Microscopía y tinción: Tinción de Gram, cápsula y endosporas

English

Share

Overview

Fuente: Rhiannon M. LeVeque1, Natalia Martin1, Andrew J. Van Alst1, y Victor J. DiRita1

1 Departamento de Microbiología y Genética Molecular, Universidad Estatal de Michigan, East Lansing, Michigan, Estados Unidos de América

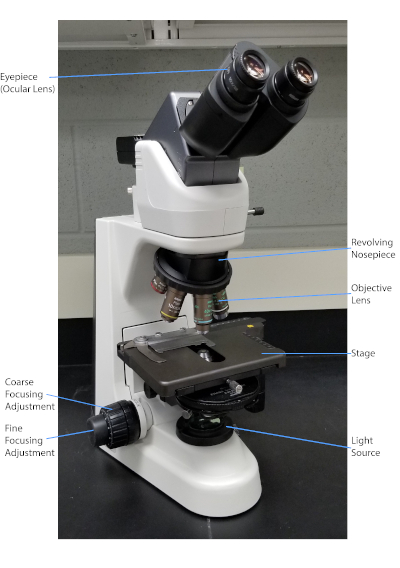

Las bacterias son microorganismos diversos que se encuentran en casi todas partes de la Tierra. Muchas propiedades ayudan a distinguirlos entre sí, incluyendo pero no limitado a tipo de tinción de Gram, forma y disposición, producción de cápsulas, y la formación de esporas. Para observar estas propiedades, se puede utilizar microscopía de luz; sin embargo, algunas características bacterianas (por ejemplo, el tamaño, la falta de coloración y las propiedades refractivas) hacen que sea difícil distinguir las bacterias únicamente con un microscopio ligero (1, 2). Las bacterias de la tinción son necesarias al distinguir los tipos bacterianos con microscopía de luz. Los dos tipos principales de microscopios de luz son simples y compuestos. La principal diferencia entre ellos es el número de lentes utilizadas para magnificar el objeto. Los microscopios simples (por ejemplo, una lupa) tienen una sola lente para magnificar un objeto, mientras que los microscopios compuestos tienen varias lentes para mejorar el aumento (Figura 1). Los microscopios compuestos tienen una lente objetiva cerca del objeto que recoge la luz para crear una imagen del objeto. Esto es emagnificado por el ocular (lente ocular) que agranda la imagen. La combinación de la lente objetivo y el ocular permite un aumento más alto que el uso de una sola lente. Por lo general, los microscopios compuestos tienen múltiples lentes objetivas de diferentes potencias para permitir un aumento diferente (1, 2). Aquí, vamos a discutir la visualización de bacterias con manchas de Gram, manchas de cápsula, y manchas de endospora.

Figura 1: Un microscopio compuesto típico. Las partes más importantes del microscopio están etiquetadas.

