Mikroskopie und Färbungen: Gram-, Kapsel- und Endosporenfärbung

English

Share

Overview

Quelle: Rhiannon M. LeVeque1, Natalia Martin1, Andrew J. Van Alst1, und Victor J. DiRita1

1 Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, Vereinigte Staaten von Amerika

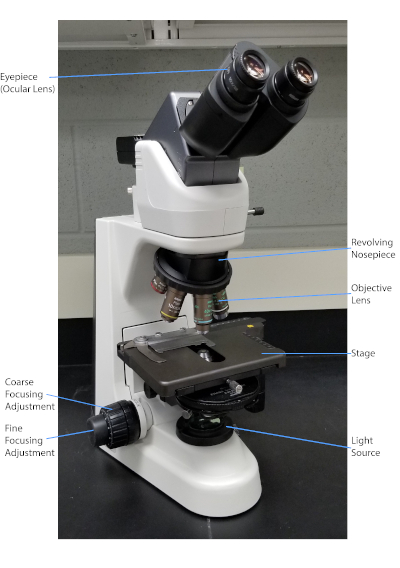

Bakterien sind verschiedene Mikroorganismen, die fast überall auf der Erde vorkommen. Viele Eigenschaften helfen, sie voneinander zu unterscheiden, einschließlich, aber nicht beschränkt auf Gram-Färbung Art, Form und Anordnung, Produktion von Kapsel, und Bildung von Sporen. Um diese Eigenschaften zu beobachten, kann man Lichtmikroskopie verwenden; Einige bakterielle Eigenschaften (z. B. Größe, fehlende Färbung und Brechungseigenschaften) machen es jedoch schwierig, Bakterien nur mit einem Lichtmikroskop zu unterscheiden (1, 2). Färben von Bakterien ist notwendig, wenn Bakterientypen mit Lichtmikroskopie unterschieden werden. Die beiden Haupttypen von Lichtmikroskopen sind einfach und zusammengesetzt. Der Hauptunterschied zwischen ihnen ist die Anzahl der Linsen, die verwendet werden, um das Objekt zu vergrößern. Einfache Mikroskope (z. B. eine Lupe) haben nur eine Linse, um ein Objekt zu vergrößern, während zusammengesetzte Mikroskope mehrere Linsen haben, um die Vergrößerung zu verbessern (Abbildung 1). Zusammengesetzte Mikroskope haben eine Objektivlinse in der Nähe des Objekts, die Licht sammelt, um ein Bild des Objekts zu erstellen. Dies wird dann durch das Okular (Augenlinse) vergrößert, das das Bild vergrößert. Die Kombination von Objektiv und Okular ermöglicht eine höhere Vergrößerung als die Verwendung einer einzigen Linse allein. In der Regel verfügen Verbundmikroskope über mehrere Objektivlinsen mit unterschiedlichen Leistungen, um eine unterschiedliche Vergrößerung zu ermöglichen (1, 2). Hier werden wir die Visualisierung von Bakterien mit Gramflecken, Kapselflecken und Endosporenflecken diskutieren.

Abbildung 1: Ein typisches Zusammengesetzten Mikroskop. Die wichtigsten Teile des Mikroskops sind beschriftet.

