顕微鏡検査と染色:グラム、カプセル、内胞染色

English

Share

Overview

ソース: リアノン M. ルベケ1, ナタリア マーティン1, アンドリュー J. ヴァン アルスト1, ビクター J. ディリタ1

1ミシガン州立大学微生物・分子遺伝学科、イーストランシング、ミシガン州、アメリカ合衆国

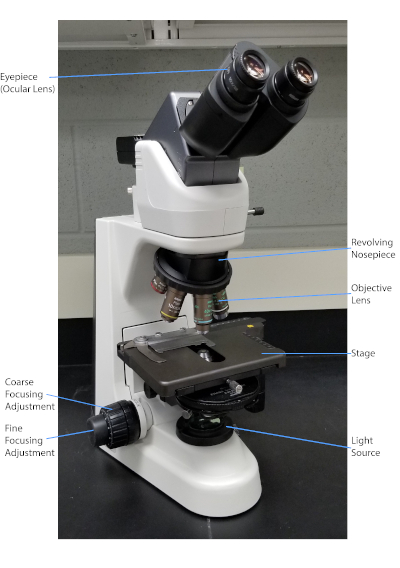

細菌は地球上のほぼどこにでも見られる多様な微生物です。多くの特性は、グラム染色の種類、形状と配置、カプセルの生産、胞子の形成を含むが、これらに限定されない、互いにそれらを区別するのに役立ちます。これらの特性を観察するために、1つは光顕微鏡を使用することができます。しかし、いくつかの細菌特性(例えば、サイズ、着色の欠如、屈折特性)は、光顕微鏡(1、2)だけで細菌を区別することが困難になります。細菌の種類を軽い顕微鏡で区別する場合は、染色細菌が必要です。2つの主要なタイプの軽微小顕微鏡は、シンプルで化合物です。それらの主な違いは、オブジェクトを拡大するために使用されるレンズの数です。単純な顕微鏡(例えば虫眼鏡)は、物体を拡大するためのレンズが1つしかありませんが、複合顕微鏡には倍率を高めるためのレンズが複数あります(図1)。複合顕微鏡は、物体の画像を作成するために光を収集するオブジェクトの近くに対物レンズを持っています。これは、画像を拡大するアイピース(眼レンズ)によって拡大されます。対物レンズとアイピースを組み合わせることで、単一レンズ単一レンズを使用するよりも高い倍率を実現します。通常、複合顕微鏡は、異なる倍率(1、2)を可能にするために、様々な力の複数の対物レンズを持っています。ここでは、グラム染色、カプセル染色、内胞汚れを用いて細菌を可視化する方法について説明します。