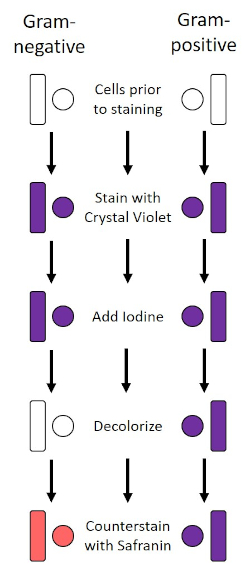

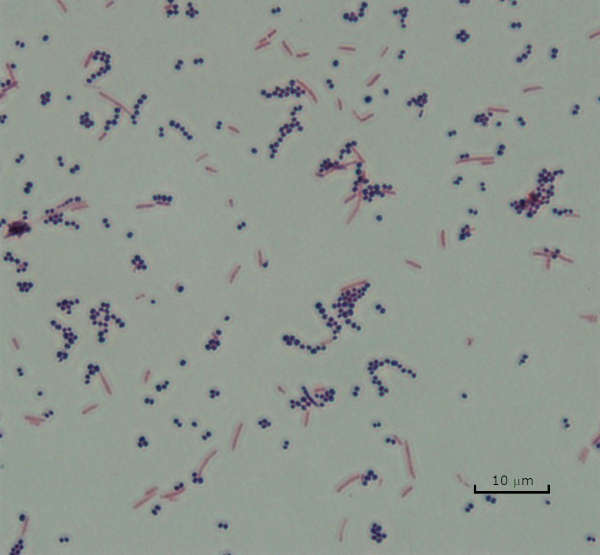

La tinción Gram, desarrollada en 1884 por el bacteriólogo danés Hans Christian Gram (1), diferencia las bacterias en función de la composición de la pared celular (1, 2, 3, 4). Brevemente, se coloca un frotis bacteriano en un portaobjetos del microscopio y luego se fija térmicamente para adherir las células a la diapositiva y hacerlas aceptar más fácilmente de las manchas (1). La muestra termofija se tiñe con Cristal Violeta, convirtiendo las células en púrpura. La diapositiva se lava con una solución de yodo, que fija el Cristal Violet a la pared celular, seguido de un decolorante (un alcohol) para lavar cualquier Crystal Violet no fijo. En el paso final, se añade una contramancha, Safranin, a las celdas de color rojo (Figura 2). Bacterias Gram-positivas mancha púrpura debido a la gruesa capa de peptidoglycan que no es fácilmente penetrado por el decolorante; Bacterias gramnegativas, con su capa de peptidoglycan más delgada y mayor contenido de lípidos, descolorante con el decolorante y se contratienen en rojo cuando se añade Safranin (Figura 3). La tinción de Gram se utiliza para diferenciar las células en dos tipos (Gram-positivo y Gram-negativo) y también es útil para distinguir la forma de la célula (esferas o cocci, varillas, varillas curvas y espirales) y la disposición (células individuales, pares, cadenas, grupos y racimos) (1, 3) .

Figura 2: Esquema del protocolo Gram Staining Protocol. La columna izquierda muestra cómo reaccionan las bacterias Gram-negativas en cada paso del protocolo. La columna derecha muestra cómo reaccionan las bacterias Gram-positivas. Además, se muestran dos formas celulares bacterianas típicas: los bacilos (o varillas) y los cocci (o esferas).

Figura 3: Resultados de la tinción de Gram. Una tinción de Gram de una mezcla de Staphylococcus aureus (cocci púrpura Gram-positivo) y Escherichia coli (barras rojas gramnegativas).