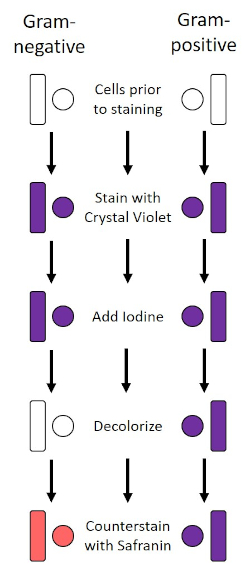

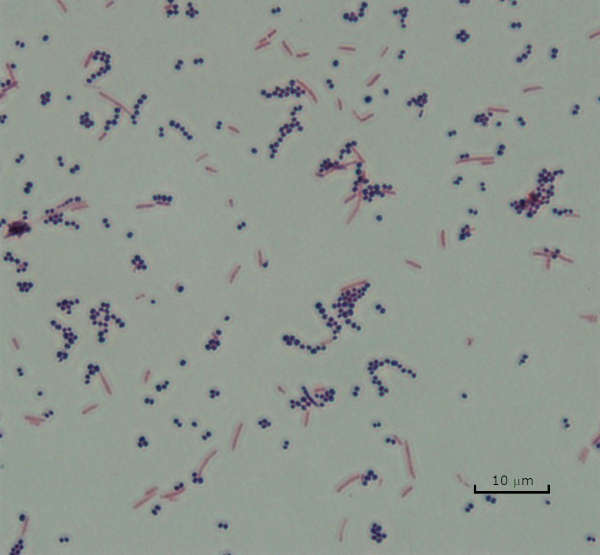

Der Gram-Fleck, der 1884 vom dänischen Bakteriologen Hans Christian Gram (1) entwickelt wurde, unterscheidet Bakterien anhand der Zusammensetzung der Zellwand (1, 2, 3, 4). Kurz gesagt, wird ein bakterielles Abstrich auf einem Mikroskopschlitten platziert und dann wärmefixiert, um die Zellen am Dia zu haften und sie leichter zu akzeptieren, Flecken zu akzeptieren (1). Die wärmefeste Probe ist mit Crystal Violet gefärbt und verwandelt die Zellen violett. Die Rutsche wird mit einer Jodlösung gespült, die das Kristallviolett an der Zellwand fixiert, gefolgt von einem Decolorizer (ein Alkohol), um jedes nicht fixierte Kristallviolett wegzuwaschen. Im letzten Schritt wird ein Gegenfleck, Safranin, zu den Farbzellen rot hinzugefügt (Abbildung 2). Gram-positive Bakterien färben lila aufgrund der dicken Peptidoglykan-Schicht, die nicht leicht durch den Decolorizer durchdrungen wird; Gram-negative Bakterien, mit ihrer dünneren Peptidhundlykanschicht und höherem Lipidgehalt, destain mit dem Decolorizer und sind rot gefleckt, wenn Safranin hinzugefügt wird (Abbildung 3). Die Gramfärbung wird verwendet, um Zellen in zwei Typen (Gram-positiv und Gram-negativ) zu unterscheiden und ist auch nützlich, um Zellform (Kugeln oder Koks, Stäbe, gekrümmte Stäbe und Spiralen) und Anordnung (einzelne Zellen, Paare, Ketten, Gruppen und Cluster) zu unterscheiden (1, 3) .

Abbildung 2: Schematic des Gram Staining Protocol. Die linke Spalte zeigt, wie gramnegative Bakterien bei jedem Schritt des Protokolls reagieren. Die rechte Spalte zeigt, wie grampositive Bakterien reagieren. Gezeigt werden auch zwei typische bakterielle Zellformen: die Bazillen (oder Stäbe) und die Kokzien (oder Kugeln).

Abbildung 3: Gram Staining Ergebnisse. Ein Gram-Fleck einer Mischung aus Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive lila Kokzi) und Escherichia coli (Gram-negative rote Stäbe).