図1:典型的な化合物顕微鏡。顕微鏡の最も重要な部分は標識される。

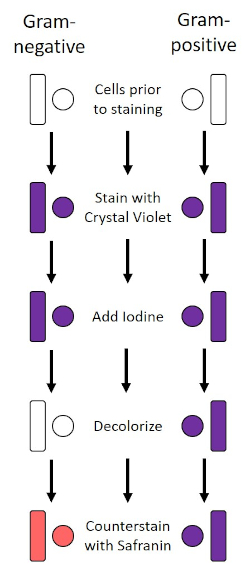

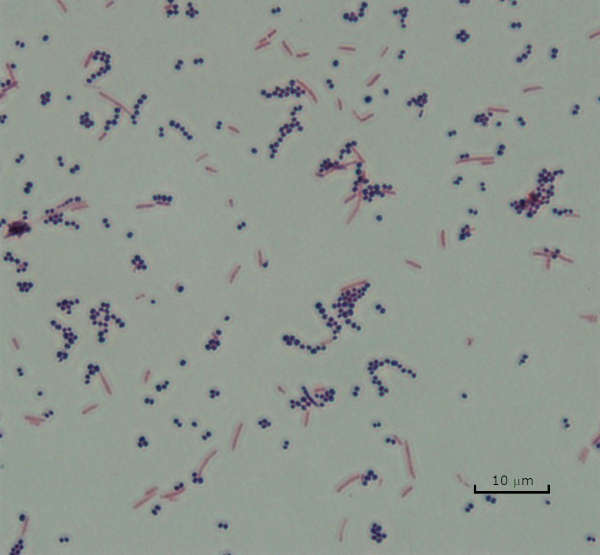

デンマークの細菌学者ハンス・クリスチャン・グラム(1)によって1884年に開発されたグラム染色は、細胞壁(1、2、3、4)の組成に基づいて細菌を分化する。簡単に言えば、細菌のスミアを顕微鏡スライド上に置き、細胞をスライドに付着させ、より容易に汚れを受け入れられるように熱固定する(1)。熱固定サンプルはクリスタルバイオレットで染色され、細胞を紫色に変えます。スライドは、細胞壁にクリスタルバイオレットを固定するヨウ素溶液で洗い流され、その後、非固定クリスタルバイオレットを洗い流すためにデカラーライザー(アルコール)が続きます。最後のステップでは、カウンターステイン、サフラニン、赤色色セルに添加されます(図2)。グラム陽性細菌は、デカラーライザーによって容易に浸透しない厚いペプチドギリカン層に起因する紫色に染色します。グラム陰性菌は、その薄いペプチドギリカン層と高い脂質含有量を有し、脱色剤で脱染し、サフラニンを添加すると赤色に染色される(図3)。グラム染色は、細胞を2種類(グラム陽性とグラム陰性)に分化するために使用され、細胞形状(球体または球体、ロッド、曲面ロッド、スパイラル)と配置(単一細胞、ペア、チェーン、グループ、クラスター)を区別するのにも役立ちます(1,3).

図2:グラム染色プロトコルの概略図。左の列は、プロトコルの各ステップでグラム陰性細菌がどのように反応するかを示しています。右の列は、グラム陽性の細菌がどのように反応するかを示しています。また、図示されているのは、バチル(または棒)と球体(または球)の2つの典型的な細菌細胞形状である。

図3:グラム染色結果。黄色ブドウ球菌(グラム陽性紫色のコッカス)と大腸菌(グラム陰性赤い棒)の混合物のグラム染色。

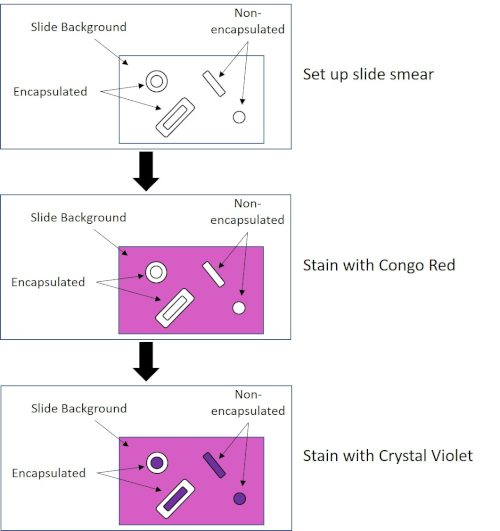

いくつかの細菌は、カプセル(3、5)と呼ばれる細胞外粘性外層を産生する。カプセルは、表面や他の細菌への付着、乾燥からの保護、および咽頭症からの保護を含むが、これらに限定されない様々な機能を有する保護構造である。カプセルは、通常、95%以上の水を含む多糖類で構成されていますが、一部はポリアルコールとポリアミン(5)を含むことがあります。そのほとんど非イオン性組成物と汚れを撃退する傾向があるため、単純な染色方法はカプセルでは動作しません。その代わりに、カプセル染色は、細胞および背景を染色する負の染色技術を使用し、カプセルを細胞の周りに明確なハローとして残す(図4)。カプセル染色は、細菌サンプルを顕微鏡スライド上の酸性染色に塗りつぶすることを含む。グラム染色とは異なり、細菌の汚れはカプセル染色中に熱固定されません。熱固定は、カプセルを破壊または脱水することができ、偽陰性(5)につながる。さらに、熱固定は細胞を収縮させることができ、その結果、カプセルと間違えられ得る細胞の周りのクリアリングを行うことができ、偽陽性(3)を引き起こす。酸性染色は、スライドの背景を着色します。基本的な染色をフォローアップしながら、クリスタルバイオレットは、細菌細胞自体を着色し、カプセルを染色されず、細胞とスライドの背景との間に明確なハローとして現れる(図5)。従来、インドのインクは、これらの粒子がカプセルに浸透できないため、酸性染色剤として使用されてきました。したがって、カプセルも細胞もインドのインクによって染色されていない。代わりに、背景が汚されます。コンゴレッド、ニロシン、またはエオシンは、インドのインクの代わりに使用することができます。カプセル染色は、患者サンプルから培養物を見て、適切な患者治療を導くときに医師が細菌感染症を診断するのに役立ちます。封入細菌によって引き起こされる一般的な疾患には、肺炎、髄膜炎、およびサルモネラ症が含まれる。