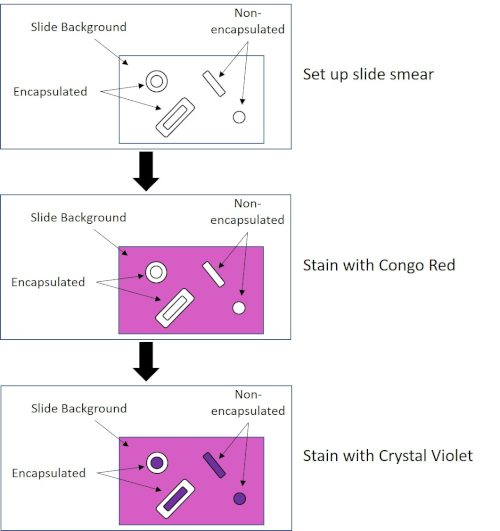

Algunas bacterias producen una capa externa viscosa extracelular llamada cápsula (3, 5). Las cápsulas son estructuras protectoras con varias funciones, incluyendo pero no limitado a la adherencia a las superficies y otras bacterias, protección contra la desecación, y protección contra la fagocitosis. Cápsulas se componen típicamente de polisacáridos que contienen más del 95% de agua, pero algunos pueden contener polialcohols y poliaminas (5). Debido a su composición principalmente no iónica y su tendencia a repeler las manchas, los métodos de tinción simples no funcionan con la cápsula; en su lugar, la tinción de cápsulas utiliza una técnica de tinción negativa que mancha las células y el fondo, dejando la cápsula como un halo claro alrededor de las células (1, 3) (Figura 4). La tinción de la cápsula consiste en frotar una muestra bacteriana en una mancha ácida en un portaobjetos del microscopio. A diferencia de la tinción de Gram, el frotis bacteriano no se fija térmicamente durante una mancha de cápsula. La fijación de calor puede interrumpir o deshidratar la cápsula, lo que provoca falsos negativos (5). Además, la fijación de calor puede encoger las células, lo que resulta en un claro alrededor de la célula que se puede confundir como una cápsula, lo que conduce a falsos positivos (3). La mancha ácida colorea el fondo de la diapositiva; mientras que el seguimiento con una mancha básica, Crystal Violet, colorea las propias células bacterianas, dejando la cápsula sin mancha y apareciendo como un halo claro entre las células y el fondo de la diapositiva (Figura 5). Tradicionalmente, la tinta de la India se ha utilizado como la mancha ácida porque estas partículas no pueden penetrar en la cápsula. Por lo tanto, ni la cápsula ni la célula están manchadas por tinta de la India; en su lugar, el fondo está manchado. Congo Red, Nigrosin, o Eosin se pueden utilizar en lugar de tinta de la India. La tinción de cápsulas puede ayudar a los médicos a diagnosticar infecciones bacterianas cuando examinan los cultivos a partir de muestras de pacientes y guían el tratamiento adecuado del paciente. Las enfermedades comunes causadas por bacterias encapsuladas incluyen neumonía, meningitis y salmonelosis.

Figura 4: Esquema del protocolo de tinción de cápsula. El panel superior muestra el frotis de diapositivas antes de cualquier aplicación de manchas. El panel central muestra cómo el deslizamiento y las bacterias se ven después de la mancha primaria, Congo Red. El panel final muestra cómo la diapositiva y las bacterias se ven después de la contramancha, Crystal Violet.

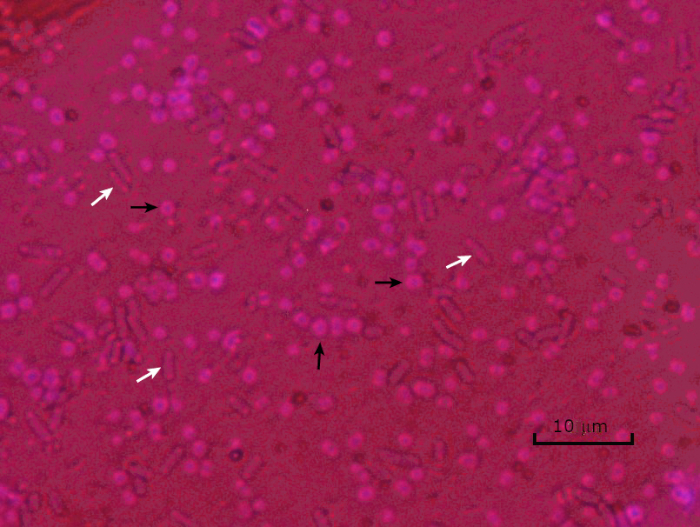

Figura 5: Resultados de la tinción de la cápsula. Tinción de cápsulas de Acinetobacter baumannii encapsulado (denotado con flechas negras) y Escherichia coli no encapsulado (denotado con flechas blancas). Observe que el fondo es oscuro y a. las células baumannii están teñidas de púrpura. La cápsula alrededor de las células de A. baumannii es evidente como un halo, mientras que E. coli no tiene halo.