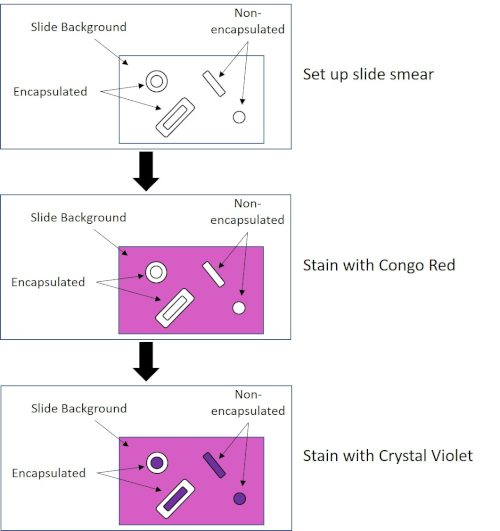

Einige Bakterien produzieren eine extrazelluläre viskose äußere Schicht, die als Kapsel bezeichnet wird (3, 5). Kapseln sind Schutzstrukturen mit verschiedenen Funktionen, einschließlich, aber nicht beschränkt auf die Haftung an Oberflächen und anderen Bakterien, Schutz vor Austrocknung und Schutz vor Phagozytose. Kapseln bestehen in der Regel aus Polysacchariden, die mehr als 95% Wasser enthalten, aber einige können Polyalkohole und Polyame enthalten (5). Aufgrund ihrer meist nicht-ionischen Zusammensetzung und der Tendenz, Flecken abzustoßen, funktionieren einfache Färbemethoden nicht mit Kapsel; Stattdessen verwendet die Kapselfärbung eine negative Färbetechnik, die die Zellen und den Hintergrund färbt und die Kapsel als klaren Halo um die Zellen lässt (1, 3) (Abbildung 4). Kapselfärbung beinhaltet verschmieren eine bakterielle Probe in einen sauren Fleck auf einem Mikroskop-Dia. Im Gegensatz zur Gram-Färbung wird der bakterielle Abstrich während eines Kapselflecks nicht wärmefixiert. Wärmefixierung kann die Kapsel stören oder dehydrieren, was zu falschen Negativen führt (5). Darüber hinaus kann die Wärmefixierung Zellen schrumpfen, was zu einer Lichtung um die Zelle führt, die als Kapsel verwechselt werden kann, was zu falschen Positivmeldungen führt (3). Der saure Fleck färbt den Diahintergrund; Während nacheinem Grundfleck, Crystal Violet, die Bakterienzellen selbst färbt, so dass die Kapsel unbefleckt bleibt und als klarer Halo zwischen den Zellen und dem Diahintergrund erscheint (Abbildung 5). Traditionell wurde Indientinte als saurer Fleck verwendet, da diese Partikel nicht in die Kapsel eindringen können. Daher ist weder die Kapsel noch die Zelle durch Indische Tinte gefärbt; stattdessen ist der Hintergrund befleckt. Kongo Rot, Nigrosin oder Eosin kann anstelle von Indien Tinte verwendet werden. Kapselfärbung kann Ärzten helfen, bakterielle Infektionen zu diagnostizieren, wenn sie Kulturen aus Patientenproben betrachten und geeignete Patientenbehandlungen leiten. Häufige Krankheiten, die durch verkapselte Bakterien verursacht werden, sind Lungenentzündung, Meningitis und Salmonellose.

Abbildung 4: Schematic des Capsule Staining Protocol. Das obere Panel zeigt den Diaabstrich vor jeder Fleckenanwendung an. Die mittlere Tafel zeigt, wie die Rutsche und Bakterien nach dem primären Fleck, Congo Red, aussehen. Das letzte Panel zeigt, wie die Rutsche und Bakterien nach dem Gegenfleck Crystal Violet aussehen.

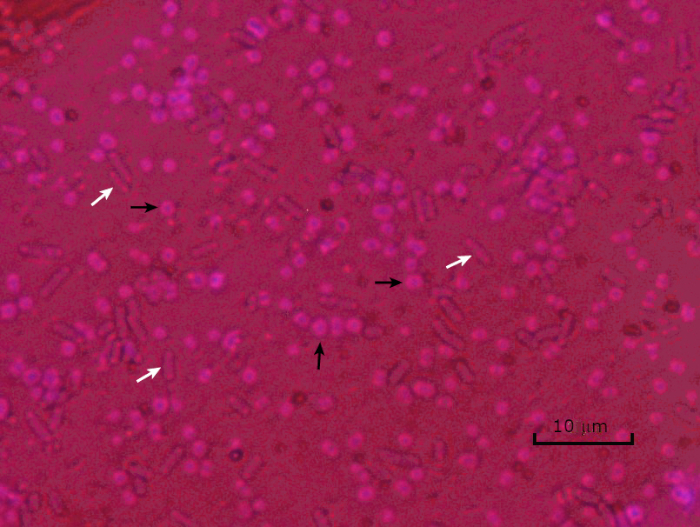

Abbildung 5: Capsule Staining Ergebnisse. Kapselfärbung von verkapselten Acinetobacter baumannii (mit schwarzen Pfeilen bezeichnet) und nicht verkapselter Escherichia coli (mit weißen Pfeilen bezeichnet). Beachten Sie, dass der Hintergrund dunkel ist und A. baumannii Zellen violett gefärbt sind. Die Kapsel um A. baumannii Zellen ist als Halo offensichtlich, während E. coli keinen Halo hat.