図4:カプセル染色プロトコルの概略図。上部パネルは、汚れ塗布前のスライドスミアを示しています。中央のパネルは、スライドと細菌が一次染色、コンゴレッドの後にどのように見えるかを示しています。最後のパネルは、スライドと細菌がカウンターステイン、クリスタルバイオレットの後にどのように見えるかを示しています。

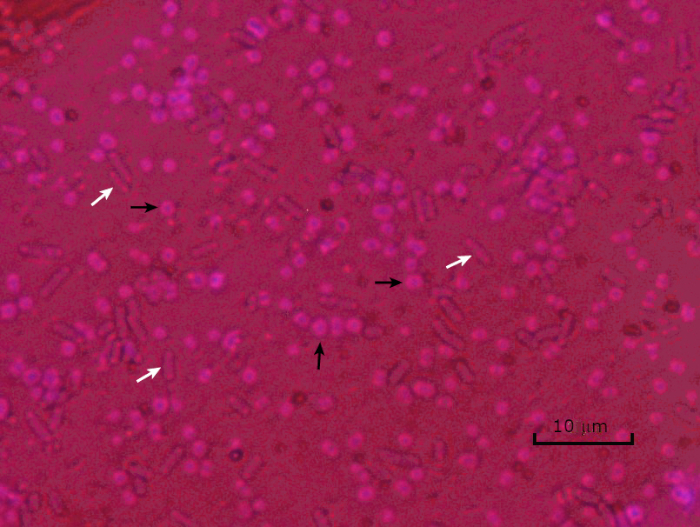

図5:カプセル染色結果。封入されたアシネトバクター・バウマンニ(黒い矢印で示される)および非封入大腸菌(白い矢印で示される)のカプセル染色。背景が暗く、A.バウマンニ細胞が紫色に染色されていることに注意してください。A.バウマンニ細胞の周りのカプセルはハローとして明らかであるが、大腸菌はハローを持たない。

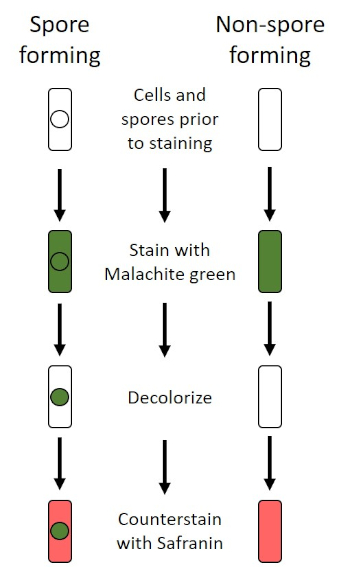

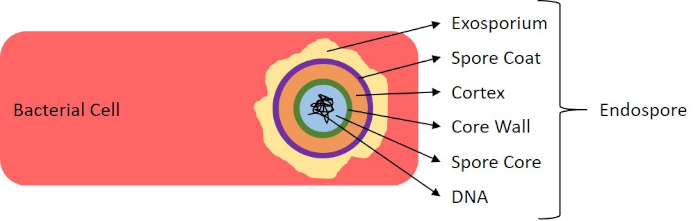

有害な条件(例えば、栄養制限、極端な温度、脱水)では、一部の細菌は内在性胞子を産生し、物理的および化学的損傷に対して耐性のある代謝的に不活性な構造(1、2、8、9)を産生する。内胞子は、細菌が細胞の遺伝物質を保護することによって過酷な条件を生き残ることを可能にします。いったん条件が成長に有利な状態になったら、胞子は発芽し、細菌の増殖が続く。エンドスポールは、通常染色に使用される染料に対して不透過性であるため、標準的な染色技術では染色が困難です(1,9)。内胞子を染色するために日常的に使用される技術は、一次染色マラカイトグリーン、細胞材料に比較的弱く結合する水溶性染色、および熱を使用して、汚れを壊すことを可能にするシェーファーフルトン法(図6)です。胞子の皮質を通して(図7)。これらのステップは、成長する細胞(内胞子生物学の文脈で栄養細胞と呼ばれる)、ならびに内胞子および任意の自由胞子(もはや前の細胞の封筒内になくなっているもの)を着色する。栄養細胞は、マラカイトグリーンを除去するために水で洗浄されます。内胞子は胞子内のマラカイトグリーンを加熱することに起因する汚れを保持します。最後に、栄養細胞をサフラニンで逆染色して可視化する(図8)。エンド胞子の染色は、細菌を胞子原型および非胞子フォーマーに分化させるだけでなく、胞子がサンプル中に存在するかどうかを決定するのに役立ち、もし存在する場合、発芽時に細菌汚染を引き起こす可能性がある。