En condiciones adversas (por ejemplo, limitación de nutrientes, temperaturas extremas o deshidratación), algunas bacterias producen endosporas, estructuras metabólicamente inactivas que son resistentes al daño físico y químico (1, 2, 8, 9). Las endosporas permiten que la bacteria sobreviva a las duras condiciones protegiendo el material genético de las células; una vez que las condiciones son favorables para el crecimiento, las esporas germinan, y el crecimiento bacteriano continúa. Las endosporas son difíciles de manchar con técnicas de tinción estándar porque son impermeables a los colorantes que se suelen utilizar para la tinción (1, 9). La técnica utilizada rutinariamente para manchar las endosporas es el Método Schaeffer-Fulton (Figura 6),que utiliza la mancha primaria Malachite Green, una mancha soluble en agua que se une relativamente débilmente al material celular, y el calor, para permitir que la mancha se rompa a través de la corteza de la espora (Figura 7). Estos pasos colorean las células en crecimiento (llamadas células vegetativas en el contexto de la biología de la endospora), así como las endosporas y cualquier espora libre (aquellas que ya no están dentro de la envoltura de células anteriores). Las células vegetativas se lavan con agua para eliminar Malaquías Verde; los endospores retienen la mancha debido a la calefacción del verde malaquita dentro de las esporas. Finalmente, las células vegetativas se contratratan con Safranin para visualizar (Figura 8). La tinción de endosporas ayuda a diferenciar las bacterias en ex años de esporas y los años no esporas, así como determina si las esporas están presentes en una muestra que, si está presente, podría conducir a contaminación bacteriana tras la germinación.

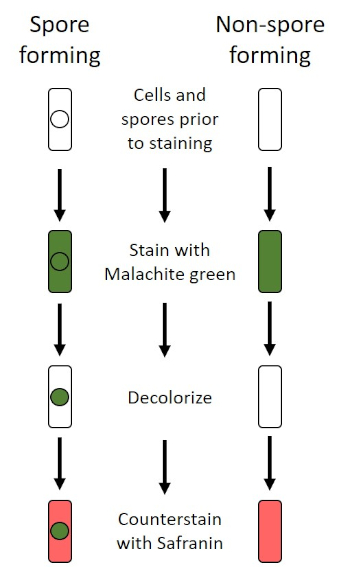

Figura 6: Esquema del Protocolo de Tinción de Endospora. La columna izquierda muestra cómo reaccionan las bacterias formadoras de esporas en cada paso del protocolo. La columna derecha muestra cómo reaccionan las bacterias que no forman esporas.

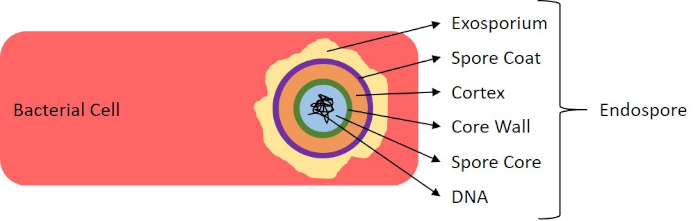

Figura 7: Diagrama de la estructura de la endospora. Célula bacteriana que contiene una endospora con las diversas estructuras de esporas etiquetadas.

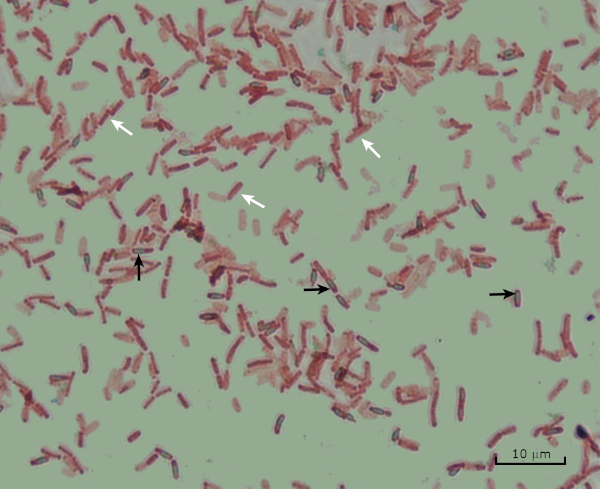

Figura 8: Resultados de la tinción de endospora. Una tinción típica de endosporas de Bacillus subtilis. Las células vegetativas (denotadas con las flechas blancas) están teñidas de rojo, mientras que las endosporas (denotadas con las flechas negras) están teñidas de verde.