Unter widrigen Bedingungen (z. B. Nährstoffbegrenzung, extreme Temperaturen oder Dehydrierung) produzieren einige Bakterien Endosporen, metabolisch inaktive Strukturen, die gegen physikalische und chemische Schäden resistent sind (1, 2, 8, 9). Endosporen ermöglichen es dem Bakterium, harte Bedingungen zu überleben, indem es das genetische Material der Zellen schützt; sobald die Bedingungen für das Wachstum günstig sind, keimen Sporen, und das Bakterienwachstum setzt sich fort. Endosporen sind mit Standard-Färbetechniken schwer zu färben, da sie undurchlässig für Farbstoffe sind, die typischerweise für die Färbung verwendet werden (1, 9). Die Technik, die routinemäßig verwendet wird, um Endosporen zu färben, ist die Schaeffer-Fulton-Methode (Abbildung 6),die den primären Fleck Malachite Green verwendet, einen wasserlöslichen Fleck, der relativ schwach an zelluläres Material bindet, und Wärme, damit der Fleck brechen kann. durch den Kortex der Sporen (Abbildung 7). Diese Schritte färben die wachsenden Zellen (im Kontext der Endosporenbiologie als vegetative Zellen bezeichnet) sowie Endosporen und freie Sporen (die nicht mehr innerhalb der früheren Zellhülle). Vegetative Zellen werden mit Wasser gewaschen, um Malachitgrün zu entfernen; Endosporen behalten den Fleck durch Erhitzen der Malachitgrün innerhalb der Sporen. Schließlich werden die vegetativen Zellen mit Safranin konterkariert, um sie zu visualisieren (Abbildung 8). Die Färbung von Endosporen hilft, Bakterien in Sporenformer und Nicht-Sporen-Former zu differenzieren, und bestimmt, ob Sporen in einer Probe vorhanden sind, die, wenn vorhanden, bei der Keimung zu einer bakteriellen Kontamination führen könnte.

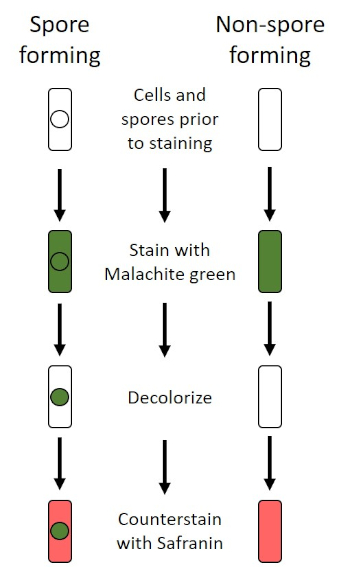

Abbildung 6: Schematic des Endospore Staining Protocol. Die linke Spalte zeigt, wie sporenbildende Bakterien bei jedem Schritt des Protokolls reagieren. Die rechte Spalte zeigt, wie nicht sporenbildende Bakterien reagieren.

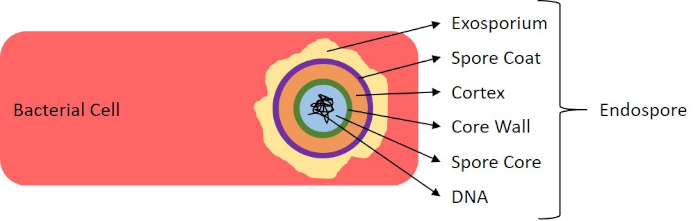

Abbildung 7: Diagramm der Endosporenstruktur. Bakterielle Zelle, die eine Endospore mit den verschiedenen Sporenstrukturen enthält.