図6:内胞染色プロトコルの概略図。左の列は、胞形細菌がプロトコルの各ステップでどのように反応するかを示しています。右の列は、非胞毛形成細菌がどのように反応するかを示しています。

図7:内胞構造図種々の胞直構造を標識した内胞を含む細菌細胞。

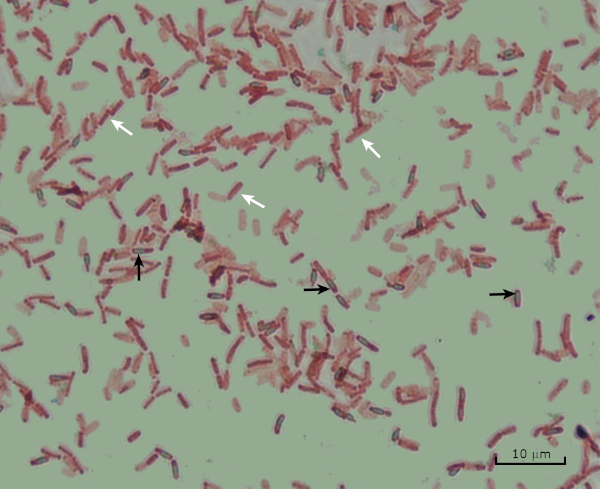

図8:内胞染色結果。バチルス・サビリスのエンドスポ胞の典型的な染色.栄養細胞(白い矢印で示される)は赤く染色され、内胞子(黒い矢印で示される)は緑色に染色されます。

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Bacteria have distinguishing characteristics that can aid in their identification. Some of these characteristics can be observed by staining and light microscopy. Three staining techniques useful for observing these characteristics are Gram staining, Capsule staining, and Endospore staining. Each technique identifies different characteristics of bacteria and can be used to help physicians recommend treatments for patients, identify potential contaminants in samples or food products, and verify sample sterility.

References

- Black, J. G. Microbiology Principles and Explorations, 4th edition. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (1999)

- Madigan, M. T. and J. M. Martinko. Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 11th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (2006).

- Leboffe, M. J., and B. E. Pierce. A Photographic Atlas for the Microbiology Laboratory, 2nd ed. Morton Publishing Company, Englewood, Colorado. (1996).

- Smith, A. C. and M. A. Hussey. Gram stain protocols. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.2886. (2005).

- Hughes, R. B. and A. C. Smith. Capsule Stain Protocols Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3041. (2007).

- Anthony, E. E. Jr. A note on capsule staining. Science 73(1890):319-320 (1931).

- Finegold, S. M., W. J. Martin, and E. G. Scott. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology, 5th edition. The C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Missouri. (1978).

- Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. (1994).

- Hussey, M. A. and A. Zayaitz. Endospore Stain Protocol. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3112. (2007).

Transcript

Bacteria are microscopic living organisms that have many distinguishing characteristics such as shape, arrangement of cells, whether or not they produce capsules, and if they form spores. These features can all be visualized by staining and aid in the identification and classification of different bacterial species.

To examine the first two characteristics of cell shape and arrangement, we can use a simple technique called Gram staining. Here, crystal violet is applied to bacteria, which have been heat-fixed onto a slide. Next, Gram’s iodine solution is added to the slide, resulting in the formation of an insoluble complex between the crystal violet and the Gram’s iodine solution. A decolorizer is then applied and any bacteria with a thick peptidoglycan layer will stain purple, as this layer is not easily penetrated by the decolorizer. These bacteria are referred to as Gram-positive.

Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer and will de-stain the decolorizer, losing the purple color. However, they will stain reddish-pink when a safranin counterstain is added, which binds to a lipopolysaccharide layer on their outside. Once stained, the cells can be observed for morphology, size, and arrangement, such as in chains or clusters, which further aids in classification and identification.

Another useful technique in the microbiologist’s toolkit is the capsule stain, used to visualize external capsules that surround some types of bacterial cells. Due to the capsule’s non-ionic composition and tendency to repel stains, simple staining methods won’t work. Instead, a negative staining technique is used, which first stains the background with an acidic colorant, such as Congo red, before the bacterial cells are stained with crystal violet. This leaves any capsule present as a clear halo around the cells.