Procedure

Applications and Summary

Bacteria have distinguishing characteristics that can aid in their identification. Some of these characteristics can be observed by staining and light microscopy. Three staining techniques useful for observing these characteristics are Gram staining, Capsule staining, and Endospore staining. Each technique identifies different characteristics of bacteria and can be used to help physicians recommend treatments for patients, identify potential contaminants in samples or food products, and verify sample sterility.

References

- Black, J. G. Microbiology Principles and Explorations, 4th edition. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (1999)

- Madigan, M. T. and J. M. Martinko. Brock Biology of Microorganisms, 11th edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. (2006).

- Leboffe, M. J., and B. E. Pierce. A Photographic Atlas for the Microbiology Laboratory, 2nd ed. Morton Publishing Company, Englewood, Colorado. (1996).

- Smith, A. C. and M. A. Hussey. Gram stain protocols. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.2886. (2005).

- Hughes, R. B. and A. C. Smith. Capsule Stain Protocols Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3041. (2007).

- Anthony, E. E. Jr. A note on capsule staining. Science 73(1890):319-320 (1931).

- Finegold, S. M., W. J. Martin, and E. G. Scott. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology, 5th edition. The C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Missouri. (1978).

- Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. (1994).

- Hussey, M. A. and A. Zayaitz. Endospore Stain Protocol. Laboratory Protocols. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. Available from: http://www.asmscience.org/content/education/protocol/protocol.3112. (2007).

Transcript

Bacteria are microscopic living organisms that have many distinguishing characteristics such as shape, arrangement of cells, whether or not they produce capsules, and if they form spores. These features can all be visualized by staining and aid in the identification and classification of different bacterial species.

To examine the first two characteristics of cell shape and arrangement, we can use a simple technique called Gram staining. Here, crystal violet is applied to bacteria, which have been heat-fixed onto a slide. Next, Gram’s iodine solution is added to the slide, resulting in the formation of an insoluble complex between the crystal violet and the Gram’s iodine solution. A decolorizer is then applied and any bacteria with a thick peptidoglycan layer will stain purple, as this layer is not easily penetrated by the decolorizer. These bacteria are referred to as Gram-positive.

Gram-negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan layer and will de-stain the decolorizer, losing the purple color. However, they will stain reddish-pink when a safranin counterstain is added, which binds to a lipopolysaccharide layer on their outside. Once stained, the cells can be observed for morphology, size, and arrangement, such as in chains or clusters, which further aids in classification and identification.

Another useful technique in the microbiologist’s toolkit is the capsule stain, used to visualize external capsules that surround some types of bacterial cells. Due to the capsule’s non-ionic composition and tendency to repel stains, simple staining methods won’t work. Instead, a negative staining technique is used, which first stains the background with an acidic colorant, such as Congo red, before the bacterial cells are stained with crystal violet. This leaves any capsule present as a clear halo around the cells.

The final major staining technique covered here can help determine if the bacteria being studied forms spores. In adverse conditions, some bacteria produce endospores, dormant, tough, non-reproductive structures whose primary function is to ensure the survival of bacteria through periods of environmental stress, like extreme temperatures or dehydration. However, not all bacterial species make endospores, and they are difficult to stain with standard techniques because they are impermeable to many dyes. The Schaeffer-Fulton method uses malachite green stain, which is applied to the bacteria fixed to a slide. The slide is then washed with water before being counterstained with Safranin. Vegetative cells will appear pinkish-red, while any endospores present will appear green. In this video, you will learn how to perform these common bacterial staining techniques and then examine the staining samples using light microscopy.

To begin the procedure, tie back long hair and put on the appropriate personal protective equipment, including a lab coat and gloves.

Then, clean a fresh microscope slide with a laboratory wipe. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X phosphate-buffered saline onto the first slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacterial colony in the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry.

Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Using tongs, pass the slide through the burner flame several times, with the bacteria side up, taking care not to hold the slide in the flame too long, which may distort the cells.