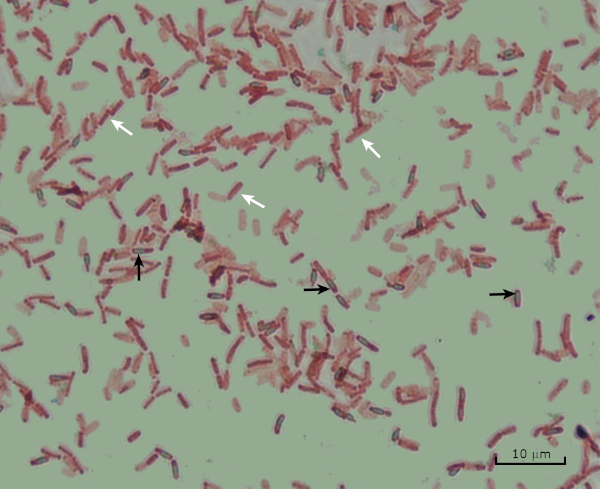

Abbildung 8: Endospore Färbung Ergebnisse. Eine typische Färbung von Endosporen von Bacillus subtilis. Die vegetativen Zellen (mit den weißen Pfeilen bezeichnet) sind rot gefärbt, während die Endosporen (mit den schwarzen Pfeilen bezeichnet) grün gebeizt sind.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Bacteria have distinguishing characteristics that can aid in their identification. Some of these characteristics can be observed by staining and light microscopy. Three staining techniques useful for observing these characteristics are Gram staining, Capsule staining, and Endospore staining. Each technique identifies different characteristics of bacteria and can be used to help physicians recommend treatments for patients, identify potential contaminants in samples or food products, and verify sample sterility.

References

- Black, J. G. Microbiology Principles and Explorations, 4th edition. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (1999)

- Madigan, M. T. and J. M. Martinko. Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 11th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (2006).

- Leboffe, M. J., and B. E. Pierce. A Photographic Atlas for the Microbiology Laboratory, 2nd ed. Morton Publishing Company, Englewood, Colorado. (1996).

- Smith, A. C. and M. A. Hussey. Gram stain protocols. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.2886. (2005).

- Hughes, R. B. and A. C. Smith. Capsule Stain Protocols Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3041. (2007).

- Anthony, E. E. Jr. A note on capsule staining. Science 73(1890):319-320 (1931).

- Finegold, S. M., W. J. Martin, and E. G. Scott. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology, 5th edition. The C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Missouri. (1978).

- Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. (1994).

- Hussey, M. A. and A. Zayaitz. Endospore Stain Protocol. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3112. (2007).

Transcript

Bacteria are microscopic living organisms that have many distinguishing characteristics such as shape, arrangement of cells, whether or not they produce capsules, and if they form spores. These features can all be visualized by staining and aid in the identification and classification of different bacterial species.

To examine the first two characteristics of cell shape and arrangement, we can use a simple technique called Gram staining. Here, crystal violet is applied to bacteria, which have been heat-fixed onto a slide. Next, Gram’s iodine solution is added to the slide, resulting in the formation of an insoluble complex between the crystal violet and the Gram’s iodine solution. A decolorizer is then applied and any bacteria with a thick peptidoglycan layer will stain purple, as this layer is not easily penetrated by the decolorizer. These bacteria are referred to as Gram-positive.

Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer and will de-stain the decolorizer, losing the purple color. However, they will stain reddish-pink when a safranin counterstain is added, which binds to a lipopolysaccharide layer on their outside. Once stained, the cells can be observed for morphology, size, and arrangement, such as in chains or clusters, which further aids in classification and identification.

Another useful technique in the microbiologist’s toolkit is the capsule stain, used to visualize external capsules that surround some types of bacterial cells. Due to the capsule’s non-ionic composition and tendency to repel stains, simple staining methods won’t work. Instead, a negative staining technique is used, which first stains the background with an acidic colorant, such as Congo red, before the bacterial cells are stained with crystal violet. This leaves any capsule present as a clear halo around the cells.

The final major staining technique covered here can help determine if the bacteria being studied forms spores. In adverse conditions, some bacteria produce endospores, dormant, tough, non-reproductive structures whose primary function is to ensure the survival of bacteria through periods of environmental stress, like extreme temperatures or dehydration. However, not all bacterial species make endospores, and they are difficult to stain with standard techniques because they are impermeable to many dyes. The Schaeffer-Fulton method uses malachite green stain, which is applied to the bacteria fixed to a slide. The slide is then washed with water before being counterstained with Safranin. Vegetative cells will appear pinkish-red, while any endospores present will appear green. In this video, you will learn how to perform these common bacterial staining techniques and then examine the staining samples using light microscopy.