The final major staining technique covered here can help determine if the bacteria being studied forms spores. In adverse conditions, some bacteria produce endospores, dormant, tough, non-reproductive structures whose primary function is to ensure the survival of bacteria through periods of environmental stress, like extreme temperatures or dehydration. However, not all bacterial species make endospores, and they are difficult to stain with standard techniques because they are impermeable to many dyes. The Schaeffer-Fulton method uses malachite green stain, which is applied to the bacteria fixed to a slide. The slide is then washed with water before being counterstained with Safranin. Vegetative cells will appear pinkish-red, while any endospores present will appear green. In this video, you will learn how to perform these common bacterial staining techniques and then examine the staining samples using light microscopy.

To begin the procedure, tie back long hair and put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves.

Then, clean a fresh microscope slide with a laboratory wipe. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X phosphate-buffered saline onto the first slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacterial colony in the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry.

Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Using tongs, pass the slide through the burner flame several times, with the bacteria side up, taking care not to hold the slide in the flame too long, which may distort the cells.

Now, working over the sink, hold the slide level and apply several drops of Gram’s crystal violet to completely cover the bacterial smear and then place the slide onto the bench to stand for 45 seconds. Next, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacterial smear directly. Now, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s iodine solution to completely cover the stained bacteria and then allow it to stand for another 45 seconds. Next, carefully rinse the iodine from the slide, as shown previously. While holding the slide at an angle, add a few drops of Gram’s decolorizer to the slide, allowing it to run down over the stained bacteria, just until the run-off is clear, for approximately 5 seconds. Immediately, rinse with water as shown previously. This will limit over-decolorizing the smear. Next, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s safranin counterstain to completely cover the stained bacteria. After 45 seconds, gently rinse the Safranin from the slide with water, as shown previously, and then blot dry with paper towels.

Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective lens.

To begin this staining protocol, first put on the correct personal protective equipment and then ensure that the glass slides that will be used are clean.

Next, prepare the solutions. To make 1% crystal violet solution, mix 0.25 grams of crystal violet powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Then, prepare 1% Congo red solution by mixing 0.25 grams of Congo red powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Now, pipette 10 microliters of the Congo red solution onto the slide. Using a clean, sterile pipette tip, select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Then, smear the bacterial colony into the dye to produce a thin, even layer. Completely air dry the bacterial slide for 5-7 minutes. Once the slide is dry, flood the smear with enough 1% crystal violet to cover the smear and let it sit for 1 minute. Now, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacteria directly. Continue holding the slide at a 45-degree angle until completely air-dried. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective.

To perform endospore staining, first, prepare a 0.5% malachite green solution by mixing 0. 125 grams of malachite green powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water, and then vortex the solution until dissolved. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X PBS onto the center of the slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacteria into the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Now, set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry. Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Pass the slide through the blue burner flame several times, with the bacteria side facing up. Then, once the slide has cooled, place a piece of precut lens paper over the heat-fixed smear. Next, turn on a hotplate to the highest setting, and bring a beaker of water to a boil.

Saturate the lens paper with the malachite green solution and, using tongs, place the slide on top of the beaker of boiling water to steam for 5 minutes. Keep the lens paper moist by adding more dye, one drop at a time, as needed. Next, again using tongs, pick up the slide from the beaker and remove and discard the lens paper. Allow the slide to cool for 2 minutes. Working over the sink, hold the slide at an angle, and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide. Now, hold the slide level and apply Safranin to completely cover the slide. Then, allow it to stand for 1 minute. Next, hold the slide at an angle and rinse as previously shown. Allow the slide to air dry on the benchtop. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide with a light microscope, with a 100X oil objective.

In the Gram staining protocol, two different colored stains can result. Dark purple staining indicates that the bacteria are Gram-positive and that they have retained the crystal violet stain. In contrast, reddish-pink staining is a characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria, which instead will be colored by the Safranin counterstain. Additionally, different shapes and arrangements of bacteria can be visualized after Gram staining. For example, it is possible to differentiate Cocci, or round bacteria, from rod-shaped Bacillus, or identify bacteria, which forms strands, compared to those which typically aggregate as clumps or occur singly.

In a capsule stained microscope image, the bacterial cells will typically be stained purple, and the background of the slide should be darkly stained. Against this dark background, the capsules of the bacteria, if present, will appear as a clear halo around the cells.

Lastly, in endospore staining, Vegetative cells will be stained red by the Safranin counterstain. If endospores are present in the sample, these will retain the malachite green stain and appear bluish-green in color.