Now, working over the sink, hold the slide level and apply several drops of Gram’s crystal violet to completely cover the bacterial smear and then place the slide onto the bench to stand for 45 seconds. Next, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacterial smear directly. Now, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s iodine solution to completely cover the stained bacteria and then allow it to stand for another 45 seconds. Next, carefully rinse the iodine from the slide, as shown previously. While holding the slide at an angle, add a few drops of Gram’s decolorizer to the slide, allowing it to run down over the stained bacteria, just until the run-off is clear, for approximately 5 seconds. Immediately, rinse with water as shown previously. This will limit over-decolorizing the smear. Next, holding the slide level again, apply Gram’s safranin counterstain to completely cover the stained bacteria. After 45 seconds, gently rinse the Safranin from the slide with water, as shown previously, and then blot dry with paper towels.

Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective lens.

To begin this staining protocol, first put on the correct personal protective equipment and then ensure that the glass slides that will be used are clean.

Next, prepare the solutions. To make 1% crystal violet solution, mix 0.25 grams of crystal violet powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Then, prepare 1% Congo red solution by mixing 0.25 grams of Congo red powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water and vortex until dissolved. Now, pipette 10 microliters of the Congo red solution onto the slide. Using a clean, sterile pipette tip, select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Then, smear the bacterial colony into the dye to produce a thin, even layer. Completely air dry the bacterial slide for 5-7 minutes. Once the slide is dry, flood the smear with enough 1% crystal violet to cover the smear and let it sit for 1 minute. Now, hold the slide at an angle and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide, taking care not to squirt the bacteria directly. Continue holding the slide at a 45-degree angle until completely air-dried. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide using a light microscope with a 100X oil objective.

To perform endospore staining, first, prepare a 0.5% malachite green solution by mixing 0. 125 grams of malachite green powder with 25 milliliters of distilled water, and then vortex the solution until dissolved. Next, pipette 10 microliters of 1X PBS onto the center of the slide. Then, use a sterile pipette tip to select a single bacterial colony from the LB agar plate. Smear the bacteria into the liquid to produce a thin, even layer. Now, set the slide on the benchtop, and allow it to fully air dry. Once dried, light a Bunsen burner to heat-fix the bacteria. Pass the slide through the blue burner flame several times, with the bacteria side facing up. Then, once the slide has cooled, place a piece of precut lens paper over the heat-fixed smear. Next, turn on a hotplate to the highest setting, and bring a beaker of water to a boil.

Saturate the lens paper with the malachite green solution and, using tongs, place the slide on top of the beaker of boiling water to steam for 5 minutes. Keep the lens paper moist by adding more dye, one drop at a time, as needed. Next, again using tongs, pick up the slide from the beaker and remove and discard the lens paper. Allow the slide to cool for 2 minutes. Working over the sink, hold the slide at an angle, and gently squirt a stream of water onto the top of the slide. Now, hold the slide level and apply Safranin to completely cover the slide. Then, allow it to stand for 1 minute. Next, hold the slide at an angle and rinse as previously shown. Allow the slide to air dry on the benchtop. Finally, add a drop of immersion oil directly to the slide, and then examine the slide with a light microscope, with a 100X oil objective.

In the Gram staining protocol, two different colored stains can result. Dark purple staining indicates that the bacteria are Gram-positive and that they have retained the crystal violet stain. In contrast, reddish-pink staining is a characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria, which instead will be colored by the Safranin counterstain. Additionally, different shapes and arrangements of bacteria can be visualized after Gram staining. For example, it is possible to differentiate Cocci, or round bacteria, from rod-shaped Bacillus, or identify bacteria, which forms strands, compared to those which typically aggregate as clumps or occur singly.

In a capsule stained microscope image, the bacterial cells will typically be stained purple, and the background of the slide should be darkly stained. Against this dark background, the capsules of the bacteria, if present, will appear as a clear halo around the cells.

Lastly, in endospore staining, Vegetative cells will be stained red by the Safranin counterstain. If endospores are present in the sample, these will retain the malachite green stain and appear bluish-green in color.