To begin the procedure, tie back long hair and put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves.

Then, clean a fresh microscope slide with a laboratory wipe. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X phosphate-buffered saline onto the first slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacterial colony in the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry.

Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Using tongs, pass the slide through the burner flame several times, with the bacteria side up, taking care not to hold the slide in the flame too long, which may distort the cells.

Now, working over the sink, hold the slide level and apply several drops of Gram’s crystal violet to completely cover the bacterial smear and then place the slide onto the bench to stand for 45 seconds. Next, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacterial smear directly. Now, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s iodine solution to completely cover the stained bacteria and then allow it to stand for another 45 seconds. Next, carefully rinse the iodine from the slide, as shown previously. While holding the slide at an angle, add a few drops of Gram’s decolorizer to the slide, allowing it to run down over the stained bacteria, just until the run-off is clear, for approximately 5 seconds. Immediately, rinse with water as shown previously. This will limit over-decolorizing the smear. Next, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s safranin counterstain to completely cover the stained bacteria. After 45 seconds, gently rinse the Safranin from the slide with water, as shown previously, and then blot dry with paper towels.

Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective lens.

To begin this staining protocol, first put on the correct personal protective equipment and then ensure that the glass slides that will be used are clean.

Next, prepare the solutions. To make 1% crystal violet solution, mix 0.25 grams of crystal violet powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Then, prepare 1% Congo red solution by mixing 0.25 grams of Congo red powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Now, pipette 10 microliters of the Congo red solution onto the slide. Using a clean, sterile pipette tip, select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Then, smear the bacterial colony into the dye to produce a thin, even layer. Completely air dry the bacterial slide for 5-7 minutes. Once the slide is dry, flood the smear with enough 1% crystal violet to cover the smear and let it sit for 1 minute. Now, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacteria directly. Continue holding the slide at a 45-degree angle until completely air-dried. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective.

To perform endospore staining, first, prepare a 0.5% malachite green solution by mixing 0. 125 grams of malachite green powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water, and then vortex the solution until dissolved. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X PBS onto the center of the slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacteria into the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Now, set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry. Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Pass the slide through the blue burner flame several times, with the bacteria side facing up. Then, once the slide has cooled, place a piece of precut lens paper over the heat-fixed smear. Next, turn on a hotplate to the highest setting, and bring a beaker of water to a boil.

Saturate the lens paper with the malachite green solution and, using tongs, place the slide on top of the beaker of boiling water to steam for 5 minutes. Keep the lens paper moist by adding more dye, one drop at a time, as needed. Next, again using tongs, pick up the slide from the beaker and remove and discard the lens paper. Allow the slide to cool for 2 minutes. Working over the sink, hold the slide at an angle, and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide. Now, hold the slide level and apply Safranin to completely cover the slide. Then, allow it to stand for 1 minute. Next, hold the slide at an angle and rinse as previously shown. Allow the slide to air dry on the benchtop. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide with a light microscope, with a 100X oil objective.

In the Gram staining protocol, two different colored stains can result. Dark purple staining indicates that the bacteria are Gram-positive and that they have retained the crystal violet stain. In contrast, reddish-pink staining is a characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria, which instead will be colored by the Safranin counterstain. Additionally, different shapes and arrangements of bacteria can be visualized after Gram staining. For example, it is possible to differentiate Cocci, or round bacteria, from rod-shaped Bacillus, or identify bacteria, which forms strands, compared to those which typically aggregate as clumps or occur singly.

In a capsule stained microscope image, the bacterial cells will typically be stained purple, and the background of the slide should be darkly stained. Against this dark background, the capsules of the bacteria, if present, will appear as a clear halo around the cells.

Lastly, in endospore staining, Vegetative cells will be stained red by the Safranin counterstain. If endospores are present in the sample, these will retain the malachite green stain and appear bluish-green in color.