Allow the slide to air dry on the benchtop. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide with a light microscope, with a 100X oil objective.

In the Gram staining protocol, two different colored stains can result. Dark purple staining indicates that the bacteria are Gram-positive and that they have retained the crystal violet stain. In contrast, reddish-pink staining is a characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria, which instead will be colored by the Safranin counterstain. Additionally, different shapes and arrangements of bacteria can be visualized after Gram staining. For example, it is possible to differentiate Cocci, or round bacteria, from rod-shaped Bacillus, or identify bacteria, which forms strands, compared to those which typically aggregate as clumps or occur singly.

In a capsule stained microscope image, the bacterial cells will typically be stained purple, and the background of the slide should be darkly stained. Against this dark background, the capsules of the bacteria, if present, will appear as a clear halo around the cells.

Lastly, in endospore staining, Vegetative cells will be stained red by the Safranin counterstain. If endospores are present in the sample, these will retain the malachite green stain and appear bluish-green in color.